In the last decade, college prices have increased at a higher rate than the prices of other goods and services, according to a report by the College Board

Tuition and fees for in-state students at public colleges increased at an average rate of 5.6 percent per year beyond the rate of general inflation from 2001-02 to 2011-12 — compared to 4.5 percent per year in the 1980s and 3.2 percent per year in the 1990s.

The most recent tuition and fee hikes at public colleges exceed those at private institutions, where rates increased at an average rate of 2.6 percent per year beyond inflation from 2001-02 to 2011-12.

Increased costs have coincided with a similar uptick in the amount of financial aid allotted to students, as both grant aid and federal loans per full-time undergraduate student have increased at an average rate of about 5 percent per year from 2000-01 to 2010-11.

The nature of the relationship between those two trends — rising college costs and increasing financial aid awards — has been a topic of considerable debate.

The cost debate

While costs at both public and private institutions continue to rise, two competing explanations have been offered about the driver of those costs.

Administrators nationwide frequently cite the severity of state budget cuts since the 2008 financial crisis in their decisions to raise tuition and fees.

State funding per full-time student declined by 18 percent from 2007-08 to 2010-11 — the largest three-year decline in 30 years of data reported by the College Board.

The UNC system has absorbed its own spate of state funding cuts in recent years, including a cut of $414 million, or 15.6 percent, last year that prompted universities to eliminate about 3,000 filled positions and hundreds of course sections. The system’s Board of Governors responded by approving an average systemwide tuition and fee increase of 8.8 percent in February.

Other higher education analysts refute the notion that cuts at the state level have spurred escalating costs. They say that though state revenues decline during recessions, states typically restore funding over time once the economy improves.

Between 1987 and 2009, per capita state spending on higher education increased by 31 percent after adjusting for inflation. North Carolina, which is known for its generous funding of higher education, increased its per capita spending on its public universities by an inflation-adjusted 5.2 percent between 1990-91 and 2010-11.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Enrollment typically spikes during periods of high unemployment — such as in the recent recession — as students seek to become more competitive in the job market.

Neal McCluskey, associate director of the Center for Educational Freedom at the Cato Institute, a libertarian-leaning think tank in Washington, D.C., said colleges often overreact to not receiving a boost in state funding in times of increased enrollment.

“Public colleges and universities raise their tuition — or the revenue, at least, that they generate through tuition on a per-pupil basis — at a much bigger proportion than the money they lose … as a result of state and local cuts,” he said.

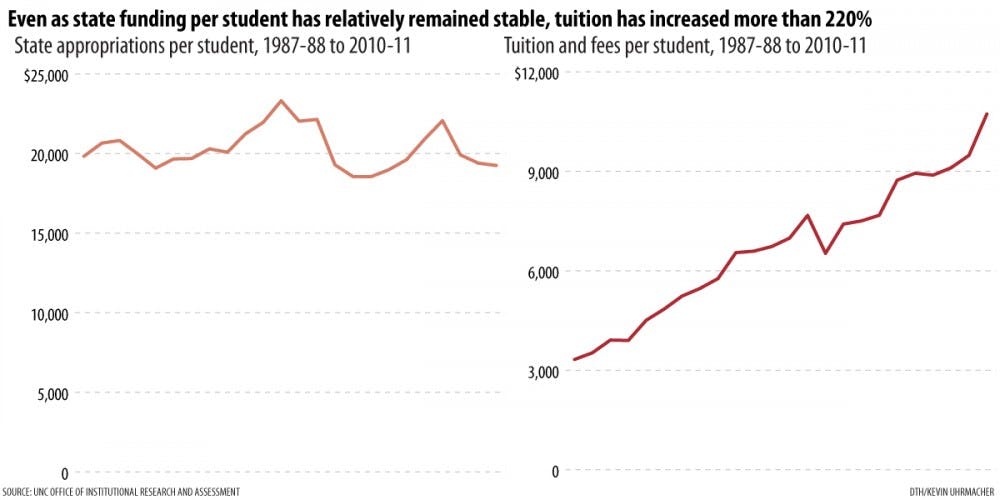

State money per full-time student at UNC-CH decreased by 2.9 percent between 1987-88 and 2010-11. During that same span, the tuition and fee revenue collected per student increased by a much higher percentage — 222.6 percent.

State funding per student has seen a slight decrease, but tuition revenue collected from students has increased at a much higher percentage.

What’s to blame for this disproportionate increase? More federal financial aid funding, McCluskey said.

The financial aid bubble

With tuition rates spiraling upward, more and more students have sought student loans to cover the cost of higher education. Student debt from loans surpassed $1 trillion this year — exceeding the amount of credit card debt among young adults.

Recipients of need-based aid such as Pell Grants, which composed 70 percent of federal grant aid during the decade from 2000-01 to 2010-11, have also swelled.

