How substantial or merely symbolic those raises turn out to be is for the deans and department chairmen to decide, said Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Bruce Carney, who will give them the leeway to restore instructional losses and provide merit-based raises as they see fit.

“I’d like to show them that we have turned a corner,” he said.

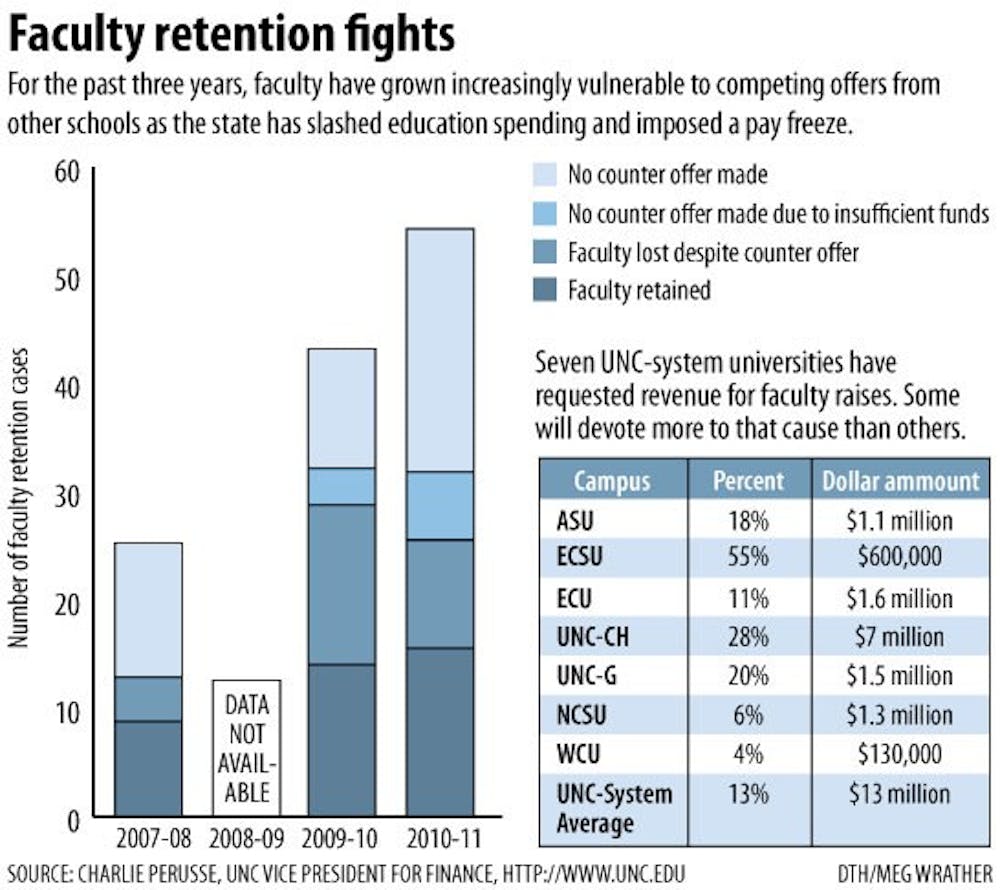

That will be possible only if the state legislature agrees to grant the UNC system an exception to the pay freeze, which academics regard as sound educational and economic policy. Retaining new faculty members, administrators said, is more cost-effective than hiring new ones — though it remains unclear whether legislators will agree.

“If we don’t get the pay raise, we’ll continue to work on the instructional side and the Academic Plan,” Carney said. “But I want, damn it, I want the pay raise.”

Holding on

Together, the tuition proposals offered by Carney and Ross underscore a balancing act between maintaining access to higher education and upholding the academic quality that attracts students in the first place. To that end, Carney frequently turned to low faculty morale and the need to raise salaries during the tenuous tuition debate last fall.

He cited top professors as the lifeblood of campus, the ones who draw students — and the ones UNC-CH has been hemorrhaging of late.

In addition to the counteroffers, 48 preemptive offers were made to retain faculty members who did not have an outside offer in hand, but who were judged by their dean to be at risk for outside recruitment.

“Once the offer is in their hand, the chances of them going is not low,” said Dr. Ron Strauss, executive vice provost. “That’s when we say, ‘Please don’t get on the airplane.’”

To make those counter or preemptive offers, schools and departments have looked to the endowment, trust funds and overhead funds, along with a UNC-system faculty recruitment and retention fund.

Since 2006, the system’s campuses have tapped into that fund for nearly $10 million worth of hiring and retaining prized faculty, $1.7 million of which has been spent in Chapel Hill.

“I scarfed that up,” Carney said.

That fund has been drained to $38,071, said Charlie Perusse, vice president for finance for the UNC system, though administrators hope to replenish it with $5 million from tuition.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Faculty are entertaining offers not only from deep-pocketed private schools, but from rival public universities as well. As several administrators acknowledged, no one has been quite as aggressive as the University of Michigan, which endured similar financial duress only a few years ago to emerge with more of a “state-assisted model” than a state-supported model, granting it more flexibility, said history department chairman Lloyd Kramer.

“The word is out that times are tough. They’re on the prowl,” said Coble, who’s currently fending off Michigan’s attempts to woo a member of her department.

International universities have also stepped up their efforts. Between April 2010 and May 2011, three professors left for universities overseas. “We’re very well-regarded in the international rankings,” Carney said. “That’s a source of pride, but it also paints a big bull’s-eye on us.”

‘A double hit’

Last summer, Barbara Rimer found herself alone in a room with more than 30 of her fellow deans. As dean of the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, Rimer was in Montreal for the Association of Schools of Public Health’s annual deans’ retreat when someone asked the question: Who isn’t giving pay raises this year?

Rimer’s hand was the only one that shot up. “I think it really puts us at risk,” she said. “It sends a message to other schools of public health: Come steal our faculty.”

Many of those vulnerable faculty include principal investigators whose salaries derive mostly from research grants. Oftentimes, the grants allow for a raise — but the state’s pay freeze has prevented them from taking it.

“It’s infuriating, totally infuriating,” Strauss said. “We want to let them use the raises written into their grant budgets.”

When the researchers leave UNC with their grants in tow, Rimer said it’s a “double hit” because the schools lack the funds to hire a replacement. And when UNC does recruit a high-caliber researcher, it often takes as much as $500,000 in lab start-up costs to do so.

’A chicken and egg thing’

Too often, Coble said, she lies awake at night, thinking tactically about how to stretch what few dollars her department has.

Too often, she has to say, “No.”

“At my age, it’s pushing me to early retirement. I have two more years as chairwoman of this department. Under similar budget circumstances, I would not agree to chair again,” she said.

“For a great university, you don’t need the grand buildings — you need faculty and students,” she added. “It’s a chicken and egg thing: If you build a great faculty, students will come. If you have great students but faculty with no resources to teach them, they’ll find them elsewhere.”

Contact the University Editor at university@dailytarheel.com.