Nearly 50 years ago, Chapel Hill was a town restless with civil rights conflict.

During a series of demonstrations for racial equality in January 1964, roughly 239 people were arrested as the tension to integrate built.

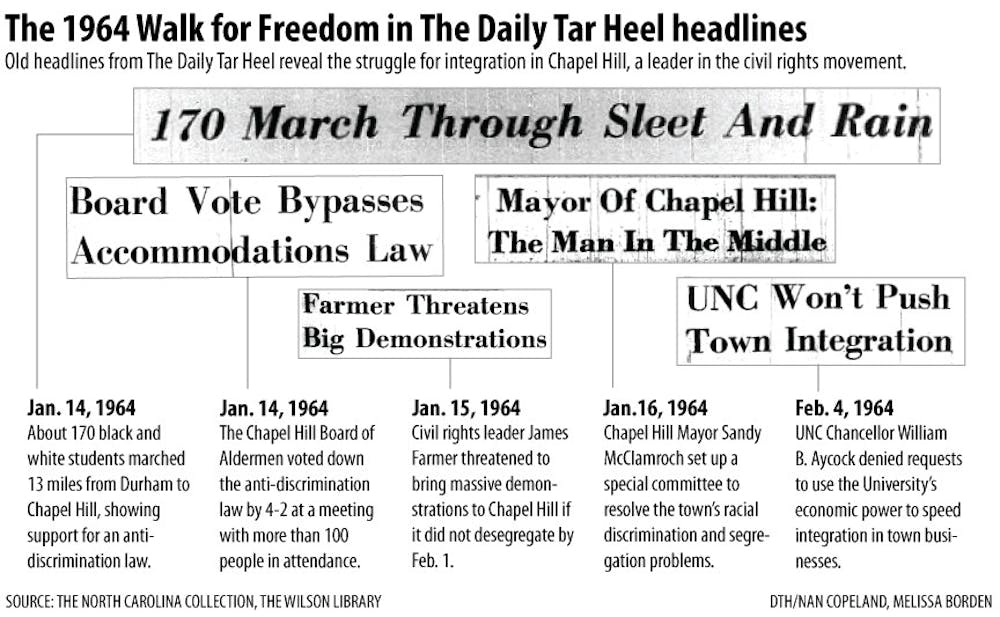

On Jan. 12, 1964, civil rights activists marched 13 miles in freezing rain from Durham to Chapel Hill to demonstrate support for an anti-discrimination ordinance.

The next day, the Chapel Hill Board of Aldermen voted 4-2 against the ordinance — which would have outlawed segregation in the town — and instead created a committee tasked with solving problems of race discrimination and segregation.

Chapel Hill was seen as a state leader for civil rights — making the board’s decision especially hard for civil rights activists.

The march brought together about 170 students from North Carolina Central University, Duke University and UNC and attracted national attention from newspapers and civil rights activists.

James Farmer, co-founder and first national director of the Congress of Racial Equality, traveled to Chapel Hill and spoke to marchers on Jan. 12. He threatened to focus national efforts on Chapel Hill if the town did not integrate by Feb. 1.

“Chapel Hill was spotlighted all over the whole country because of what was going on with the demonstrations,” said Sandy McClamroch, who served as mayor of Chapel Hill from 1961 to 1969.

“All the big movements were taking use of Chapel Hill’s problems for their national publicity. It was a very important time for the town and the University.”