Marvin Austin writhed in the thrill of victory as he stomped off the field at Kenan Stadium, convulsing with the emotion of North Carolina’s 33-24 win against Miami last November.

His dreadlocks snapped at the air, flicking drops of sweat toward the crowd pounding at the tunnel into the locker rooms. Spit flew as he howled at the bright lights, the TV cameras, the 58,000 fans.

“We’re The U! F--k them! We’re The U!”

Austin invoked the popular moniker of the Miami football program that dominated college football in the 1980s and 1990s. The program, despite its rampant scandal, personified swagger.

The U represented winning, unparalleled talent and NFL draft picks. That legacy — without the scandal — is one which Austin, UNC and coach Butch Davis want to recreate in Chapel Hill.

For the University and the athletic department, that legacy is important more for what it could bring: lucrative TV contracts, packed stadiums, potential donors and bigwigs in luxury boxes. In short, millions of dollars in revenue.

But UNC’s entrance into the arms race of college football could also bring with it the sting of a fruitless investment as the football powerhouses continue to rack up both wins and dollars.

The beginning

Coveting the huge profit margins of the major football conferences, the ACC entered into this race with a three-team expansion in 2003 – bringing in perennial football heavyweights Miami, Virginia Tech and Boston College.

The shift toward football left North Carolina with the option to sink millions into creating an elite football program and hope for a hefty payday in the future, or watch as the rest of the conference passed by.

North Carolina chose the former.

To generate revenue, though, the team first had to generate wins.

It started with hiring Davis, the coach who built Miami’s 2001 national championship team. He replaced John Bunting, who struggled in his final few seasons leading the Tar Heels.

“When the program is struggling, it’s hard to get people excited about buying some premium seating or giving to renovations,” athletic director Dick Baddour said. “But when we hired Butch, it was a strong statement.”

Davis’ hiring generated excitement, but he came at a price. Davis’ contract and incentives are worth $2 million annually, and he’s signed through 2014.

His resume and early success have jump-started the cycle the athletic department hopes will carry it to financial success.

After highly regarded recruiting classes and 16 wins in the last two years, donors opened their wallets to pay for several facility improvements.

First to be announced was the $25 million renovation of Kenan Stadium, then a $10 million sports medicine facility opening in 2010.

And finally, the New Kenan project adds three levels of luxury seating in the east end zone and a new student-athlete center. The project will cost an estimated $70 million to $85 million.

The combined investment is up to $132 million, coming mostly from private gifts.

Slow start

Despite the building projects, overall profits have been slow to arrive for both UNC and the ACC.

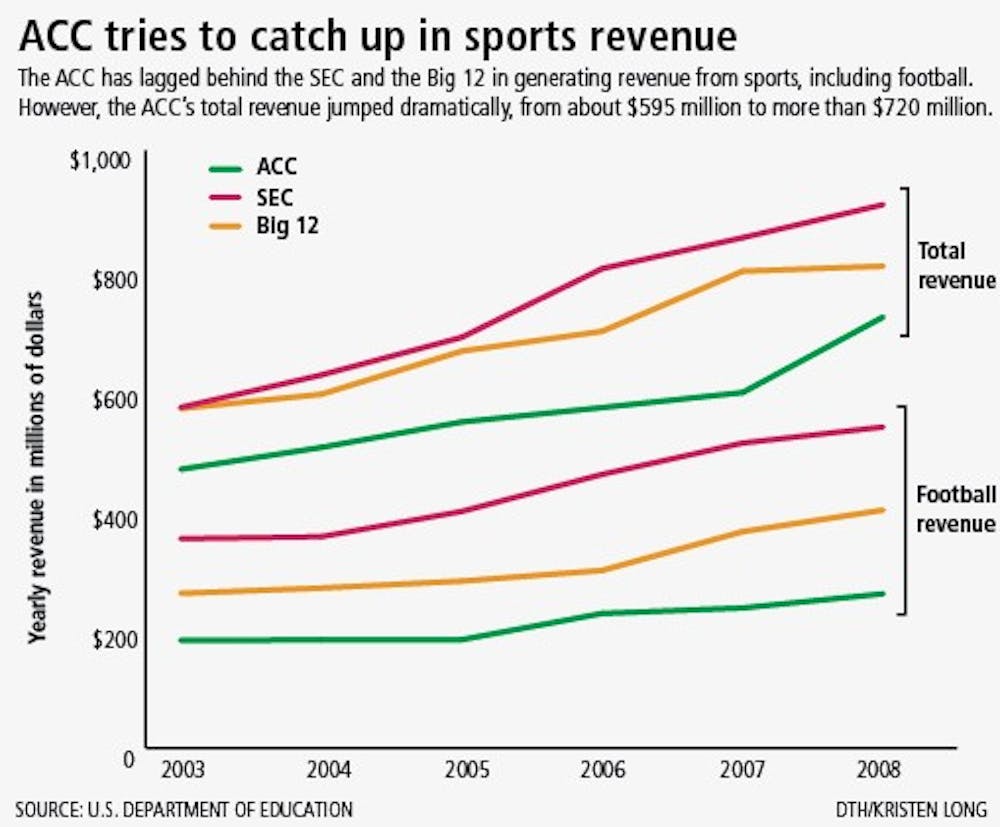

Since 2003, the first year after expansion, the ACC’s football revenue has grown from $180 million to $258 million last year. But in truth, the conference fell further behind the leaders.

The SEC reeled in $537 million in football revenue, and the Big 12 reported $398 million.

Baddour said he’s reserving judgment on the expansion until the new television contract negotiations in 2011.

“I think that the major impact of (expansion) is not yet known,” Baddour said. “And that will be how successful the conference is in negotiating the new television contracts.

“…We’ve seen some impact financially, but I think we’ll know better in a year, year-and-a-half.”

As a university, North Carolina is also struggling to keep pace. UNC’s athletic department reported $9 million in surplus from football. That’s still less than men’s basketball, which produced $12 million in 2008, and it’s a sum that’s dwarfed by other major football schools.

“It’s a challenge to keep up,” Baddour said. “What’s happening in football right now is mind-boggling. What’s happening on the salary side, we’ve got to be very mindful of that and work hard to see that we stay competitive.”

Keeping up with Texas

Still, UNC teeters between the haves and the have-nots in collegiate athletics.

Texas’ $138 million annual revenue almost doubles UNC’s $70 million, and UNC’s football program needs to bring in more money to keep the program in the black.

Profits like that generate an arms race in collegiate athletics as coach salaries skyrocket, facilities require $100 million investments and recruiting is uber-competitive.

The cycle of one-ups shows no signs of slowing or stopping. That trend will be central to the discussion of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics when it meets this spring.

The commission, which studies intercollegiate athletics in cooperation with the NCAA, already administered a survey of 119 presidents of Football Bowl Subdivison colleges. The consensus was that the current model for collegiate athletics was breaking the bank for many universities.

“You can never buy victory,” said Hodding Carter III, UNC professor and member of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. “You get into an arms race, and everybody else is out there buying victory.”

Contact the Sports Editor at sports@unc.edu.

UNC spends to build up football franchise

DTH/Kristen Long