Mihalik’s staff outfitted each player with an xPatch — a chapstick-sized accelerometer that tucks hidden behind the right ear.

The purpose is simple: When players incur head impacts, the accelerometer measures those forces.

The patches monitor both rotational and linear acceleration. Rotational acceleration happens when the head turns or rotates following an impact, whereas linear acceleration occurs when the head moves suddenly in a particular direction.

With video assistance, the xPatch becomes even more useful. Researchers watch game tape alongside their hit data to determine who exactly got hit — and how hard — at different points in the game.

“You can be strong as an ox, but if you don’t see it coming, who cares?” Mihalik said.

“The ability to measure these things in real time, which is the key ... is just very, very, very difficult.”

It might be, but researchers and coaches believe the potential benefits are worth it.

That starts with the coach, a 22-time national champion in women’s soccer: Anson Dorrance.

Dorrance recognizes that data show his athletes are more easily concussed than their male counterparts, and he’s willing to try different experiments if they could help his team.

“I know there’s a colleague of mine in Denmark that is building a women’s soccer ball — and she is trying to introduce it in the leagues in Europe — that is a little bit lighter and maybe a tad smaller,” Dorrance said.

But Dorrance has another idea, and it revolves around Roy Baroff.

Baroff was one of Dorrance’s players early in his men’s coaching career, but the left defender had a quirk — he never used his head.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“Because he never headed the ball, he developed an incredible amount of skill because any ball that was played to him in the air, he didn’t head it,” Dorrance said. “He would back up and chest it.”

Brandi Chastain, formerly a defender for the United States women’s soccer team, has proposed a similar solution to reduce the potential for head injuries: eliminate heading in the youth game until the age of 14 and slowly work it in from then on.

Doing so would not only mean fewer head-to-head collisions going for balls in the air but also more awareness about the dangers of concussions.

Regardless of the solution, experts say there’s more that has to change than just policy.

Changing expectations

There’s a perception that every hit over the accelerometer-triggering 10 G might cause an injury.

“I think that that is inherently problematic in defining the precise threshold due to individual variability. I don’t think it’s going to end up being a one-size-fits-all kind of problem,” said Dr. Dan Kaufer, director of the UNC Memory Disorders Program.

“Some boxers can just sit there and take a punch and look like they’re not affected at all, and other people take the same punch and they’re down on their back — and it can be the same punch.”

The truth of the situation is that, like different eyes or fingerprints, every person has a unique brain.

But it’s another perception, too — that as long as the pain is manageable, playing is all right.

“What people really have to alter is the expectation that playing through a concussion is not the same as playing through an elbow injury or a knee injury,” Kaufer said. “Having the effects of a concussion and still playing is likely going to make them less effective in performing that sport and also makes them more liable to further injury.”

With technology still in the works and data collection still underway, trainers and other team officials still rely on players to admit when they fear concussion. But often, that doesn’t happen.

“I kept getting concussions during games, and I just wouldn’t come off,” said Caitlin Ball, a former women’s soccer player and current senior at UNC. “I lied to my trainers, and I was like, ‘I’m fine,’ and I kept playing and that made it worse probably.

“I passed all the tests, but you can still pass the tests and not feel like yourself.”

But changes in her state of consciousness — everything from blurry vision to headaches to depression — eventually caught up to Ball.

Eventually, the impact was too great.

‘Why is this happening?’

She prayed.

On that day, Ball’s cathedral wasn’t any building — it was the Carolina Blue sky above her, taunting and reassuring her all at once. Sobbing on the steps of Kenan Memorial Stadium, she looked up and remembered.

She remembered that color, the one she’d worn for almost three seasons as a member of the UNC women’s soccer team.

She also remembered her doctor’s voice, the same voice that just minutes earlier had confirmed she would never wear her uniform again.

Ball, a junior at the time, had sustained another concussion, less than a month after recovering from her last one.

This one made it her fifth in the span of about a year. This one, after she consulted with doctors and family members, would also be the last straw.

But Ball’s case isn’t a rarity. She isn’t the first and she won’t be the last to retire from soccer because of concussions.

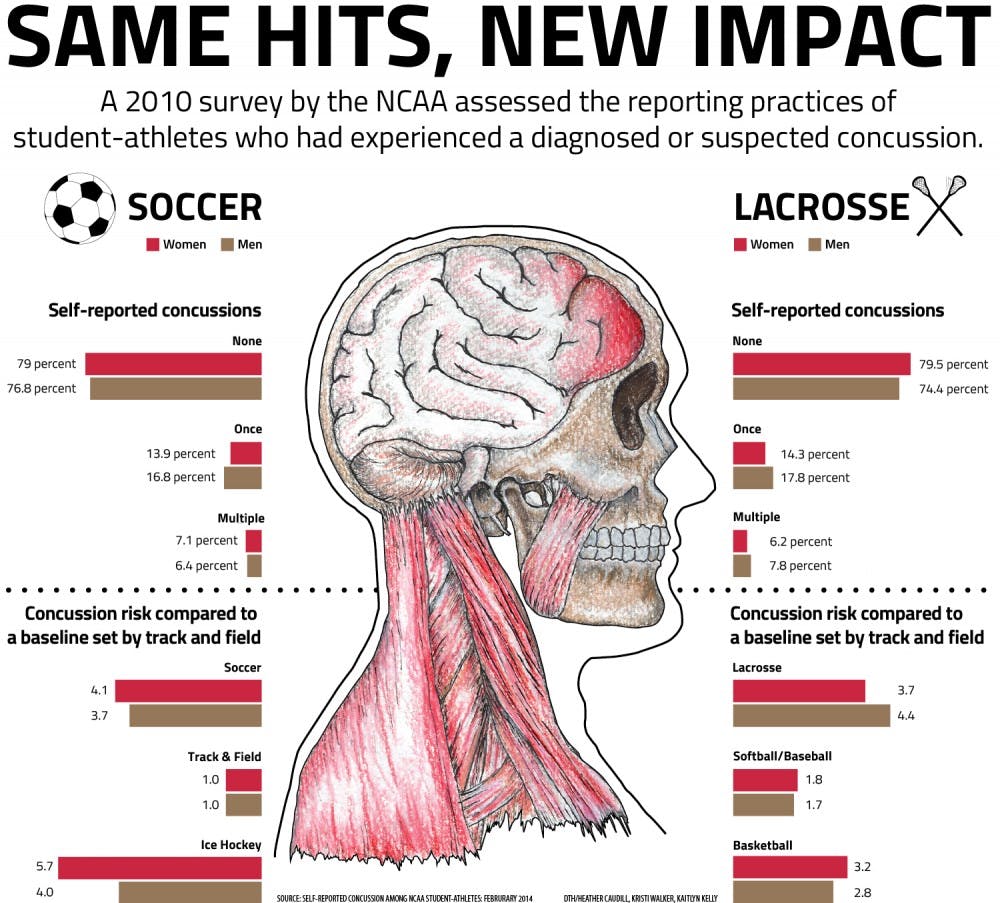

After ankle sprains, head injuries are the most common injury among female soccer players, according to data compiled by the NCAA between 2004 and 2009.

“Honestly, at this point, I was just asking God, ‘Why is this happening? What’s going on?’” Ball said. “It was hard to give up that dream.”

And the goal of medical experts and researchers, as they continue to study head injuries, is that no one else has to do the same.

“I think we just need to be paying more attention to it and making sure that we keep our heads on straight,” Kaufer said.

sports@dailytarheel.com