Part of the pressure to ramp up alcohol law enforcement last fall came from community groups like the Coalition for Alcohol and Drug Free Teenagers of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, which has secured two grants worth about $100,000 each to combat underage drinking.

Some of that money went to Chapel Hill’s new alcohol law enforcement task force, ALERT, as part of what District Attorney Jim Woodall called “a new emphasis” on underage drinking.

“I do think that the attention given to the issue is something that is on law enforcement’s radar screen,” said coalition member and retired superior court judge Ryan Bogle.

“They devote their resources to areas where there are concerns within a community.”

Busting big parties often leads officers to “jump to the next step” before finding probable cause that underage drinking is going on, Woodall said.

“Whenever there are four officers, and let’s say there’s 50 people at a party, each officer essentially has a dozen people to account for,” he said. “That’s what makes it real tough. They have to make real quick decisions when they’re dealing with overwhelming numbers.”

Woodall added that people have always challenged alcohol cases, and the recent decisions are not affecting policy in the district attorney’s office.

One case dismissed last week focused on an ALERT police team that entered the Warehouse apartments on Rosemary Street without a warrant in September.

Originally responding to noise complaints, the ALERT squad did not allow students to leave the scene that night, asking them to “prove” their innocence by submitting to a Breathalyzer test, according to a defense motion and police video of the event.

Defense documents state that one officer jammed his foot in an apartment door to prevent a student from closing it and told her, “You are not going back into your apartment unless I go with you.”

“The enforcement method that apparently has been adopted is one that we haven’t seen in other areas of the criminal law,” said Chapel Hill attorney Steve Bernholz, who represented two students charged in the Warehouse incident.

“It’s a Fourth Amendment issue. When you round up students who have been raised to be truthful and cooperate with police, you have essentially corralled them often without any reasonable suspicion.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Suczynski’s case was dismissed on the grounds that police had detained the entire party, about 50 students, without reasonable suspicion and probable cause for everyone in attendance.

On the night of the party, police responding to a noise complaint on McDade Street arrived at the scene and asked everyone in the house to come outside, according to defense documents.

Anyone who tried to flee was pursued, caught and brought back. Police then asked, by show of hands, who was 21 and had been drinking.

“It felt very forced,” said one student who was charged at the party, but accepted a guilty plea bargain instead of fighting the misdemeanor charge in court. She was granted anonymity for this story because she plans to get the charges expunged.

“There’s only one way in and one out, and there were five police cars.”

Though more students are challenging their tickets than in the past, police say they have not fine-tuned their policy in response to this fall’s cases.

Matthew Sullivan, a Chapel Hill police crisis counselor and legal adviser, said he was not aware of any departmental meetings to address alcohol citation policy.

“It’s our obligation to respond to the courts,” Sullivan said, though he declined to discuss policy on a general or case-by-case basis.

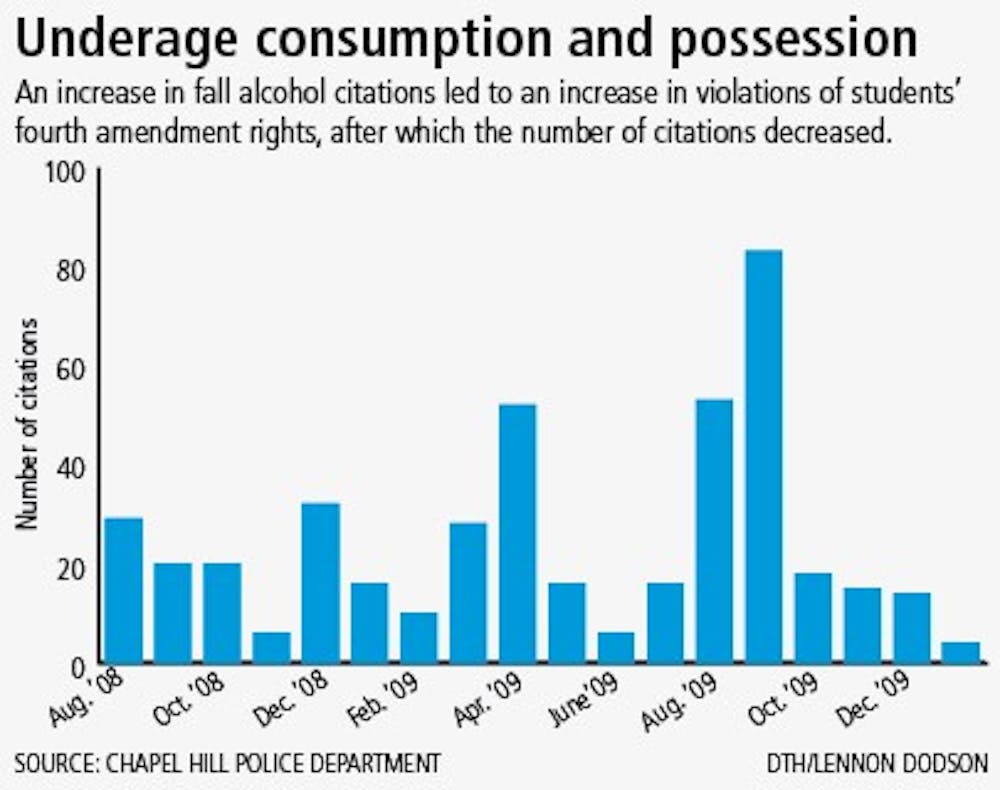

While the number of citations skyrocketed this fall, the consequences of the charges also became more weighty.

Taking a plea bargain, or deferred prosecution, in exchange for the charges later being expunged often doesn’t wipe the slate clean, said Dorothy Bernholz, an attorney at UNC’s Student Legal Services and Steve Bernholz’s wife.

An increasing number of employers and schools are asking applicants to list any charges expunged from their record, though state statues do not legally require applicants to answer that question, she said.

“It’s not uncommon for the police when they’re in the process of charging the student to say, ‘Don’t worry about this. It’s minor, and I’m sure it’ll be dismissed if you talk to the DA,” Steve Bernholz said.

“But expungement doesn’t really solve the problem these days.”

The decision to hire a lawyer, however, can be an expensive one.

The student charged at the McDade party said she took a bargain because her parents didn’t want to pay for an attorney without a guarantee the case would be dismissed.

“It’s purely punitive,” Dorothy Bernholz said. “It’s not an educational process.”

Contact the City Editor at citydesk@unc.edu.