In a divisional matchup with the Philadelphia Eagles on Sept. 30, 1984, Rick Donnalley, a third-round draft pick out of UNC, snapped the ball to Washington Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann and rushed to chop a linebacker.

As Donnalley attempted to block his opponent’s legs, the linebacker lifted his thigh into Donnalley’s head. The next thing Donnalley remembers is waking up on the ground at RFK Stadium, his teammates standing over him waiting for the next play to start.

“The guys were yelling at me, ‘Get the huddle set!’” he said. “I was a little disoriented.”

Donnalley blacked out for 10 seconds after taking a blow to the head but didn’t miss a single play in the Redskins 20-0 win against the Eagles that day. At that time, situations like his weren’t out of the ordinary.

“You never really heard the word ‘concussions.’ It was always, ‘You got your bell rung,’” Huff said.

During the past two decades, that mentality has begun to shift.

With the help of research from Guskiewicz, evidence-based guidelines for return-to-play started popping up in college and professional football.

Research has shown that most concussions in football occur on special teams plays. So, prior to the 2011 season, the NFL moved the spot of kickoffs from the 30-yard line to the 35-yard line. There was a 43 percent decrease from 2010 in concussions sustained by NFL players.

Guskiewicz, hopeful for a similar decline in diagnosed concussions in college football, advised the NCAA to adjust its kickoff rules as well. Before the start of this season, the kickoff was moved up five yards, limiting players to a 5-yard running start.

In April 2010, the NCAA held a concussions summit, at which experts, including Guskiewicz, met at the NCAA’s Indianapolis headquarters to discuss safety measures needed to avoid head injuries.

It was then that the NCAA made a blanket rule that required an athlete with concussion symptoms to be evaluated by a physician before returning to his or her sport.

Jeffrey Anderson, chairman of the NCAA’s committee on competitive safeguards, said the legislation has brought much-needed consistency to the organization’s policies. Still, as research on concussions continues, the committee’s role in protecting college athletes evolves.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“It’s a moving target,” Anderson said, “because there’s still so much about concussions that we don’t know.”

On the cutting edge

Dressed in a dark blue jersey and sitting on a gurney inside the athletic training room at Navy Fields, a UNC football player looks inquisitively at the large, antenna-like apparatus athletic trainer Jackie Harpham is setting up in the corner of the room.

“Is there lightning coming?” he asks.

The UNC football players might not know exactly what the Head Impact Telemetry system does. But one day, it might save their lives.

Underneath the interlocking N.C. on 60 North Carolina helmets lie six sensors the size of nickels. These sensors measure the force and location of hits the wearers sustain and communicate the data by radio frequency to a computer on the sideline.

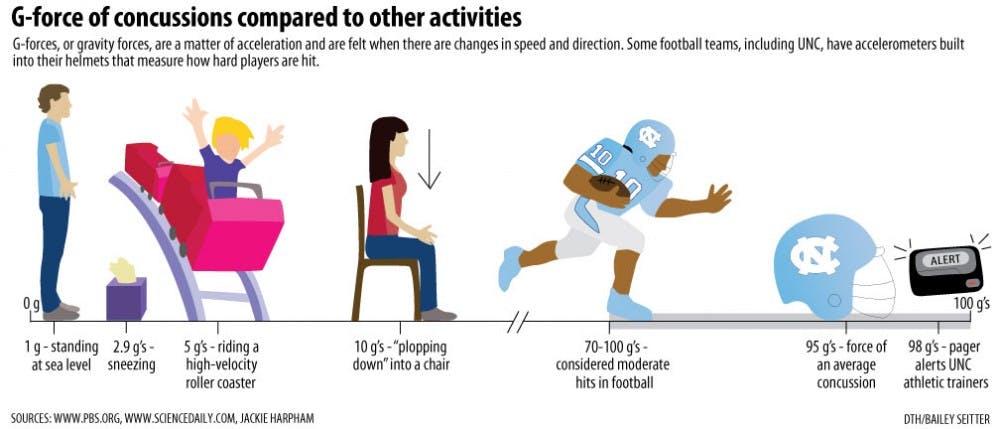

A hit of less than 20g’s is negligible and can occur when a player gets bumped or drops his helmet on the turf. Hits of between 70-100g’s are considered moderate. If the sensor records a hit of greater than 98g’s, a pager worn by a UNC athletic trainer will go off.

Since UNC began using the HIT system in 2004 after it secured a grant from the Centers for Disease Control, the data have been saved for longitudinal studies. The technology, which is used by just a handful of colleges and universities nationwide, helps guide the NCAA and NFL in making rules changes.

That is the kind of concrete data on which Guskiewicz has based his livelihood.

As an athletic trainer for the Pittsburgh Steelers while in graduate school, Guskiewicz was perplexed by the subjective way in which athletes would return to play after sustaining concussions. So 20 years ago, as a doctoral student at the University of Virginia, he began research on the subject to change that.

