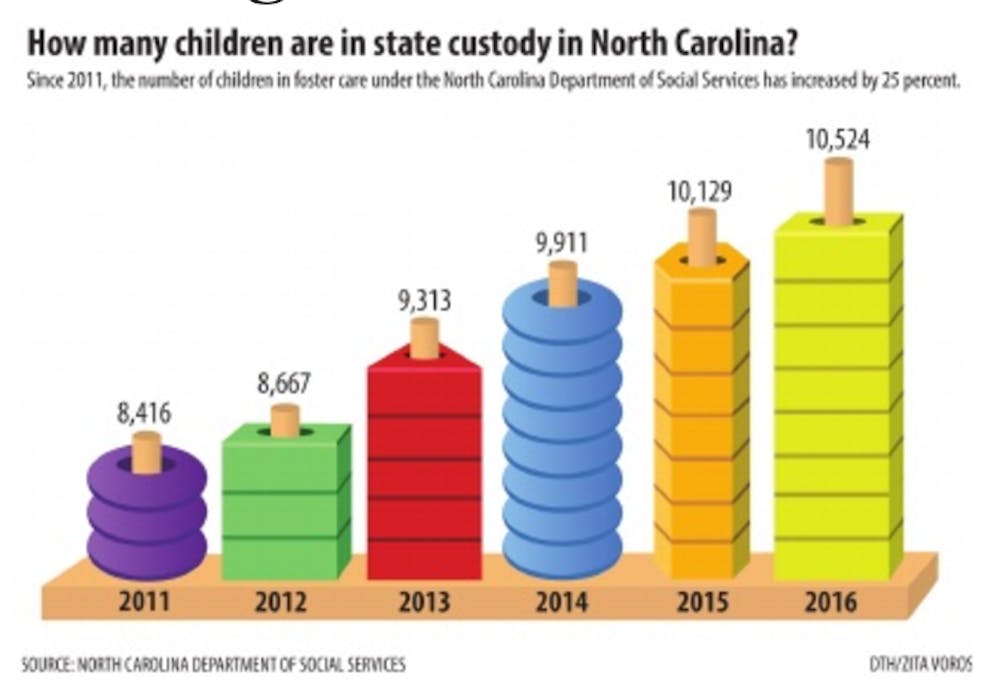

The number of children in the system has increased by 25 percent since 2011. This is cause for great concern if trends continue, said Brook Wingate, the vice president of philanthropy for Children’s Home Society of North Carolina, a nonprofit which provides adoption and foster care services.

Children’s Home Society received almost 3,000 referrals of children needing a home last year, but Wingate said they only have families for 364 children.

“That is not acceptable because Children’s Home Society of North Carolina is the largest private provider of foster care to permanency work, and we are only serving 10 percent of the children referred to us,” she said.

Wingate said the shortage of available families puts additional pressure on the organization to place children.

Dean Duncan, a professor in the UNC School of Social Work, has been collecting data about the state’s foster care system for about 20 years. He said North Carolina’s foster care caseload tends to fluctuate, and today’s levels parallel those of 2000 and 2006.

Wingate said potential causes for the increase in children in foster care custody, including the opioid crisis, changes to the state’s approach towards mental health and poverty.

Kevin Kelley, the child welfare section chief within the state’s Division of Social Services, said the group noticed in late 2012 and 2013 that the number of children coming into foster care was beginning to exceed the number of children able to exit the system.

“The funds available to county departmental services to provide those in-home services to prevent children from coming into care diminished, partly because of the lesser amounts of federal funds that are available,” he said.