Hurricane Florence drowned 5,500 of the North Carolina’s 9 million hogs, but the hurricane’s worst impacts were on the lagoons that hold the hogs' waste.

Since Hurricane Florence, at least 32 lagoons have discharged hog waste into the surrounding area. Nine lagoons have been inundated by floodwaters, and at least 17 lagoons have no space between the level of feces and the ground, likely leading to the waste spilling over the sides of the lagoon. Five lagoons have been structurally damaged.

Duplin County Fire Marshal Ricky Deaver said there is no telling how long it will take to clear all of the damage.

These lagoons were already a point of contention between farmers and environmental and health advocates.

The county's hogs produce 15,700 tons of waste a day, about twice the amount New York City’s entire population produces daily. The lagoons store the untreated waste, and farmers often spray the feces across agricultural fields to dispose it and use as fertilizer. In some cases, this contaminates groundwater and passes into the properties of neighboring homes.

On Sept. 19, The North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services released a tweet containing a quote from Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler while flying over Eastern North Carolina.

“What I saw from the air was almost indescribable,” he wrote. “I saw water that looked to be higher in areas (than) during Matthew. I would simply say it looks like utter devastation.”

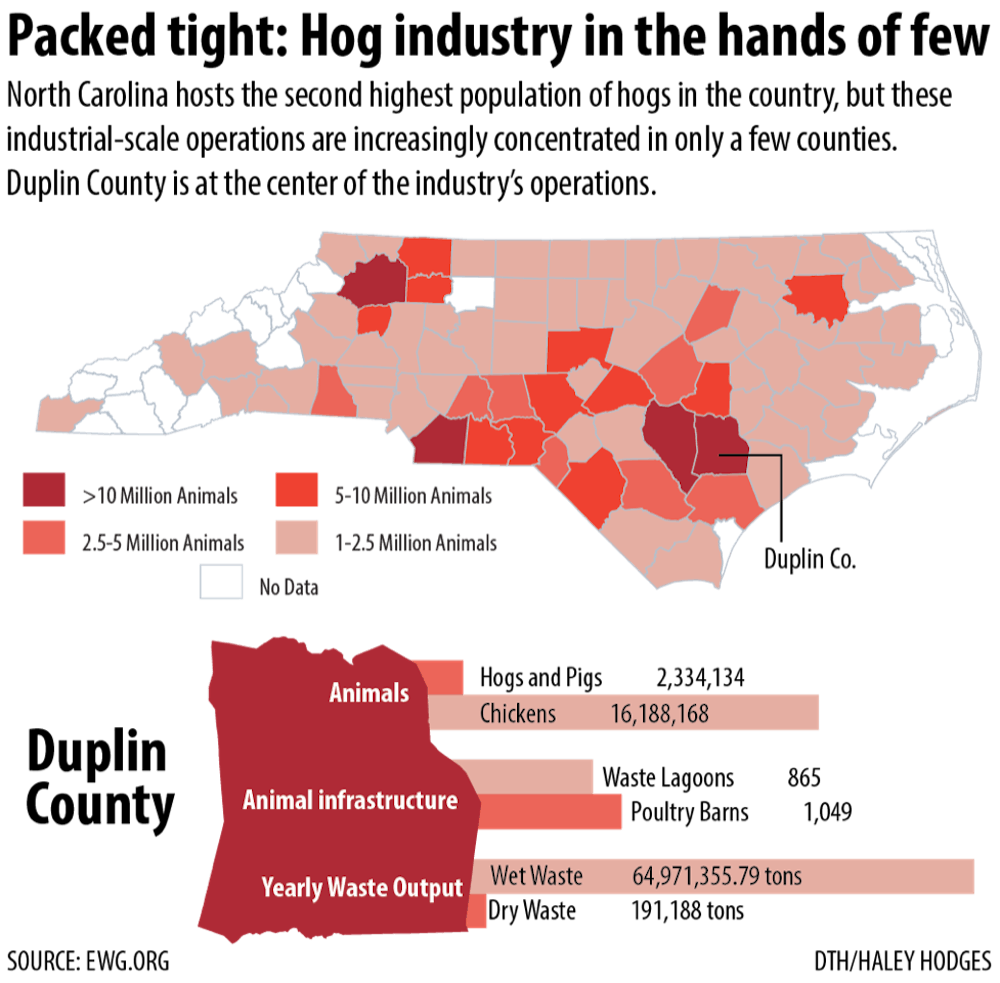

As farms become more concentrated, so do their environmental impacts.

