It was at that moment, McCain later said, that he vowed to never racially stereotype anyone.

He had gone into the sit-in expecting that he might be arrested, or even killed.

“He said that was a good reason to die, because if he couldn’t have the same privileges as everyone else, that wouldn’t work for him,” said Velma Speight-Buford, former chairwoman of N.C. A&T’s Board of Trustees and a close friend to McCain.

The number of people participating in the sit-in and ensuing demonstrations went from four to 1,000 in five days. Protests spread to 54 cities in nine states in eight weeks, said Duke University professor William Chafe, who wrote a book called Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom.

Many of the participants were students from N.C. A&T and the nearby private historically black college for women, Bennett College.

“They had no idea what an extraordinary catalyst this would be for a huge movement, but it was the spark that lit the fire,” Chafe said.

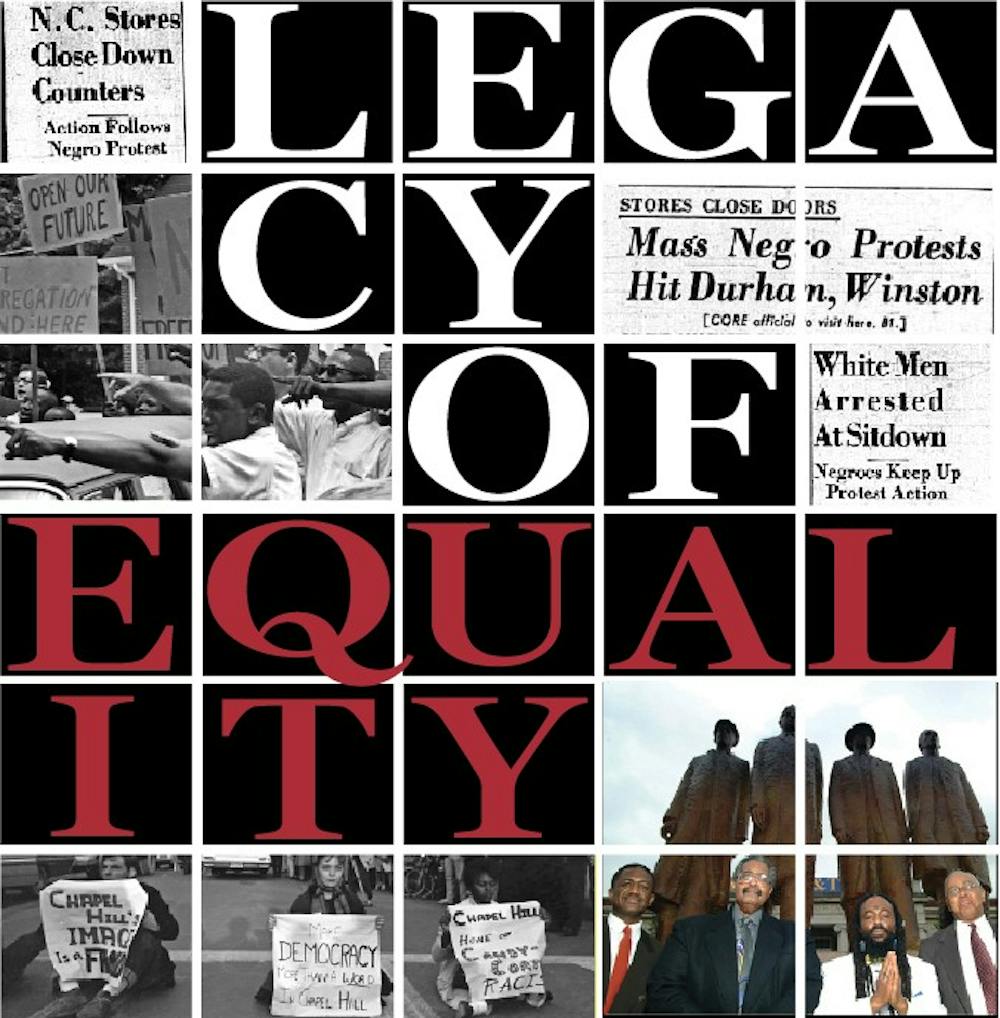

The movement also spread to Chapel Hill, where schools and restaurants were segregated.

