She didn’t mean to make history — she only wanted to study it.

“I was born in the 1970s, so I generally don’t go down for being first anything,” Blair Kelley said.

Yet she recently became the first black woman to be tenured in N.C. State University’s history department after being hired on the tenure track in 2002.

“My department has a pretty good reputation of really wonderful women faculty, but we’re the minority, as I think we are in all kinds of places,” she said.

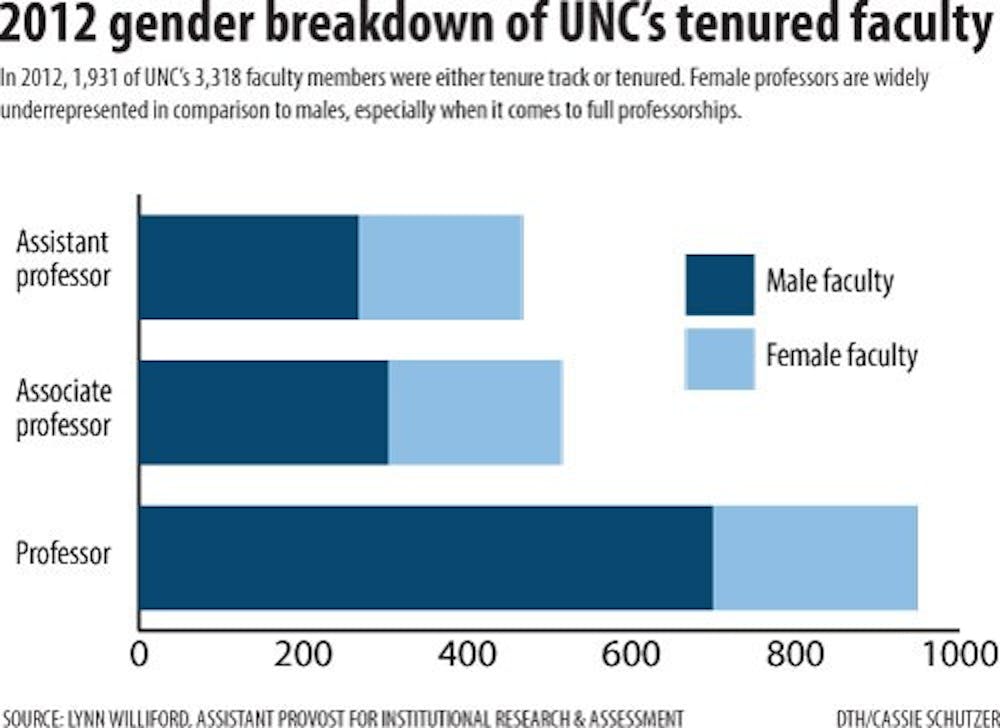

This underrepresentation of females, as well as racial minorities, in tenured positions is not confined to Raleigh — it is a national issue, and it is one that UNC is also dealing with. Instead, women are overrepresented in fixed-term positions.

“In general, we have seen that as the academic profession has seen growth of contingent faculty — that those positions tend to be more occupied by women faculty,” said Anita Levy, associate secretary of the American Association of University Professors’ Department of Academic Freedom, Tenure and Governance.

In the fall of 2013, 31 percent of UNC’s tenured faculty consisted of women, as did 43 percent of tenure track faculty — on the other hand, women made up 56 percent of UNC’s fixed-term faculty.

Associate research professor Sue Tolleson-Rinehart said while one can still rise to full professorship as a fixed-term faculty member, they don’t have the long-term security and freedom that comes with tenure.

“Probably the biggest difference is the sense of security — unless the University collapses or unless I’m out there having sex with animals on the street,” she said. “In some ways a tenured academic position is one of the real bastions of real job security left.”