“It’s gonna be hell every day. It’s gonna be hard and it’s gonna suck,” Buckland said, “And the first two weeks are absolutely awful because you’re stuck in a brace, you can’t even bend your leg.

“Breaking up the scar tissue is absolutely terrible, and then all you can do is like a straight leg raise, but that straight leg raise absolutely kills, and it hurts, and it’s mentally one of the hardest parts because you’re like ‘I’m lifting a two-pound weight with my leg, and I’m literally struggling trying to do that.”

She grits her teeth in determination. It’s a task that appears relatively simple: a one-legged squat with 10-pound dumbbells in each hand. But on a reconstructed knee it’s a grueling exercise, one that has Buckland’s face shining with the first hints of perspiration. Her knee wobbles with every rep, and when she finishes it’s apparent that she struggled. But she succeeded. The rehab is hell, but it isn’t the worst part. The worst part is when she’s doing nothing at all. When she’s nothing but a spectator at practice.

“I really wish I could give you one word to describe it, but it just flat out sucks. It’s easier on days when they’re doing really well, because I know, I’m confident and I believe in them that they can go out and succeed every day,” Buckland said.

Other days, when practice isn’t running so smoothly, it makes sitting on the sideline even harder.

“I feel like if I could be out there maybe I could help make a difference. It’s just hard knowing what kind of difference you can make from the sideline.”

The third time for Buckland has been anything but a charm. The frustration is obvious. It’s understandable. She felt the magic of playing for UNC from the first moment she set foot on the court. And this injury takes all of that away from her and dangles it just out of reach. It’s like she’s been able to test drive her dream car, and now she can only stare at it as it sits in the garage. But she’s accepted her circumstances, even though her misfortune is almost incomprehensible.

“I just had to learn to be patient, and to know that God has a plan out there,” Buckland said. “Might not know it right now, might not be visible right now, but it is out there.

“And now it’s just kinda like knowing that it’s all for a greater purpose … taking on that leadership role as like a junior type thing, and being more vocal and voicing what I think more.”

In her workout shorts the scars are out in the open, faint lines that serve as a reminder of what she’s been through before. The one on her right knee is still somewhat scabbed over, the freshest wound, the one that’s still healing. One minute she holds a medicine ball and does walking lunges across the room, the next she’s on a machine doing leg presses. She’s up to 100 pounds on the leg press machine, from 80 pounds last week.

“Looking good, superstar,” UNC’s head athletic trainer for women’s basketball Nicole Alexander says as Buckland completes a set of lunges. This elicits a smile from Buckland, the first since she’s started her routine. Alexander says that her job is more than overseeing the rehab, it’s just as important for her to keep the athletes laughing and smiling throughout the process.

She watches Buckland’s every move like a hawk, criticizing each small wobble of her knee. But with such a long rehab process, Alexander stresses that it’s about the small successes, the baby steps. She says that’s the hardest part of her job, forcing talented athletes to focus on little moments of progress, because athletes do not like baby steps.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Senior hurdler Devon Carter has been down a similar road himself, recently recovering from a partially torn hamstring. He says the beginning is the worst part, the time when an athlete in excellent shape has to dumb his workout regimen down to simple stretches.

“The part I don’t like about rehab is when I have to do the little things, the baby steps to get to a point where I’m actually getting stronger and getting better,” Carter said. “I don’t like going through those little things.”

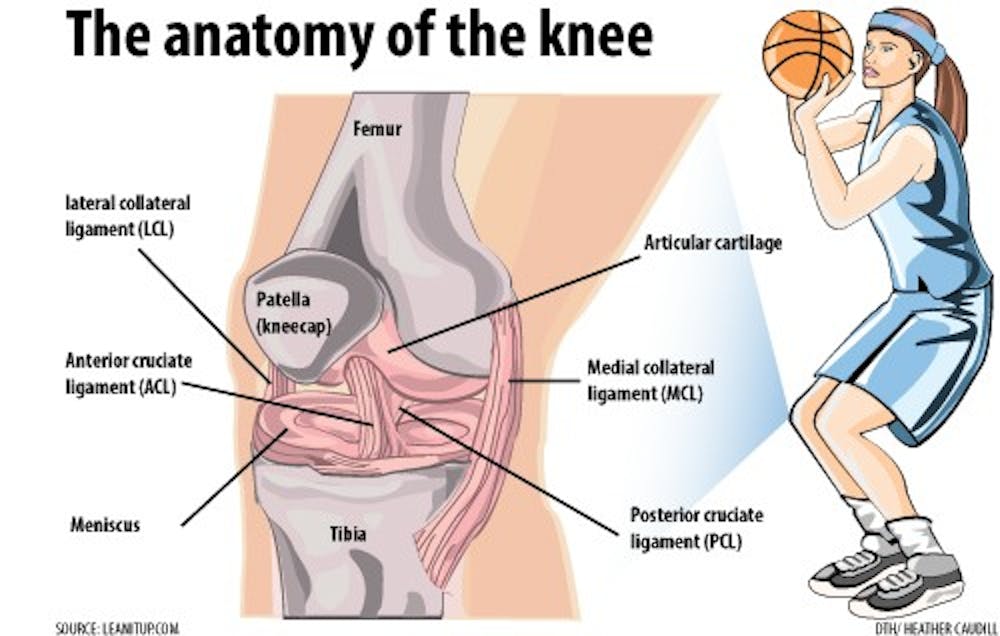

The ACL recovery process takes months before an athlete can be officially cleared to participate. But even though they’re medically cleared, they won’t be the same until they can get their confidence back.

Confidence is a tricky thing, it can’t be medically fixed, it has to be repaired in a trial by fire. Buckland says it takes getting back on the court and going full speed before she can really be back.

“The first time you’re confident enough to dive on the floor after a loose ball and the first time you’re confident enough to drive into the basket — there’s gonna be full-on contact — those are the moments when you’re like, ‘OK, I can do this. I can be confident enough in myself to be a player like I used to be.’”

Buckland can finally start running sometime in the next week or two, and take another baby step toward full recovery. She hopes to be back on the court at full strength sometime over the summer. In the meantime, UNC takes the court this weekend in the ACC tournament. And with each game UNC plays, Buckland will once again assume her spot orchestrating warm up drills at the top of the key. Ball in hand. Waiting on the day when she can take the shot.

sports@dailytarheel.com