The power of PlayMakers Repertory Company’s production of August Wilson’s “Fences” is its biting realism.

Director Seret Scott’s cast portrays a socially segregated 1950s Pittsburgh, where living between paydays wears away at old dreams and diminishes the promise of a hopeful future.

As the play advances, a fence is slowly built around the protagonists’ home — and while keeping worldly hardships out, the barrier also keeps troubles captured within.

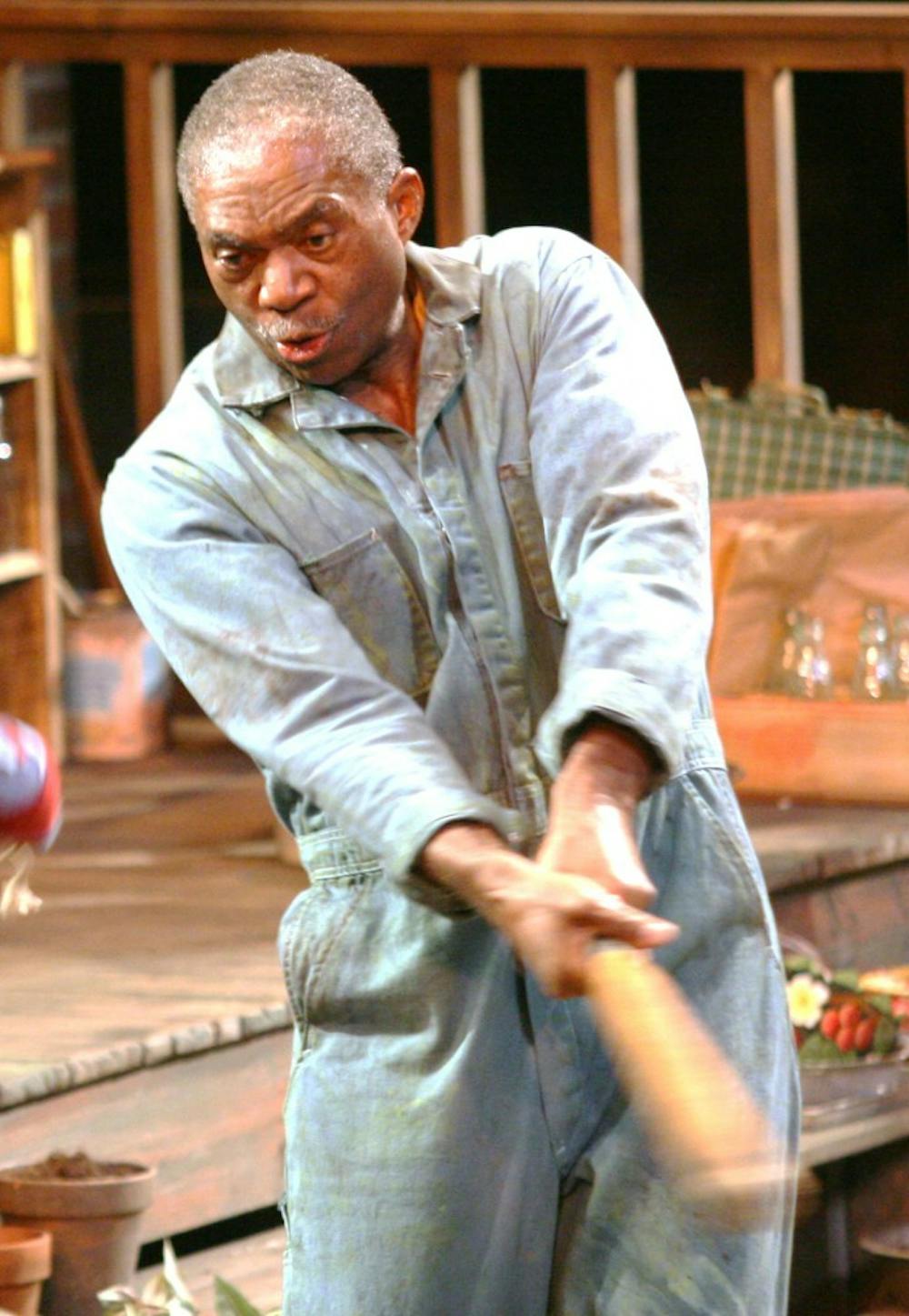

At the play’s center is Troy Maxson, played by Charlie Robinson. As a former Negro League ball player drowning in a culture of limited opportunities, Robinson is brilliantly bitter.

Whether spouting sexual jokes or weaving nostalgic stories of his difficult past, Robinson buys — and hence owns — the audience’s attention from start to finish of the two hour-plus play.

His unexpected eruptions of frenzied wrath, with bulging neck veins and steely eyes, drive the show.

But Robinson finds his biggest power in a tender scene on a darkened stage. While cradling his newborn daughter, Robinson sings the blues.

Countering the precarious Troy is his wife Rose, played by Kathryn Hunter-Williams. Hunter-Williams is an equalizer — without the actress, a surplus of emotional male tirades would overwhelm.

But when the steadfast wife of 18 years learns of her husband’s affair, her deadpan defense allows the performer to dive into soulful, groaning retorts, receiving shouts of encouragement from women in the opening night’s audience.