After Brown v. the Board of Education, North Carolina legislature approved The Pearsall Plan, which was designed to slow down desegregation. This plan required parents to request a transfer if they wanted their child to attend a school of a different race.

Although Brown v. Board of Education recently passed, in 1959, Stanley Vickers requested a transfer to an all-white school but was denied. The Vickers family sued, and in August 1961, they won the lawsuit. Thurgood Marshall, the first black United States Supreme Court justice, was one of the lawyers in Vicker’s case.

All transfers were allowed in 1963 to 1964 and school district lines were redrawn to assign equal percentages of black and white students to the schools.

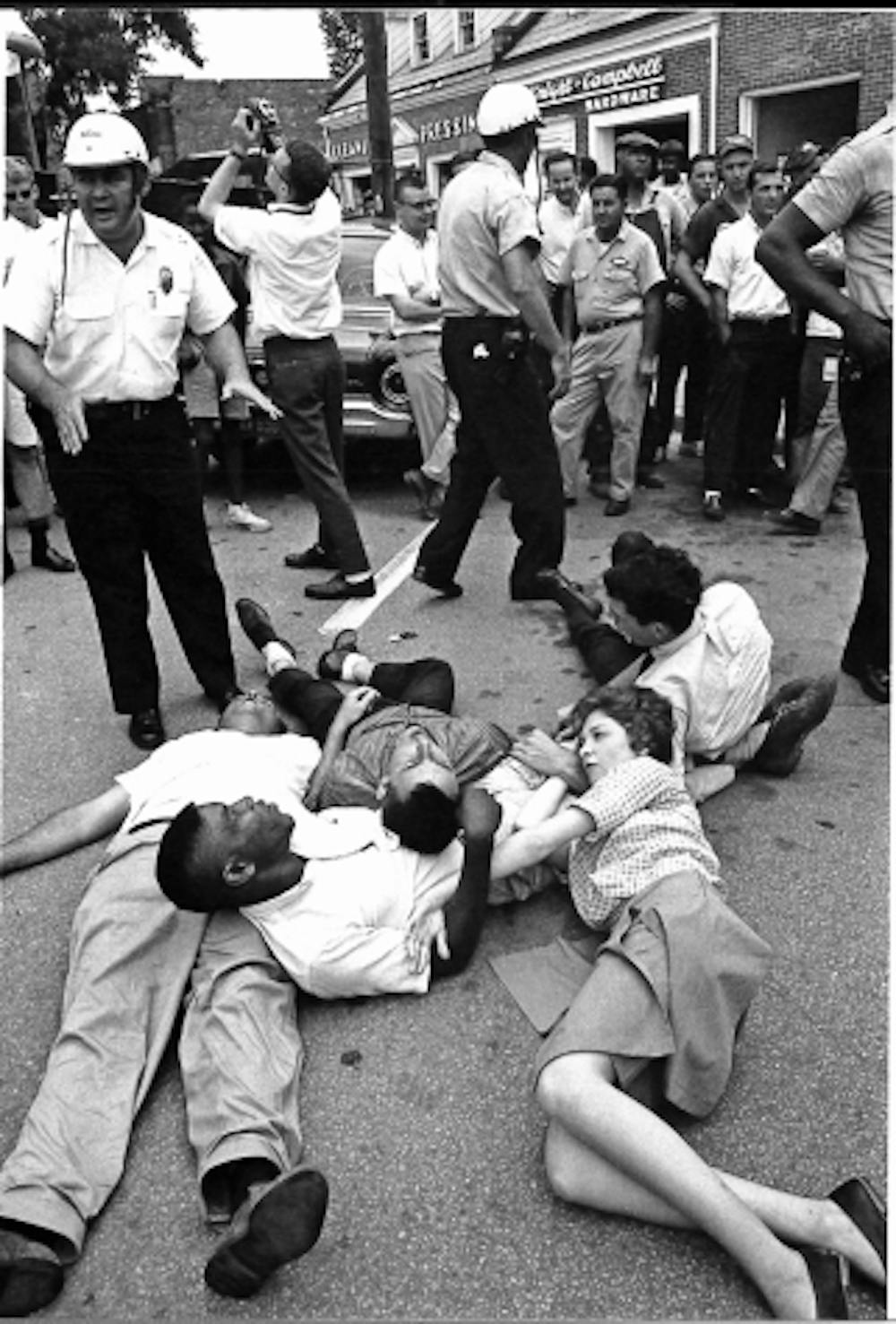

The early 1960s

Susan Worley, a white woman who was a Chapel Hill student in this era, said even children were aware of what segregation meant.

“One thing that is hard to convey to people now is what a big deal the whole Civil Rights movement was for everybody, for black citizens and for white citizens,” she said. “I could’ve told you where every kid in my class stood on the issue because it really dominated everything and of course it should have — it was a very weird Jim Crow world.”

Stone said when she integrated to Guy B. Phillips from Northside Elementary in 7th grade, it was like moving to a different country. Her brother, Ted M. Stone, originally attended Lincoln High in 1961 and was one of the first black students to integrate to Chapel Hill High School.

“I always sat in the back, in the corner, away from everybody,” she said.

Stone said when she went to Chapel Hill High School, there were fights almost every day between races.

“They didn’t want us, and to be frankly honest with you, we didn’t want to be there,” she said. “We were trying to keep our mouth shut and have kind of the theory of Martin Luther King.”

One time, Stone was at gym class and she didn’t have a comb to brush her hair. She asked a white classmate, whom she thought was her friend, if she could borrow her comb, and the white student told her to ask another Black student. Stone said she would never forget that moment, or the white student’s name, because she felt that she was thought of as something dirty and inferior.

She remembers the fear she felt everyday from racial slurs and threats.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“My mom would tell me when we approached anyone white, move to the side and let them pass and don’t make eye contact,” she said.

The late 1960s

Even after integration, many black students felt that they didn’t belong. When Worley attended Chapel Hill High School in 1968, black students who came from Lincoln High and the other black schools protested to make their voices heard.

“When the schools were fully integrated, everything stayed as it was for the white schools and all the traditions from the Black schools were lost,” she said.

Worley said the black students had to sacrifice everything, including the name of their school, their mascot, their principal and their coach.

Burroughs said Lincoln High had stories worthy of history, and they won many championships from competitions with other black schools.

“When (Chapel Hill High School and Lincoln High) merged, someone threw away the Lincoln High trophies,” she said.

Worley said after the Chapel Hill High School protests in 1968 and 1969, the student body at Chapel Hill High School voted to change the name of their mascot to the Tigers, which was the former mascot at Lincoln High School.

N.C. Sen. Valerie Foushee, D-Chatham, Orange had to integrate to Guy B. Phillips Middle School in 1969. She said in high school, there were many sit-ins and peaceful protests.

“Let’s be clear — every day somebody used the n-word,” she said. “We were fighting to be heard, to be considered, to be recognized and to be treated equally.”

She said some white people considered black students to be inferior.

“There were no expectations that we would do well in any classes,” she said. “There were situations where we wouldn’t be invited to take classes of rigor because there were no expectations that we would do well.”

Foushee said when she was accepted into UNC, white students said the only reason she and other Black students were accepted was because of the quota system.

Stone said her negative experiences prepared her for her life.

“Sometimes the hardest things you do make you stronger even when we go through them,” Stone said. “Even though there were a lot of negatives, to go through those negatives made me a better person.”

city@dailytarheel.com