From 2007 to 2012, Chapel Hill police saw 37 reports of sexual assaults or attempted sexual assaults — and only 13 arrests.

Sexual assault is defined as any form of sexual activity that the victim does not agree to, and can include inappropriate touching, rape and attempted rape.

North Carolina law further separates rape into two categories — first and second degree.

First-degree rape involves forced intercourse and the use of a deadly or dangerous weapon, or with children under the age of 13.

Second-degree rape involves forced intercourse with someone who is mentally incapacitated or helpless.

Of the 37 reported sexual assaults, 29 were classified as rape or forcible rape. Three were classified as attempted rape, four were classified as sexual assault and one as sexual battery.

An additional 22 reports were labeled as information, the classification often used when a report is made blindly to police.

A blind reporting option allows victims to describe the incident to police, but does not require them to attach their name or pursue an investigation.

“Blind reporting is really important,” Heafner said. “It does give a patient time if they want to pursue an investigation, and it lets our law enforcement know what’s going on in our community.”

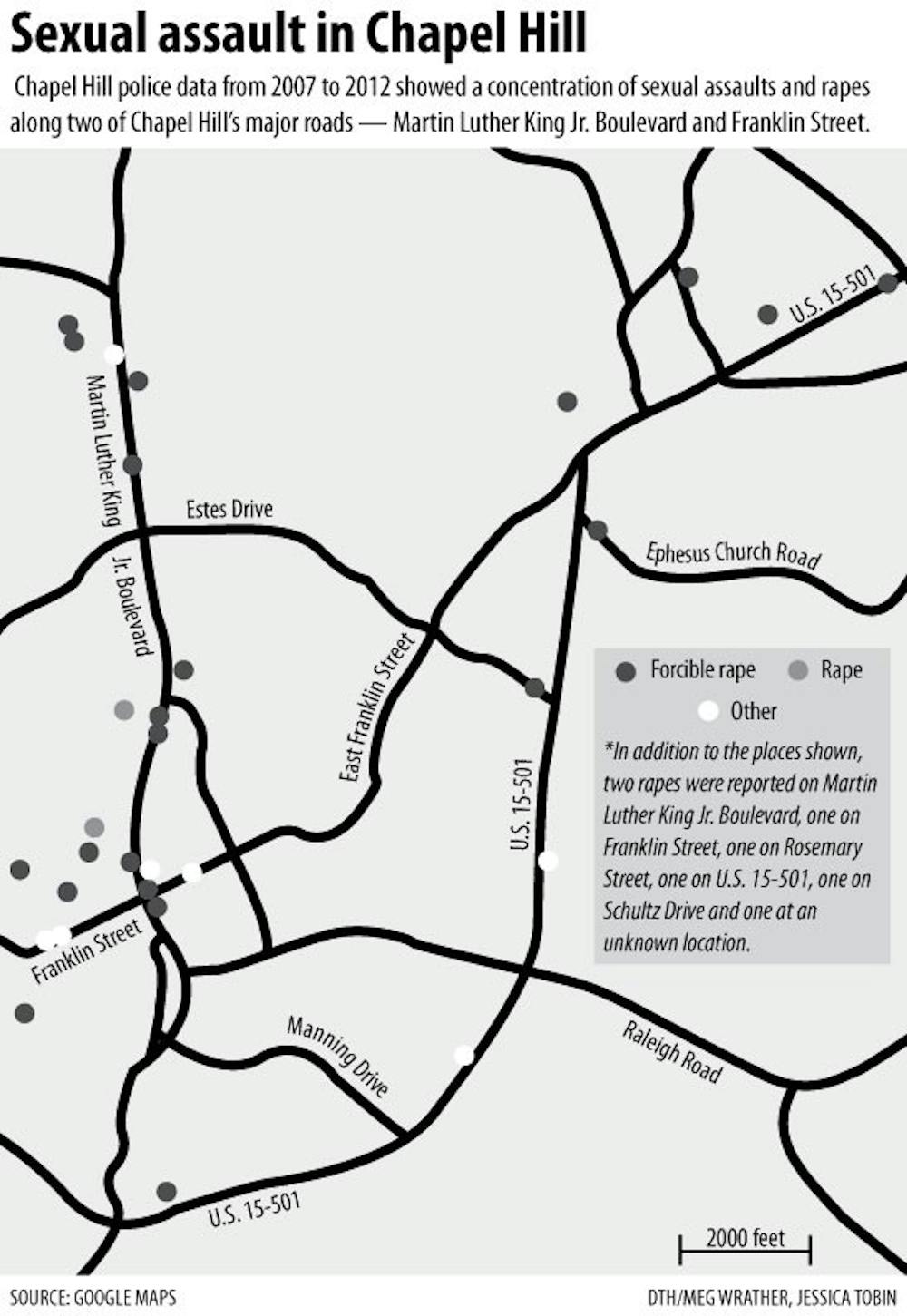

Chapel Hill police reports show a concentration of sexual assaults chiefly along Franklin Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard — two of the town’s most heavily trafficked roads.

