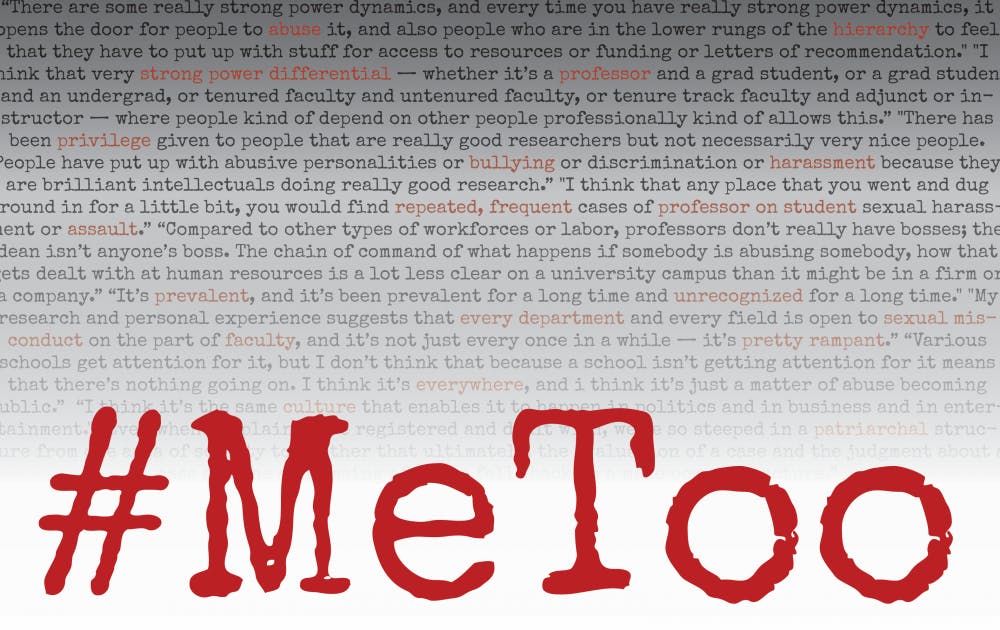

Marin-Spiotta said the strong power differential in relationships — like those between a professor and a graduate student or a graduate student and undergraduate student, for example — where people sometimes depend on others professionally allows this.

“People have put up with abusive personalities or bullying or discrimination or harassment because they are brilliant intellectuals doing really good research,” she said.

UNC’s Policy on Prohibited Discrimination, Harassment and Related Misconduct, created in response to Title IX, applies to both on and off campus conduct of University students, University employees, postdoctoral scholars and others connected to the University. It prohibits “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal, physical or electronic conduct of a sexual nature that creates a hostile, intimidating or abusive environment.”

Students are encouraged to report prohibited conduct to the Equal Opportunity and Compliance Office — or to law enforcement for the purpose of pursuing a criminal investigation — within 180 days of the alleged act. Anonymous reports are allowed, but “the University’s ability to respond to an anonymous report may be limited depending on the level of information available about the incident.”

After an internal investigation, administrative reviewers prepare a written report containing “factual findings, a summary of witness statements, a determination of whether the policy has been violated and the resolution of the complaint, including any corrective actions recommended or taken.” These are all subject to confidentiality protections provided by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

Leto Copeley, an attorney at Copeley Johnson and Groninger PLLC who does work with victims of sexual harassment and assault, said while she has taken up several cases against various public and private universities based on failure to protect a student’s rights during the Title IX process, UNC is making great efforts to address students’ concerns and keep students safe.

She said the University has made big changes in response to student complaints made five years ago to the U.S. Department of Education claiming UNC violated the rights of sexual assault victims and facilitated a hostile environment for students reporting sexual assault.

“I really feel like the Title IX complaint process is much more fair than it used to be, and I encourage students if you have been sexually assaulted on campus to make that report sooner rather than later,” Copeley said.

Lewis said although various schools get attention for cases of sexual harassment, it may still be happening in places that are not getting that kind of attention.

“It’s just a matter of abuse becoming public, either through the diligence of student reporters, or through a survivor coming forward, or a group of survivors coming forward and registering complaints, or on rare occasions, other faculty members who are observing the behavior of one of their colleagues and reporting it to the administration,” she said.

Higher education has the same culture that enables sexual harassment and assault to happen in politics, business and entertainment, Lewis said.

“I think that any place that you went and dug around in for a little bit, you would find repeated, frequent cases of professor on student sexual harassment or assault,” she said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Lewis said the patriarchal power structure has allowed men to believe for centuries that they can abuse their power and get away with it.

“Even when complaints are registered and dealt with, we’re so steeped in a patriarchal structure from one area of society to another that ultimately, the evaluation of a case and the judgment about a case and the addressing of a case falls back on a male power structure,” she said.

Changes can also be made with the U.S. Department of Education, Copeley said. She said the Department has made the reporting process more confrontational by requiring victims to face both their accused and their attorney if they choose to hire one. The Department’s proposed guidance also suggests students be offered mediation, which the Barack Obama administration eliminated.

Marin-Spiotta is working on a program funded by the National Science Foundation to develop strategies to try to change this culture and to train people to think about ways they can intervene.

“We’re developing bystander intervention training to address harassment and then also developing resources to train department chairs to deal with harassment or bullying or discrimination and how you build a more inclusive climate,” she said.

Lewis said one solution is making people aware of the pain these abuses cause people. She has interviewed survivors with experiences dating back decades that have made career changes because of the abuse they suffered in graduate school or as undergraduates.

“Bringing people’s attention to how damaging this is is one component,” she said. “I think more women in more positions of power and more men and women saying, ‘This is unacceptable.’”

@beccaheilman

state@dailytarheel.com