“While we don’t know if that is precisely the case, it certainly could be,” she said.

There has also been an increase in the number of students who do not report a race or ethnicity, said Ashley Memory, senior assistant director of undergraduate admissions.

This fall, 194 new first-years opted out of reporting their race — up from 87 in 2012.

Applicants versus admittance

The UNC Office of Undergraduate Admissions takes into account all student-reported races and ethnicities when determining the demographic breakdown of applicants and admitted students.

“We’ve been required to report separately those students who disclose more than one race or ethnicity,” Memory said, adding that admissions sorts data differently from the Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. “Our office counts all students who identify as African-American, even if they report multiple races.”

This method of reporting causes students who identify as belonging to more than one racial or ethnic background to be counted as a member of both groups, which could potentially skew the application and admittance numbers.

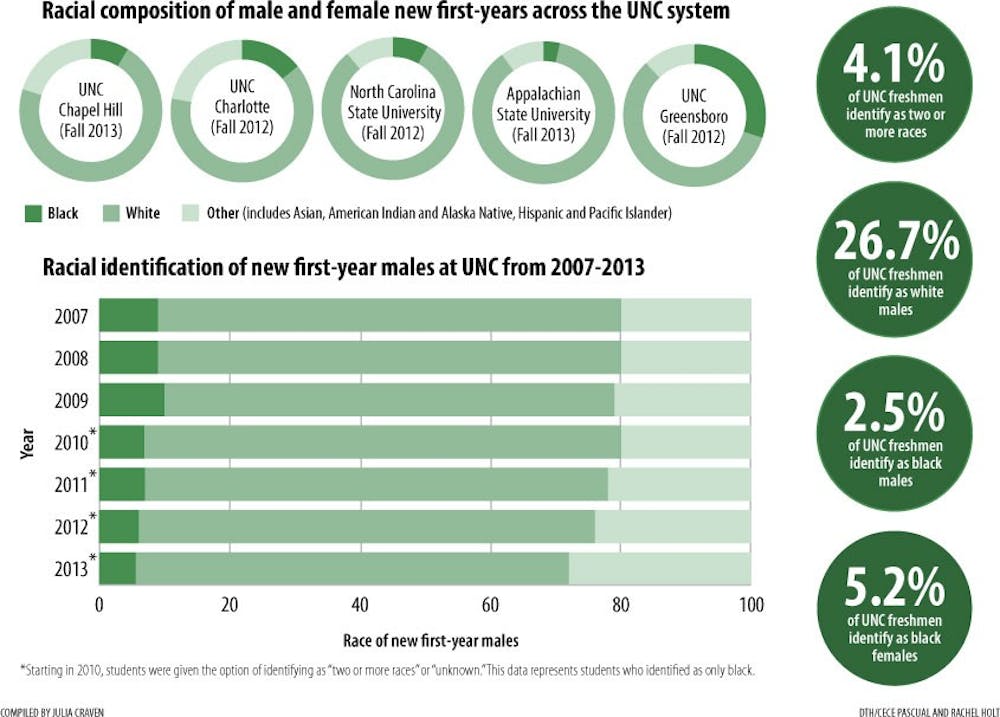

For the 2013-14 academic year, 1,136 males identifying as black — either fully or partially — applied to UNC out of 30,835 total applicants.

Of the 1,136, 245 gained admission — a number fairly aligned with UNC’s 27.6-percent overall acceptance rate.

But the UNC black undergraduate population is not representative of the state demographics.

Black men and women make up about 21 percent of North Carolina’s population compared to 8.5 percent of total UNC undergraduates who report being only black.

Deborah Stroman, chairwoman of the Carolina Black Caucus and an exercise and sports science professor, said this is concerning.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“The University is the university of the people,” she said. “We have an obligation as the flagship university to represent the people of the state.”

Memory said the low number of black males applying to college is a national issue, and it’s hard to speculate why this is happening.

She also said fewer young men in general, regardless of race, are applying to college, and they might not be attending in order to help support their families.

“It really depends on what the life goals are for these men,” Memory said.

Shakeel Harris, a junior at UNC who identifies as black, said getting black men to UNC starts in the home.

“If you’re not pushed as a child to do well and succeed educationally, you’ll lack the drive,” he said.

Harris also said white students are more likely to be pushed to do well educationally than blacks, giving them privilege over minority students.

UNC doesn’t have an official affirmative action policy, but personal attributes are considered when looking at applications — though they do not guarantee admission.

“We do seek qualities in the student that will help shape the incoming class,” Memory said. “(But) we only want to admit the strongest students of all ethnicities and colors.”

The UNC environment

Stroman said low black male enrollment is of crisis-level concern and UNC’s environment should be taken into consideration.

“Is (UNC) a welcoming community for young black men? Does it embrace their culture?” she said.

Darius Latham, president of UNC’s Black Student Movement, said the University has a fairly welcoming environment for black men.

“I don’t necessarily know if UNC, as an entire campus community, embraces Black culture,” he said in an email. “However, I’m confident that the UNC community is tolerant of its existence.”

But some believe UNC is not as diverse as advertised.

“We are diverse in certain aspects,” Harris said. “But, in terms of race, I’m not going to say we’re missing the mark completely, but there are strides that need to be made.”

Clayton said black males who are currently enrolled should be asked why they applied to UNC to get a sense of what could be done differently to help alleviate low applicant and enrollment numbers.

Latham made similar remarks to Clayton.

“I don’t know how many minority students were actually admitted to Carolina and simply decided not to enroll,” he said. “But it would be beneficial to the University (because of these low enrollment numbers) to reach out and see exactly what led students to enroll at other institutions.”

He also said minority students should speak up during class discussions.

“If you happen to be the only minority in a class, you should make more of an effort to be involved in classroom conversation — not because you’re a ‘race representative,’ but because your viewpoint and outlook on topics is just as valued,” he said.

Despite a low number of black males, freshman Garrett Holloway said he doesn’t feel out of place at UNC.

“I’ve been able to form some bonds with other African-American men here, and I think the fact that there aren’t a lot of black men here is what makes us closer,” he said.

Stroman said the black male voice benefits and enhances UNC’s academic environment.

“(Black men) bring about a greater richness in thought and action,” she said. “I would hate to have a university where the only young black men on this campus are athletes. That doesn’t help the athletic department. That doesn’t help the academic community.”

Student groups such as BSM make it a point to ensure the black voice remains present at UNC.

“(BSM) makes sure the Black voice does not get lost or undermined and that issues pertaining specifically to our community do not get pushed under the rug,” Latham said.

Minority outreach

The undergraduate admissions office holds recruitment events in the state and nationwide in an attempt to educate larger numbers of black men about the University.

“We’re just casting a wide net,” Memory said. “Students of any background, whether they’re born in North Carolina or not, can fit in at Carolina.”

The Provost’s Committee on Inclusive Excellence and Diversity is also assessing how students are connected with and informed about opportunities at UNC, Clayton said.

“We need to connect more authentically with those populations,” she said.

Minority outreach programs — such as Project Uplift and Tar Heel Target — aim to do just that.

These programs connect with communities and families, inform minority students and help them begin to see themselves at UNC, Clayton said.

Tar Heel Target sends minority student recruitment volunteers to their hometown high schools to meet with prospective students. Project Uplift invites about 1,000 rising high school seniors from historically underserved populations to spend two days experiencing the academic and social climate of UNC.

Carolina College Advising Corps, another outreach program, advises students on how to apply for college and reaches 18 percent of all black high school seniors statewide.

“We see excellence and diversity as inextricably linked,” Memory said.

“We don’t think we can have one without the other.”

university@dailytarheel.com