How we got here

Student fees have been a tradition for almost as long as college athletics. At UNC, athletic fees help pay for students’ free access to all sporting events, as well as maintaining athletic facilities.

That’s not all the fee does, however. While the business of college sports has grown more and more lucrative, particularly in the past decade, expenses have risen at virtually the same rate as profits.

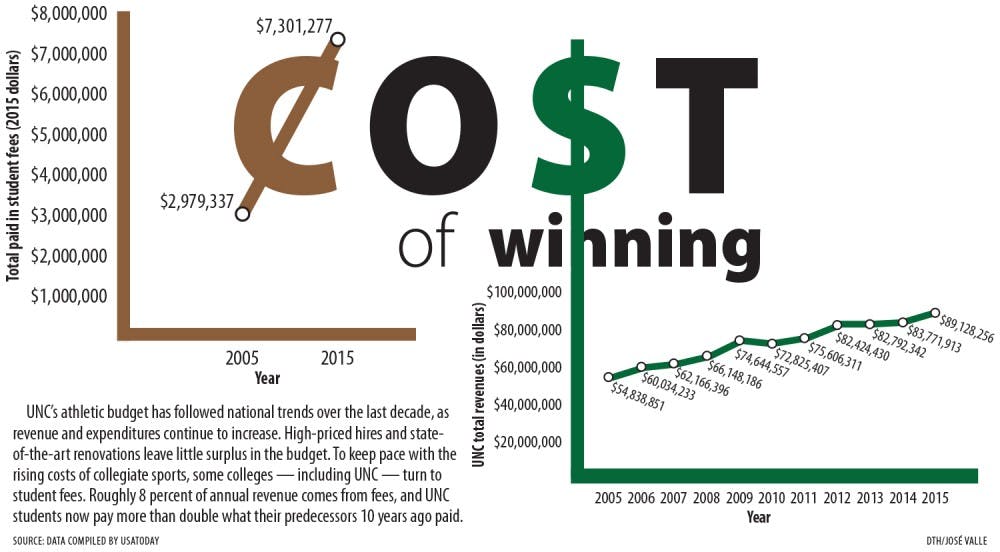

According to a Washington Post analysis of financial reports from 2004 and 2014 submitted to the NCAA by 48 schools in the Power Five conferences, combined revenue for the schools rose from $2.7 billion to $4.5 billion. The 10-year increase in expenses was virtually the same, and that trend is mirrored at UNC.

“If we’ve had any surplus bottom line, it’s not been that significant,” said Martina Ballen, chief financial officer for UNC athletics.

Student fees made up around 8 percent of UNC’s athletic revenue in 2015. With the University’s razor-thin profit margin, UNC would be solidly in the red without student fees.

“We have always tried to look at student fees as a last resort,” Ballen said. “We really try to look at what other sources or ways we can impact revenue to grow revenue. And also to look on the other side, where we can contain or cut expenses.”

The bulk of the increase in UNC’s student athletic fees comes from a $150 hike between 2005 and 2007. The University raised the fee 150 percent in exchange for the athletic department returning the 25 percent of trademark and licensing revenue it had previously received. The concession was well worth it for the athletic department, whose share of that trademark and licensing would have totaled less than $1 million in 2013 — the same year it made nearly $2.5 million in student fees.

The justification for the fee was to increase salaries for UNC’s Olympic sports coaches, who at the time ranked in the bottom third of the ACC in salary, and to pay for renovations to Carmichael Arena.

Many schools around the country follow a similar model. But several schools don’t charge student fees. Out of the nearly $150 million in revenue the University of Alabama made in 2015, none of that came from student fees. Students at Kansas State University currently pay a little over $500,000 in fees — roughly $20 per student — but Athletic Director John Currie plans to phase out student fees by 2020.

Neither school offers free admission to both football and basketball games like UNC, but students can buy tickets or season passes at a discounted rate. That lets students who aren’t as interested in athletics or attending games off the hook for paying for them. While Mayo has certainly gotten his money’s worth out of his fee, other students who never attended a game helped foot his bill. He’d be in the front row of the student section each Saturday even if he had to pay.

“It might have deterred me coming in (to UNC),” Mayo said. “Now that I’m involved and have really gotten passionate about it, there’s no cost that would deter me from going to games.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

An arms race

Jay Smith has looked a lot at college sports in the past several years. He co-authored a book called “Cheated” with Mary Willingham, one of the whistleblowers of UNC’s fake classes, that examines what happens when education isn’t first priority for universities.

“Our athletic departments in this country run professional commercial enterprises,” Smith said. “That means that they’re driven by imperatives that are specific to professional enterprises. They’ve got to win.”

In pursuit of that goal, athletic departments justify spending gobs of money. Coaching salaries at UNC grew from $17 million in 2005 to $31 million in 2015. That includes hiring two new, high-priced head coaches in Butch Davis and Larry Fedora with the purpose of rebuilding the football program — along with firing Davis and extending Fedora’s contract.

Facilities’ costs have also more than doubled in the past decade as the school seeks to attract recruits. It’s a self-perpetuating cycle, as each school is constantly looking to reset the bar in the college sports arms race, making UNC’s new wall of Nike Air Jordan shoes in the men’s basketball locker room seem like a justifiable expense.

“They’re playing in a professional market where that’s what they’ve got to pay coaches, and that’s what they’ve got to do to recruit, and that’s the type of facility that they have to have in place,” Smith said.

For UNC, that investment has paid off in some ways. Just in the past 12 months, the football team had a shot at its first ACC championship since 1980, the basketball team played in the national title game and numerous Olympic sport teams competed in or won national titles.

In 2016, the NCAA and the University also continued to deal with the fallout from a long-running scheme of fake classes to keep athletes eligible and on the field.

That’s the cost of playing the game.

@loganulrich

enterprise@dailytarheel.com

The Daily Tar Heel has been a voice for the UNC and Chapel Hill community for more than 120 years — and continues to train the next generation to enter careers in independent, thoughtful, public-service journalism. To make sure of it, we receive no money from the University.

We firmly believes our newspaper should be free for every member of our community. To ensure the DTH remains an independent voice for our readers, we ask for your support. Become a friend of The Daily Tar Heel, and help make sure we can continue our quality and independence.