Each fall for the past 13 years, David Adamson has wondered if he’s going to get his job at UNC back.

As a part-time professor in the department of dramatic art, he has to consistently renew his one-year contract, a task that makes it difficult for him to make long-term career plans.

Adamson is part of a growing number of fixed-term faculty employed at UNC and universities across the country, hired to bring in professional expertise and keep academic costs down.

“People in my position are a bargain for the University,” he said.

As the number of fixed-term faculty members has grown, so has the need to clarify these sometimes hazy positions. Administrators have said they are going to place a high value on reforming the way they deal with these roles throughout discussions this year.

Fixed-term faculty members, or non-tenure track faculty, are employees whose appointment is dependent on contractual terms for limited periods of time. These contracts can be and usually are reinstated.

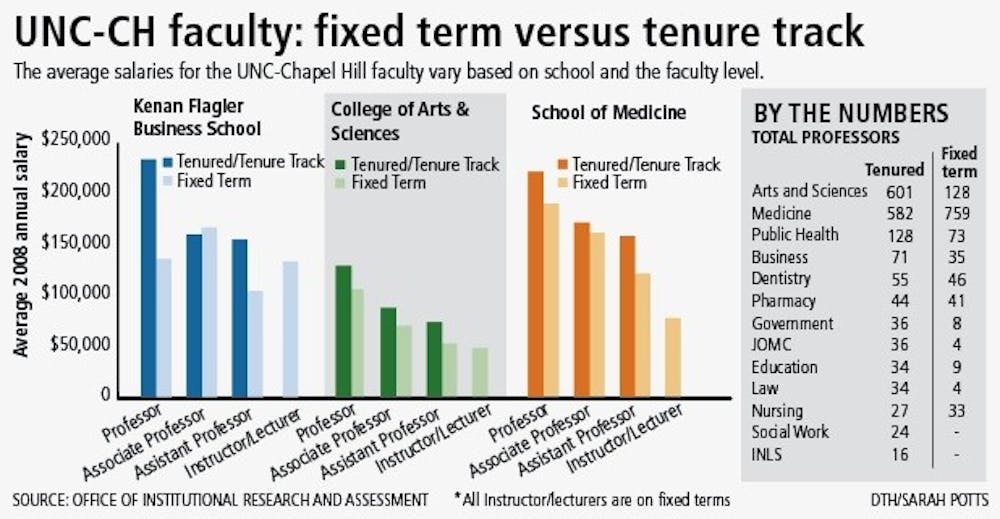

Of the roughly 3,000 faculty members at the University, more than 1,190 are defined as fixed-term.

Most of these fixed-term faculty are part of the School of Medicine in high-paying and highly skilled positions that provide easy opportunities for transition to employment outside the University. But the same guarantees don’t necessarily extend to faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences.

“We would like fixed-term faculty members to treat their positions here as a long-term, rewarding career path,” said Ron Strauss, executive associate provost.

Those rising numbers are common in research universities across the country, according to the 2009 book, “Off-Track Profs: Nontenured Teachers in Higher Education,” by John Cross and Edie Goldenberg.

“Fixed-term faculty are growing as a percentage of total faculty faster than those on the tenure track,” said Goldenberg, a tenured professor in the political science department at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor.

One major reason for bringing non-tenured faculty members is to save money. Often these faculty members do not work enough hours to receive benefits and can have their positions cut when contracts expire.

But the increased presence of these faculty members is due to a variety of factors, Goldenberg said, extending beyond the simple issue of budgets.

“For artistic departments, such as music, drama, creative writing and the like that like to have people with professional experience, fixed-term, part-time faculty members can bring expertise, even if they aren’t interested in being full-time professors,” Goldenberg said.

As recently as 10 years ago, fixed-term faculty were often not treated as an active part of the College of Arts and Sciences, said Bill Andrews, associate dean for the fine arts and humanities. But as their numbers and length of service has risen, the need for further recognition of their contributions has grown.

Progress has been made in recent years, professors said. Fixed-term faculty members can now participate in the Faculty Council if they meet certain employment criteria. They also are eligible for health and retirement benefits if they work an appropriate number of hours.

Administrators said at a recent Faculty Council executive committee meeting that they expect to make permanent a preexisting fixed-term committee within the Faculty Council.

But an overall problem for fixed-term faculty is a lack of definition of their positions within the larger framework of the University, several administrators said.

Often there is inconsistency between departments — sometimes titles used across the board don’t always come with the same responsibilities and roles.

“We assembled an absolutely bewildering list of titles during our research,” Goldenberg said.

In some graduate schools, such as the School of Medicine, roles are clearly defined for each title. But the same level of consistency doesn’t apply to all departments.

Faculty Chairwoman McKay Coble, once a fixed-term faculty member, has made clarifying their roles and reforming the promotion process a major focus.

“There’s been a national trend towards clarity in regards to fixed-term faculty,” Coble said. “The question now is, how can we reward these extraordinary and essential people in every department?”

For Adamson, there’s no question of his role in the department. This fall, he serves as the director of undergraduate studies in the department of dramatic art.

But he would appreciate more clarity and consistency in his position — and a little more job security.

“I would like more work, more hours,” he said. “But as an actor, I’m used to going from job to job.

“That’s the deal we signed at the beginning when we decided to act.”

Contact the University Editor at udesk@unc.edu.

Fixed-term faculty role is hazy

UNC-CH faculty: fixed term verses tenure track