From 1982 to 1997, the number of hogs grew by over 1 million in North Carolina, the state responsible for more than 95 percent of the national increase in hogs. During this time, the number of North Carolina hog farms shrank from 8,691 to 2,673.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the world’s livestock contribute to 14.5 percent of annual greenhouse gas emissions. Hog feces release methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times as potent as carbon dioxide.

Sophomore Mariana Price grew up in Wallace, working on her uncle’s two chicken farms on both sides of her house. In one of the three lawsuits settled, one of Price’s father’s friends lost his farm.

“I do see the environmental stress – I know all that,” Price said. “But most of the farmers are following regulations, so I don’t think they’re purposefully being neglectful. A lot of them I think are just a little bit ignorant.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

The nutrients from the hog waste also enter water systems and the air, leading to bouts of strong odor and water pollution, among other effects. And residents in Eastern North Carolina often rely on well water, Longest said.

Exposure to these particles increases the risk for some respiratory diseases in adults and asthma in children.

Farmers often fail to understand these environmental and health impacts, Price said.

“They’re not open to listening or hearing the other side of the story,” she said.

Small towns lash back

Ryke Longest, the director of the Environmental Law and Policy Clinic at Duke University School of Law, sees the hog farms as a threat to human health, food systems and ecosystems on which people depend.

But local residents are hard-pressed to bring these issues to court. Instead, they've sued pork companies for their decreased property values.

During the summer, the third and largest lawsuit of its kind was settled, where plaintiffs argued hog farms impeded their right to use and enjoy their property. The federal jury awarded more than $470 million to six neighbors of a hog farm in Pender County, located south of Duplin. Due to a state cap on the amount of money plaintiffs can receive, the total award was lowered to $94 million for the six neighbors.

Despite the seemingly victorious lawsuit, other residents in pork-producing towns are fighting back.

The general attitude among community members is that plaintiffs are money-grabbing and attacking family farms, Livingston said.

“It’s kind of perverse that they see it as the family farmer, when really they’re contract laborers,” Livingston said. “The kind of small family farm you see in movies doesn’t really exist anymore.”

Price, too, sees the backlash faced by opponents to industrial farms. Price’s friend’s parents were involved in a recent lawsuit against Smithfield Foods, a large pork-producing company. Her friend declined to comment for this article, citing fear of the response from his town.

Naeema Muhammad, the co-director of organizing for the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network, considers the recent lawsuits a victory against large corporations.

“Industry was making them feel like they were making this stuff up," Muhammad said. "They were making them feel like they needed to choose between their way of life and jobs."

Many of these residents own homes that have been passed down for generations, Muhammad said, and these homeowners are disproportionately African American, Latinx and Native American. For this reason, the hog industry has become one of the largest opponents of environmental justice groups, which advocate for marginalized communities impacted by environmental issues.

“People do not have the means to pick up and move just because something is happening to them,” Muhammad said.

Not only do residents lack the financial means to move, but they are also increasingly limited in their options for legal remedies.

In recent decades, farm advocates have attempted to pare back laws protecting neighbors of farms, Longest said. Senate Bill 711 is the latest in a series of statues that rewrite the law surrounding property rights.

The legislation effectively protects all hog farms from nuisance lawsuits going forward, Longest said.

“What we’ve done with (Senate Bill) 711 is said, ‘You have the right to use and enjoy your property unless there’s a farm next to you, in which case the farm has a right to do what it wants to do,’” Longest said. “Pretty soon there will be nothing left in terms of neighbors’ rights.”

An economic powerhouse

Not only do the farms themselves generate much of the county’s tax income, but so do the businesses that provide for the farms, such as feed companies, gas stations and trucking businesses.

“The joke was that whenever you smelled it, that was the smell of money,” Livingston said.

Price fears the already underfunded school district would suffer even more if regulations were to reduce the industry’s tax contributions.

“Our education system would just really plummet,” Price said. “People say there’s not going to be any money for us.”

While the industry is growing, many independent farmers are losing their jobs, Longest said.

Small farmers are systematically driven out of business because there are only a few buyers, who entirely dictate the terms of production to all of the meat sellers, Longest said.

“The problem I see, like with many environmental problems, is the income and wealth that’s being generated by those businesses is in part being generated because we have allowed impacts to fall unfairly on the shoulders of the neighbors,” said Longest.

Students and environmental advocates agreed corporations should shoulder more of the environmental burden.

Muhammad said she wondered why Smithfield can afford to pay hundreds of millions to its chief executive every year, but “they can’t afford to put clean technology on the ground?"

"Something’s wrong with that picture,” she said.

Large corporations like Smithfield Foods often leave farmers with the costly cleanup, Livingston said.

“They’re people too,” Livingston said. “It’s just a product of the system the corporations have created.”

@emilygalvin34

special.projects@dailytarheel.com