Fourteen reported rapes or sexual assaults occurred on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard or a nearby street.

Twelve reports occurred on or near Franklin Street.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Garcia, who coordinates the crisis response team for the police department, said offenders may look to areas with high traffic and a high proportion of students, or for individuals with more social networking capabilities that would make them more available.

“Offenders look for vulnerability and accessibility,” she said. “When you look at certain populations, it’s the lifestyle factor.”

Garcia said analyzing the composition of areas where sexual assaults take place can help explain why they are highly concentrated.

Many large student housing developments are located along Franklin Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, where students and other local residents often walk to or from home and campus.

“We can try to be in control of the things we can be in control of,” she said. “We have to be more mindful in that we can reduce access points, and reduce vulnerability.”

Close relationships

Shamecca Bryant, executive director of the Orange County Rape Crisis Center, said her agency has seen a drastic increase in clients this year and expects to see 550 before the end of the fiscal year, compared to 458 last year.

She said about 25 percent of the center’s clients are between the ages of 18 and 29, and 25 percent are between 30 and 34.

Bryant said while this increase in clients doesn’t necessarily indicate a drastic increase in sexual assaults, the center has seen victims seeking services more frequently and, often, repeatedly.

She said the majority of sexual assault victims know their attackers, which can complicate whether they report to police and how they navigate the healing process.

“I think there’s still a large stigma around sexual assault,” she said. “It’s one of the few crimes were people question if they did something wrong to have that experience, that there was something they did that led to the assault.”

Hull said 73 percent of sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows. She said among minors, that number jumps to 93 percent.

“The nature of these relationships can be a barrier to disclosing,” she said. “That’s why it’s so important to report these incidents to the police.”

Garcia said she also often sees victims of sexual assault blame themselves.

“If you know someone, you can coerce or control them into doing something,” she said. “You don’t want to blame someone who you trusted.”

Heafner said this self-blame can be more prevalent when alcohol is involved — often a factor with incidents involving University students.

According to Chapel Hill police data, 39 percent of sexual assaults since 2007 involved the use of alcohol or drugs. Police records do not indicate whether the victim or offender was using the substance.

“I think it’s a matter of being judged because of where you were or because you might have been drinking,” Heafner said.

*Assaults on minors *

According to Chapel Hill police records, about 35 percent of the sexual assaults in Chapel Hill since 2007 involved minors.

Based on state law, the age of consent for sexual activity is 16.

Hospital employees, community groups and individuals are legally required to report sexual assaults when there is suspected child abuse or neglect by a parent or caretaker, or abuse or exploitation of a disabled or elderly adult by a caretaker.

Garcia said she thinks the number of incidents involving minors might be even higher than police can track, since many minors are hesitant to come forward to report sexual assault.

When minors are involved, she said it’s often difficult for the child to distinguish between what is acceptable and what is sexual assault, complicating the process.

“When dealing with the juvenile population, it’s difficult for them to assess when they’re being violated until it gets to the point when it’s extreme and frightening,” she said.

Heafner said in the past three weeks, UNC Hospitals has seen an uptick in sexual assault patients, many of whom have been children.

“We’ve had a patient a day, and a lot children,” she said.

Treatment and stereotypes

Heafner said treating sexual assault victims can be complex and difficult, but it’s important for treatment providers to put the needs of the patient first.

“Our biggest thing is we provide options for care,” she said. “It takes a lot of courage for these individuals to come forward.”

She said the option for data collection, to report the assault to police or to pursue STD treatment falls on the patient.

“It’s important for us that we inform them what their options are,” Heafner said. “This is a crucial process in their healing and to take back their power, because after being sexually assaulted you see a lack of control.”

Garcia said her police team is has also been specifically trained to respond to sexual assault victims and make them feel comfortable when reporting to the department.

“We’re just grateful that people trust us enough to come forward and report it,” she said.

“They want to know where the report goes, who has access to it, will they have input. We don’t want to mimic behaviors of the offender by taking control away from people.”

Sexual assault victims are three times more likely to suffer from depression and 26 times more likely to abuse drugs, based on a 2002 World Health Organization study.

Laurie Graham, programs director for the Orange County Rape Crisis Center, said the center offers free counseling, a hotline and companion services for victims so they can have someone to accompany them to the police department or to the hospital.

“We do know that experiencing trauma can have long lasting effects,” she said. “It can take a very long time to heal from.”

Garcia stressed the importance of inter-agency cooperation when handling sexual assaults.

“It’s very much a community issue, a national issue and a world issue,” she said. “There’s a whole bunch of agencies bettering our system’s response. It’s much larger than one agency.”

Contact the City Editor at city@dailytarheel.com.