“Those are the things that happened in Chapel Hill that a lot of people don’t talk about,” said the Rev. Robert Campbell. “We’ve not always been that compassionate blue heaven.”

Campbell, 11 years old at the time, remembers the hope that the status quo would soon change.

“If we could go in the store and buy a sandwich and eat it rather than go out in the hot sun — we were excited about that,” he said. “The pleasure of being able to sit where you once could not sit … it’s hard to explain the mood and the feeling, but it was a wonderful feeling.”

A life of service

McCain later married another participant in the Greensboro demonstrations, Bennett College alumna Bettye Davis, and they had three sons. She died last year.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

McCain worked in Charlotte for almost 35 years. He received an honorary doctorate from N.C. A&T in 1994, and never stopped speaking out against inequality. He received many awards for his service.

Speight-Buford, who had been friends with McCain for decades, remembers going with McCain to Atlanta for his induction into the National Black College Alumni Hall of Fame.

“Franklin and I sat in the lobby of the hotel in Atlanta, and then too, he said, ‘Why me?’” Speight-Buford said. “I had to remind him it was based on his courage.”

And in 2005, N.C. A&T built four dorms on the quad, each named after a member of the Greensboro Four.

“You would have thought we had named the Board of Governors for Franklin,” Speight-Buford said. “That’s how important it was to him.”

A passion for education

McCain served on the Board of Trustees at N.C. A&T from 2005 to 2009 and was named chairman in 2008. He also served on the boards at N.C. Central University and Bennett College. In 2009, he went to the UNC-system Board of Governors, where he stayed until last year.

“He spent an enormous amount of time on higher education,” said system President Tom Ross. “He cared about every student at every institution.”

In McCain’s midnight talks with Speight-Buford — phone calls that would start just before midnight and would stretch on until 1 or 2 a.m. — he’d tell her about his meetings with student body presidents about ongoing issues.

“I heard a couple of the SGA presidents say that he was always in their corner when it came to them getting a better education,” Speight-Buford said.

In 2012, the Board of Governors passed a hefty tuition increase for in-state undergraduates systemwide. Students protested at the board’s vote, and afterwards, all the board members left the room — except McCain. He stayed as the students took over the boardroom and chanted protests.

“I have an interest in what the students are interested in,” McCain told The Daily Tar Heel at the time. “Students have the opportunity to practice democracy. If you want to get noticed, you have to get a little louder. I think that’s acceptable.”

When his granddaughter, Taylor McCain — now a UNC-CH sophomore — left for college, he told her that she had to fight for what she believed in.

“He said, ‘no one is inferior to you. You have all of the capabilities everyone else has to excel,’” she said. “(He said), ‘If you sit around and wait, it’ll never get done — you have to do it yourself.’”

And every year, on Feb. 1, McCain would visit N.C. A&T and speak to the students, challenging them to face the issues of the day.

“We used to say that when Franklin spoke, it was like (students) were spell-bound,” Speight-Buford said. “Last year, the young man who introduced him said that tears rolled down his cheeks from the time Franklin spoke to the time he finished. When Franklin spoke, it was moving.”

A legacy of equality

There are now only two of the Greensboro Four left — Khazan and McNeil. Richmond died in 1990.

Their example of non-violent demonstration carries on to this day, Campbell said.

“Do what you do, but do it so you show love,” he said. “You have to be steady, you have to make a commitment, so when you’re confronted with violence, show love and you will overcome. And we still do that today.”

The Moral Monday movement, in which state citizens banded together in protest of some of the Republican-backed policies that passed the N.C. General Assembly, is an example of that, Campbell said.

Speight-Buford said McCain stayed abreast of current issues. He was concerned with the recently-passed voter ID law, as well as women’s rights, she said.

“That’s his legacy — not just the A&T Four, but his ongoing commitment to the fight for equality, for civil rights, for human rights,” Rubio said.

His granddaughter, Taylor, said that to her, McCain was simply her granddaddy — a kind, sweet man who loved her. Still, she remembers learning in elementary school how he had made history.

“For me, I had a standard that was set for me the day I was born,” she said. “Why couldn’t I do something just as great?”

state@dailytarheel.com