“Our philosophy is our job is to protect and serve, and within that statement is protection of life,” he said.

He said making arrests is not a solution to the opioid misuse problem.

Other police departments in the state, like Wilmington and Fayetteville, follow the same philosophy and participate in Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), a program that aims to divert people addicted to opioids from prosecution in the criminal justice system and get them help.

LEAD allows officers to identify individuals frequently involved in the criminal justice system with an underlying substance use issues or substance use disorders and refer them to treatment services.

Melissia Larson, LEAD coordinator for the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition, said jail was never intended to be the biggest mental health institution a community has.

“So we really have to be more innovative and resourceful with the assets that we have in a community and try to redirect to what people really need,” Larson said.

She said Wilmington, Fayetteville, Hickory, Jacksonville, Waynesville and Statesville are – or plan to be – LEAD participants.

Getting the help they need

In a prominent intersection in Wilmington, a man overdosed on opioids and passed out while driving. He killed a 2-year-old boy and injured the boy’s expectant mother in the 2016 accident.

According to Tony McEwen, assistant to the Wilmington city manager for legislative affairs, the man had been brought back from an opioid overdose five times using Narcan, a nasal spray form of Naloxone.

In response to the question about what to do with people who have been brought back from an opioid overdose, the mayor’s task force in Wilmington created a quick response team.

If an individual refuses treatment at the scene of the overdose and is released, the quick response team – a law enforcement officer, substance abuse counselor and someone from the medical field – follows up with them within 48 hours.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“They build relationships with those people,” McEwen said. “They offer them treatment services, educate them on what may be free out there, what insurance covers, that type of thing.”

If the individual denies treatment again, the quick response team follows up with them in another 48 hours.

“It’s just this ongoing cycle of communications and relationship building, which doesn’t sound like rocket science, but it’s worked elsewhere, and so that’s what we’re going to be replicating here in our community,” McEwen said.

Project Lazarus — a nonprofit started in Wilkes County to support prescription medication issues — is helping equip communities with the help residents need to overcome addiction.

The project promotes an increase in addiction treatment in communities and uses peer guides, who are people in long-term recovery that help others find their way through treatment and recovery.

According to Fred Wells Brason II, founder, president and CEO of Project Lazarus, it has helped almost every county and community in North Carolina with the opioid misuse problem.

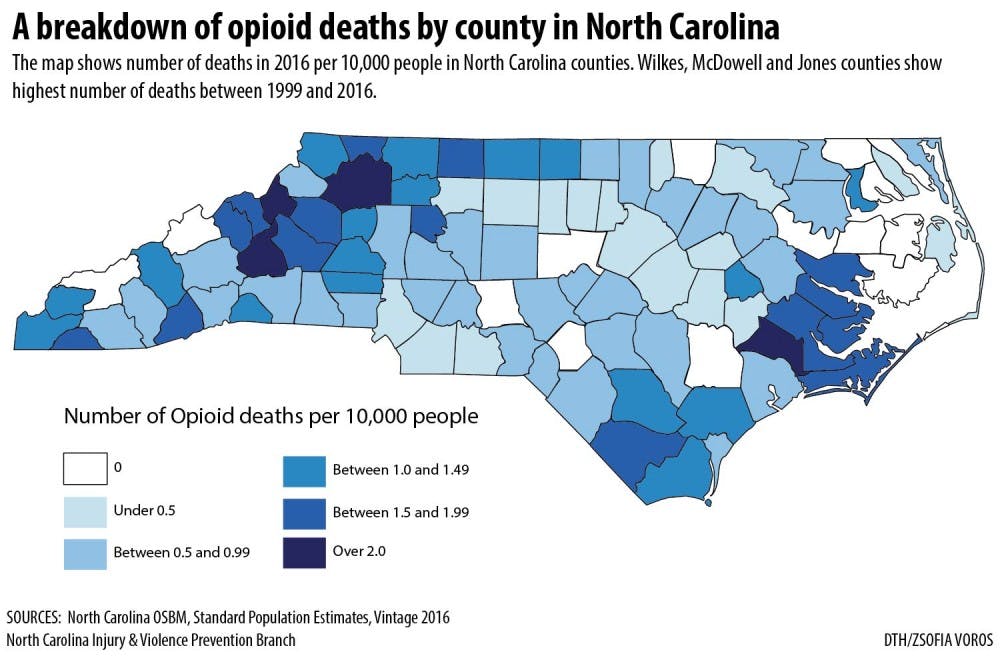

Programs like Project Lazarus are especially important for rural communities in North Carolina, like Wilkes County.

Wilkes County has had the highest rate of opioid-related deaths per capita and per 10,000 between 1999 to 2016. The county has a population of 70,027 and in 2016 saw 25 opioid-related deaths.

Ann Absher, director of the Wilkes County Health Department, said opioid misuse affects rural counties more than others because of high rates of poverty, unemployment and an inability to find treatment resources.

“We don’t have as many providers that do the medication or the substance abuse treatment,” Absher said. “We don’t have access to substance abuse treatment like you would have in a larger facility, especially treatment for those that are uninsured.”

Prevention and education

Part of solving the opioid misuse problem is preventing addiction to the drugs, educating communities on the issue and changing the way opioids are prescribed.

A group working toward these reforms is South East Area Health Education Center in Wilmington. The center, which has locations across the state, has a mission to provide quality education, training and resources to health providers in southeastern North Carolina.

SEAHEC provides training for prescribers on CDC guidelines for prescribing opioids. It also provides training on treating pain through complementary therapies, which don’t include opioids and often don’t include medication.

It has also provided trainings for the community on the problem and what is being done about it.

Olivia Herndon, director of continuing education, mental health and public health at SEAHEC and New Hanover Regional Medical Center, said physicians were trained differently when opioids were first prescribed.

“They were told they were not habit forming, that they were not dangerous for the majority of patients,” she said. “We now know that obviously was false information.”

Project Lazarus is also involved with advocacy on how to prevent opioid addiction by educating prescribers and communities. To do this, they work with health departments, local governments and other groups.

Another preventative measure is the Strengthen Opioid Misuse Prevention Act, which was signed by Gov. Roy Cooper in June of 2017. The act mandates the use of a controlled substance registry called the Controlled Substance Reporting System.

This registry allows prescribers to check if patients have been prescribed opioids in the past to decrease the number of pills a patient can get from a clinic.

Herndon said when it comes to education and prevention, health systems can’t work alone.

“Our health system can’t do this without our court system, and our court system can’t do it without our school system and our transportation system and our housing system and our churches,” she said.

@baileysaldridge

special.projects@dailytarheel.com