The number of students receiving Pell Grants more than doubled from 3.9 million, or 20 percent of undergraduates, in 2000-01 to 9.1 million, or 35 percent of undergraduates, in 2010-11.

Much of the recent aid, which includes tuition tax credits and the expansion of eligibility for Pell Grants, has been targeted toward middle-class students.

Savings from tax credits for taxpayers with incomes below $25,000 increased from 5 percent in 2008 to 17 percent in 2009, while savings for those with incomes above $100,000 increased from 18 percent in 2008 to 26 percent in 2009.

The percentage of Pell Grant recipients from families with incomes of at least $50,000 increased from 3.7 percent in 2007-08 to 7.5 percent in 2010-11.

Yet middle-class students are often the ones saddled with the most debt.

At 12 out of 16 UNC-system schools in 2009-10, the in-state graduating seniors with the highest debt levels — an average amount of $19,797 — came from families with incomes of more than $75,000.

And eight of those schools increased tuition and fees by a higher percentage than the system average between 2006-07 and 2010-11.

Elizabeth City State University, which increased tuition rates by 47.9 percent during that period — tied with Western Carolina University for the most among the 16 universities — also had the highest percentage of in-state undergraduate Pell Grant recipients in the system in 2009.

McCluskey said it’s no mistake that the schools with the highest levels of aid recipients also have the highest costs.

Though colleges might not specifically consider increases in federal aid when setting costs, increased demand from students who can now afford college impels administrators to provide more services and improve the quality of their institutions, he said.

But students aren’t paying the full price for what they demand, he said, mostly because the growing financial aid bubble prevents them from doing so.

“The only reason the price can go up every year is because somebody can pay it,” he said. “Somebody can pay it because they’re doing it with other people’s money.”

Non-profit colleges simply spend any money they receive that exceeds the costs of education, McCluskey added, meaning that spending for one year is equivalent to revenue collected the next.

This structure has prevented many schools from operating more efficiently, he said.

Revenues have exceeded expenses at UNC-CH in 23 out of the last 25 years at an average of $42.3 million.

Despite that surplus, the percentage of the University’s expenses devoted to academics decreased from 39.4 percent to 32.3 percent during that time period — while administrative expenses decreased only slightly, from 3.9 percent to 3.7 percent.

Baby and the bathwater

But administrators say the availability of financial aid rarely factors into their decisions to raise prices.

Jon Young, provost at Fayetteville State University, said the university primarily focuses on offsetting losses in state money, not taking advantage of higher aid levels.

“It’s not really been a factor here,” Young said. “Some institutions might look at that. I wouldn’t rule out that possibility.”

Deborah Tollefson, director of financial aid at UNC-Greensboro, said she’s worried that efforts to efficiently allocate financial aid might inadvertently punish the neediest students.

“We just need to make sure that we don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater as we try to ensure there’s less fraud and abuse of financial aid programs, because they are costly domestic spending programs,” she said. “We also need to make sure that we make those funds available to the people that need them the most.”

UNC-CH Chancellor Holden Thorp said the UNC system’s historically low tuition rates suggest there hasn’t been much influence of federal financial aid on rising costs. In the 2010-11 academic year, all 16 system schools ranked in the bottom four of their peers for undergraduate tuition and fee rates.

“For the places that have diversified funding sources like we do, it’s kind of hard to say any one source is driving up the cost,” Thorp said.

Reforms unlikely

No matter the source of the rising cost of higher education, reforms that might affect it at the federal level are unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., and Mitt Romney’s vice presidential running mate, introduced several reforms in his budget proposal earlier this year.

Ryan, an advocate of shrinking the financial aid bubble and limiting eligibility to the most needy, proposed introducing an income cap and maintaining the maximum award level of $5,550 for Pell Grants recipients — while Obama’s budget would raise the maximum award to $5,635 for 2013-14.

Ryan’s budget cites the U.S. Department of Education’s warning earlier this year that the Pell Grant program could have a shortfall of $20.4 billion if actions aren’t taken to reduce the program’s costs.

His proposal, which passed the U.S. House of Representatives but was rejected in the Democratic-led Senate, would have also eliminated the subsidy on some federal loans and raised the interest rate back up to 6.8 percent. But he later voted to extend the 3.4 percent rate.

In Obama’s campaign to maintain the lower interest rate , the president stressed that the higher rate would translate into an average of $1,000 in additional debt for more than 7 million students nationwide.

Along with the presidential candidates, most members of Congress have also turned their attention to this fall’s election — and away from education funding, said Ballou, the UNC-system lobbyist.

“Trying to push something like (financial aid reform) through Congress during an election year would be contentious and difficult to do,” he said.

Contact the desk editor at state@dailytarheel.com.