Nate Fisher, a fifth year middle grades major, said he feels society often steers males away from teaching.

“There’s the gender stereotypes of men should be the primary breadwinner and you’re not getting rich teaching, that’s for sure,” he said.

Fisher said the portrayal of teachers as women in media creates the impression that education is a woman’s profession.

“Women are thought of as more nurturing for children,” he said. “I think that partially accounts for why you see that major variance.”

The gender disparity in teaching dates back to the 1900s when young women began attending school in increasing numbers, McDiarmid said. The main shift took place in World War II when men were sent to war, and women took over the classroom.

“The demographic that we have today is not all that different than it was 60 years ago,” he said.

The problem has gotten worse in recent years, McDiarmid said.

“As someone who’s a male teacher, I’m very saddened that there aren’t more males going into teaching,” McDiarmid said. “I would love to turn that around but I don’t know quite how you turn it around to be honest.”

The school does what it can to recruit males into the program by encouraging male education faculty to be visible on campus. The school hasn’t done much in the past to recruit male students out of the education minor and into the education major, he said, but they are going to start, McDiarmid said.

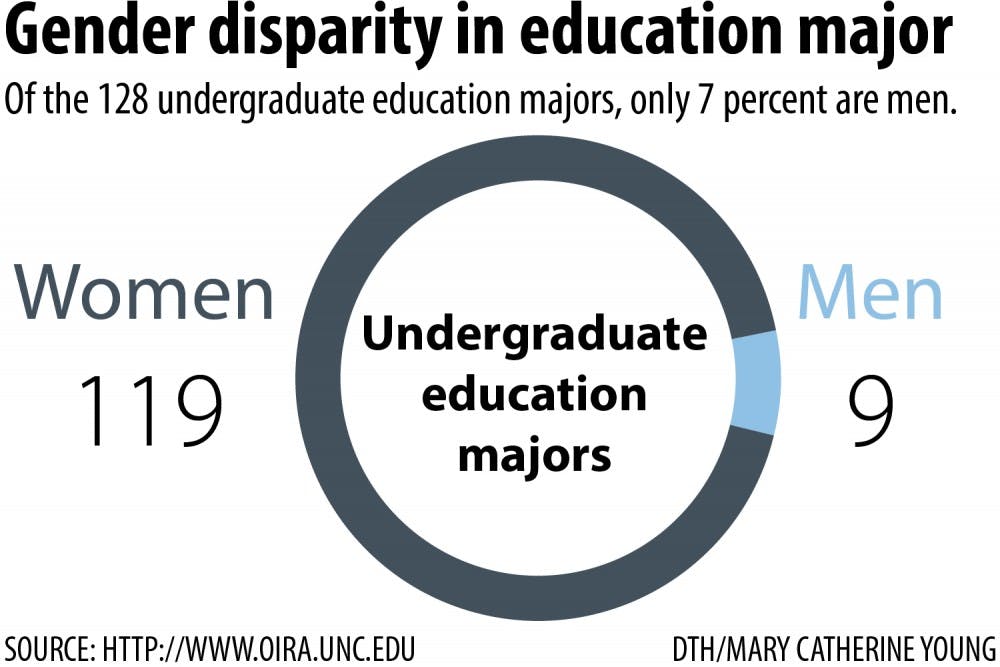

Gender gap in the field

The gender disparity in the School of Education doesn’t disappear at graduation.

“Those are the very pools that we draw upon to recruit candidates,” said Mary Gunderson, coordinator of teacher recruitment and support for Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Gunderson said she has hired 181 teachers for the district this year — only 43 were men.

“What you see at UNC is very typical of what you see in the state and nationally,” she said.

Gunderson said she tends to see more male teachers in content areas like science and math, and very few in elementary grades.

“Absolutely it has implications,” she said. “It means a male child could go all the way through elementary school and never have a male teacher.”

Gunderson said she would like the teaching population of her district to be representative of the student population, and with the gender disparity in teaching, it’s far from representative.

Adam Holland, now an investigator with the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, worked as a kindergarten teacher at a school with only one other male teacher in the building.

“For me it was an adjustment,” he said. “When you’re in the minority, you’re always cognizant of that fact.”

Holland said he experienced subtle discrepancies as a male kindergarten teacher, including expectations that he would dress more nicely than his female colleagues.

Holland was also cautioned as a man working with young children to always have another teacher around, partially out of fear of lawsuits, he said.

“I was always told by my professors and by administrators that I needed to be very careful,” he said. “That kind of thing can make you wary of going into a profession.”

Holland said he’s known males who start out to become teachers to reroute from education because of the gender disparity. It’s difficult to enter a field that doesn’t feel welcoming toward you, he said.

A different route

It’s common at UNC for males to pursue an education minor because they are interested in larger policy issues, which McDiarmid said somewhat evens out the gender distribution among education minor students.

William Brown, a senior history major and education minor, said the gender disparity is still apparent in the education minor.

“If there’s only two dudes in the class, you kind of lose out on the guy’s perspective on things as well,” he said.

Brown said he has taken three education classes through his minor and each time, males have been in the severe minority.

The only other male in Brown’s education class this semester is fellow senior, history major and education minor Dylan Kite.

Kite said he chose an education minor because he didn’t decide on teaching until later in his undergraduate career. He said he’s not surprised so few men major in education.

“It’s not surprising but I wish it were different,” he said. “You just don’t meet that many guys in education.”

McDiarmid said UNC’s Baccalaureate Education in Science and Teaching program boasts a larger percentage of males than the traditional education major.

UNC-BEST provides science, technology, engineering and math majors with education licensing opportunities.

There are 53 students currently enrolled in the UNC-BEST program, 12 of whom are male. He said that 23 percent figure is a slight improvement from the seven percent of education majors, McDiarmid said.

McDiarmid said he didn’t think the BEST Program was pulling males from the traditional education major though.

“They’re two different populations,” he said. “The folks who go into the STEM program are very serious about their subject matter in science or mathematics.”

UNC-BEST students are more driven by a passion for the subject matter, while education majors are more driven by a desire to teach, McDiarmid said.

Self-perpetuating cycle

McDiarmid said a small percentage of male teachers in elementary schools can serve as a self-perpetuating cycle.

“If you don’t have male teachers as a boy, you don’t think of that as a possible profession for you, and it goes on and on,” he said.

McDiarmid said he has felt for a long time that the gender distribution in the school of education is a problem that needs to be addressed.

“There’s something terribly wrong with this,” he said. “There’s now a heightened awareness ... of the need to do something about this.”

university@dailytarheel.com