“Anecdotally we think, ‘Wow, that looks dangerous. They hit their head a lot,’” Guskiewicz said about the three-point stance. “My argument has always been, ‘Let’s let science guide us. Let’s really answer that question.”

At the time, Guskiewicz said, tests to evaluate concussions either were not sophisticated enough to properly detect the injuries or were too complicated and time-consuming to be widely used.

Guskiewicz later developed the first set of “user friendly” balance and cognitive tests, and over the years, introduced them to doctors and trainers.

It’s largely due to his dedication to the study of concussions that evidence-based return-to-play guidelines have become widespread.

For Fedora, Guskiewicz’s knowledge, coupled with the HIT system, not only keeps his players safe but takes some of the guesswork out of diagnosing their conditions.

“A kid might have the kind of symptoms where in the past you’d say, ‘Hey, he probably has a concussion, he’s out for a week,’” Fedora said. “Now, you can rule those things out because of the data he’s put together.”

Shortly after Fedora was hired in December 2011, he called Guskiewicz and asked him about concussions and the HIT system.

Fedora wanted to learn how it worked so that he had a better understanding of the tools that kept his players safer.

“(UNC football coaches) are very smart to have used that when they’re sitting in the living room of a top recruit,” Guskiewicz said, “to say, ‘We’re one of the few places in the country that has this technology, and it helps us protect our players.’”

The impact of impact

Huff vividly recalls the day three years ago when he picked up the telephone and a member of Guskiewicz’s research staff was on the line.

Just three weeks before, Huff, the third overall pick in the 1975 NFL draft, had gone through a series of cognitive tests at Guskiewicz’s Center for the Study of Retired Athletes.

Guskiewicz was beginning a study on the role of fish oil supplements in the slowing of brain deterioration. He used those initial cognitive tests to determine which subjects qualified for the study.

“When they called me back, it was kind of good news, bad news,” Huff said. “They said, ‘The good news is, you qualified for the test. The bad news is, you qualified for the test.’”

Huff and others who qualified for the study were given either fish oil supplements or a placebo. They underwent additional testing eight months later to track the results.

During his rookie season with the Baltimore Colts, Huff sustained the first of three documented concussions he had in his career.

After getting hit on a play, Huff had no idea where he was and even ran to the wrong sideline coming off the field. He returned to practice the next day. Later in his career, Huff spent the night in the hospital after being diagnosed with his third concussion.

Because of the inefficient protocol for diagnosing concussions during his time in the NFL, Huff thinks it’s possible he’s suffered at least a dozen more than the three documented cases.

Huff said he doesn’t currently experience noticeable challenges because of the head injuries he’s sustained, and Guskiewicz’s tests didn’t find any signs of the diseases some of his NFL peers battle daily as a result of trauma. For that, he feels extremely fortunate.

When he’s not managing his Chapel Hill-based home renovations company, Ken Huff Builders, Inc., Huff now serves as a retired player consultant at the Guskiewicz’s center.

Huff is well aware of the possibility of adverse effects that could occur later in life, but for now, he takes comfort in knowing that through Guskiewicz’s research, he’ll be able to spot any potential changes in his mental health right away.

“If there was an issue later in life,” Huff said, “there will be something to compare what’s happened to me to.”

A fuzzy future

After sustaining a goal line blow in a game against Wake Forest on Sept. 8, Renner walked in a straight line, touched his hand to his nose and recited the months backwards. When he passed these and other concussion tests, the quarterback returned to the game, winning dominating his thoughts.

Huff, who played in the 1984 Super Bowl, can certainly understand that win-at-all-costs mentality. But now, having a kind of insight that only experience can bring, he also knows the consequences that very mindset and undying love for the game of football can bring later in life.

“When you do forget something,” Huff said, “it does flash in your mind — is it age, or is it early onset dementia or Alzheimer’s?”

In what has been referred to as a “concussions crisis,” many have wondered what the future holds for the game of football and whether the potential for brain trauma associated with the sport will keep people from playing it.

Guskiewicz said the picture of concussed football players portrayed in the media lately is a lot more gruesome than the reality. Still, he concedes, he’s concerned about the wellbeing of 25 percent of the retired athletes that walk through the doors of his center.

For players who strap on helmets and run out of a tunnel to thousands of screaming fans every Saturday in the fall, the outlook for football shines. To some who have since moved on from that glory and now live with the very real possibility of impairment because of it, the future isn’t nearly as bright.

“Fifty years ago people thought it was healthy to smoke cigarettes, and then they figured out, ‘Oh, maybe it causes cancer,’” Donnalley said.

“Maybe 50 years from now, they’ll think, why did we ever play a sport like that? … They’ll look back at it and say, ‘Those people were crazy.’”

Contact the desk editor at sports@dailytarheel.com.