The focus on these new prescribing practices helps doctors prepare to handle patient pain. At Duke, physicians faced similar challenges: they did not have the proper training to know how to prescribe opioids safely, said Cynthia Kuhn, a Duke professor of pharmacology.

“There were a lot of challenges to well-meaning physicians because they didn’t really quite have the right education to know how to (prescribe opioids) safely,” Kuhn said. “They were being told that they needed to adequately treat pain, they started using (opioids) for situations where they might not have been appropriate. Patients started figuring this out super fast.”

At UNC, Chidgey expanded the focus on opioids outside of the typical modules that are designed to teach about painkillers. For example, opioids can have significant gastrointestinal effects including constipation, which allows the medical school to teach about opioids while they cover gastrointestinal issues.

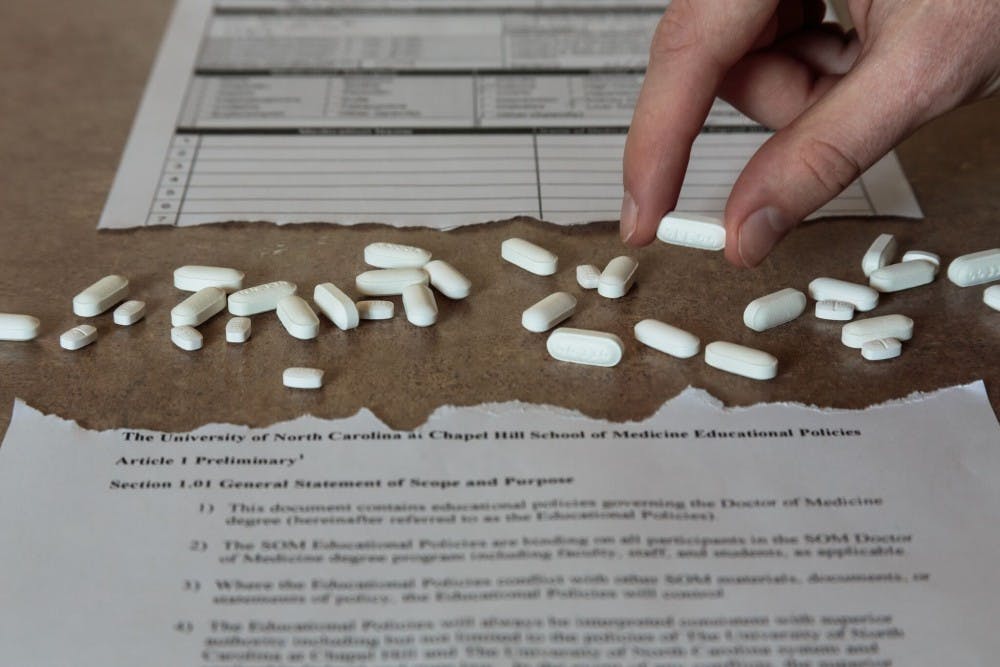

Although teaching UNC students how to prescribe drugs is important, the new curriculum is designed to teach students to do more than prescribe opioids safely.

Chidgey has put an emphasis on teaching that there are other options for dealing with patient pain than prescribing an opioid.

However, other painkillers don’t approach the level of effectiveness that opioids can reach, said Tao Che and Daniel Wacker, postdoctoral researchers in UNC’s School of Medicine.

Opioids block pain signals when they reach the brain and are especially effective at targeting acute pain such as pain experienced after a surgery. Other painkillers can only block pain at a localized point in the body, instead of eliminating all pain, or are only effective against more dull pains.

“Here, generally, we start with an opioid and then we add on other things if those aren’t working,” Chidgey said. “And really, the better thing would be to start with these other options and then eventually go to the opioid only if necessary.”

Despite these changes, UNC medical students will encounter a patient culture that has different expectations than what they have been taught to meet.

Former medical practices have also created a harmful culture of pain prevention in patients. Patients now expect that doctors will eliminate their pain completely, Chidgey said. Doctors have continually asked patients how much pain they're experiencing, which warped patient expectations over time.

The answer, Chidgey said, is enabling students to educate their patients about the dangers and proper uses of painkillers in the future.

“You get to the point where the assumption is almost that you should not have pain, and that if you do, something should be done about it when the reality is, you know, life is painful,” Chidgey said. “Just because there is some pain doesn’t mean there needs to be an opioid.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Targeting new research

Terry Kenakin, a professor in the department of pharmacology, said recent breakthroughs in pharmacology have revealed it’s possible to shape a drug molecule to specifically target individual receptors.

“Hypothetically, we can design an opioid that makes whoever takes it feel incredibly nauseous instead of the euphoric effect that the current opioids have,” Kenakin said.

The implications of this new breakthrough were exemplified by the findings of Bryan Roth, a researcher and professor in UNC's Department of Pharmacology, along with a team of other scientists.

The team recently released a study which showed it was possible to target only the Kappa opioid receptor with a drug, which would eliminate the euphoric feeling that accompanies opioid consumption and replace it with dysphoria.

The department of pharmacology is using this new breakthrough to promote opioid research to their students.

Duke’s reforms

Despite these changes in the UNC curriculum, Duke has been working on opioids and related curriculum for over ten years, putting them far ahead in the process of educating their students about opioids.

Kuhn said she started teaching about the biology of addiction in her classes at Duke ten years ago. This preliminary step allowed Duke to quickly develop additional addiction and opioid curriculum five years ago when the problems with opioid addiction became apparent.

Duke’s changes have been significant and reach throughout all levels of their medical school.

Kuhn has also changed her lessons to provide more tangible advice on how to prescribe opioids.

Kuhn said that Duke may have had an advantage in developing their opioid curriculum and expertise, since all three of the members who develop curriculum for their pharmacology department are neuropharmacologists who study the way that drugs affect the brain.

“I’ve always told (my students), ‘Every single opioid is potentially addictive,’” Kuhn said. “But what we’ve done in a far more concrete way is say, ‘OK, you have control over access that patients have and you have to exert control.’”

The pharmaceutical industry

Kuhn said that another key player in how opioids get prescribed is the pharmaceutical industry.

“It has been revealed that, of course, (they've) been highly complicit in that they have been narrowly marketing amounts of opioids that are in the vast excess to what is required clinically,” Kuhn said.

But Kenakin, a former drug industry employee, pointed out that the drug industry was merely providing a tool for doctors to use to help their patients. He said that the lack of education, both on the part of the doctors and the patients, led to the inevitable misuse of such a powerful tool.

Frank Allison, the program coordinator for collegiate recovery initiatives at UNC, said UNC lacked an on-campus space where recovering addicts could come to as a place to support their lifestyle of abstinence.

“Most campuses have a drop-in space, a space set aside for students who are in recovery to get away from an abstinence hostile environment,” Allison said. “The campus is a hostile environment for recovering students who are striving for abstinence, and they could use a space to get away and be among fellow former addicts who are also practicing abstinence.”

Despite the resources UNC is missing, Kuhn praised the work that Roth is doing in the pharmacology department by using modern medical techniques to develop new drugs.

She also praised the work that UNC's Horizons Program is doing, a substance use disorder treatment program for pregnant and/or parenting women and their children.

Chidgey said UNC is working hard to educate medical students, as well as residents and fellows, and is hopeful that education will turn the tide of the epidemic.

“I think the more that we can spread the word, the better,” she said.

@NewkirkSeth