From Columbia University to Florida State University, the mishandling of sexual assault is well-documented at colleges, which begs the question of how appropriate it is for a college to investigate a felony crime.

Title IX requires colleges to protect students from sex-based discrimination — which has led to colleges investigating and sanctioning sexual assault cases.

But some college rape cases aren’t prosecuted at all by law enforcement.

In college rape cases, alcohol often impacts questioning, evidence collection and witnesses’ testimony. Police play an integral role in whether a case can make it to court and whether it can render the rare guilty verdict.

Reports often start with Chapel Hill Police or UNC’s Department of Public Safety.

Tracey Vitchers, spokeswoman for Students Active for Ending Rape, said many campus and local police lack the training to properly investigate sexual assault.

“We heard of a girl who was raped, went to campus security and they told her to bring her clothing to local police. She texted a friend and asked her to bring the clothes — it had changed hands and the clothes became inadmissible in a court of law,” she said.

Randy Young, a spokesman for DPS, said campus police began offering intensive sexual assault training in 2012, the same year that criticism over UNC’s handling of sexual assault became public. Now, all officers are trained on how to handle these cases, he said.

A victim’s cooperation

In many domestic violence and rape cases, police don’t conduct a full investigation, said Amily McCool, who works with the N.C. Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

“Law enforcement relies too heavily on that the victim will testify,” she said, saying the police often rely on the victim’s report, which can be enough to charge the suspect.

If a victim decides not to participate in the prosecution of the case — which is common with domestic violence and sexual assault cases — then a significant portion of the evidence is lost and the district attorney’s case could be lost.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“If law enforcement does a thorough investigation, if they take pictures of the scene, talk to witnesses, get the 911 call — you still have a case,” she said. “We need to be shifting our treatment of the case.”

Between 2009 and 2014, a similar DTH analysis found the Orange County District Attorney’s Office declined to prosecute 11 percent of cases forwarded to its office from the Chapel Hill Police Department.

Between Jan. 1, 2009, and Dec. 31, 2013, 18 sex offenses reported to DPS closed because the “victim refused to cooperate,” a term which means that the reporting party did not want to proceed with an investigation. In total, there were 44 sex offenses reported to DPS in four years, according to records obtained by the DTH.

Every DPS case in which the victim did not cooperate is listed as “closed” or “cleared,” but no arrests were made in those cases.

Chapel Hill Police require all officers to undergo an eight-hour, victim-centered training, said Sabrina Garcia, a crisis counselor for Chapel Hill Police who also trains DPS officers.

“Law enforcement has focused on the victim and the credibility of the victim — it’s important, that’s not to be negated,” she said. “What we’ve done less of is doing a good investigation in regards to the alleged suspect.”

For district attorneys who receive sexual assault cases, the challenge can be encapsulated in one word, said Orange County Assistant District Attorney Michelle Hamilton.

“Alcohol, alcohol, alcohol — honestly,” she said. “Alcohol. Those are the cases that frustrate the heck out of me. It makes it so hard, under North Carolina law, when everybody is inebriated.”

Hamilton said she couldn’t think of a college case that didn’t involve alcohol.

“That’s my barrier,” she said. “We have to prove that there was not consent, or it was by force against that person’s will, or that person was unconscious.”

When Hamilton evaluates a case, she considers whether alcohol will make certain elements of the case impossible to prove. Then she tells her client the line of questioning will be uncomfortable.

“One time a young lady said she took her shoes off and went to the back room. I said, ‘Well how did you get to the back room? Was it cold on the floor? Were you on your back? Was it hot in there or cold in there?’ In those cases, everything matters.”

Another element Hamilton must prove is that the victim resisted the advance — and it has to be enough resistance that the rapist overcomes the victim’s actions.

“Some people, admittedly, are absolutely terrified,” she said. “They freeze. There’s a school of thought that women freeze and don’t want to get hurt. It’s a survival tactic. There are some cases where she says, ‘I pushed him away,’ and I’ll say, ‘Fabulous!’ and take it.”

Punishing assailants

Juries and justices sometimes understand that victims can’t outright resist an advance, whether it’s due to a history of abuse or a visible weapon. But overall, this standard is murky, Hamilton said.

“That’s where the law doesn’t understand that that’s what sexual assault looks like,” she said. “Do I think that will change? I don’t know.”

McCool said the challenge with punishing assailants isn’t only up to people with law degrees — it needs to be a societal change.

“Even if this goes to district court … a defendant is going to appeal and have the case heard in front of a jury. This is 12 people from the community who have their own perceptions and misperceptions about rape.

“How do we educate the public so we have more informed juries?”

Vitchers said not every student feels comfortable with law enforcement — and universities’ adjudication processes are supposed to represent an alternative.

“Many survivors don’t know or trust law enforcement and their treatment of survivors — many don’t want to go through one, two or three criminal proceedings. It’s more supportive to go through their schools.”

But colleges, including UNC, also have their own failings.

UNC student Landen Gambill, who filed a Title IX complaint in 2013 alleging the University mishandled her sexual assault case, said not every survivor wants to turn to the courts.

“So few cases actually end up going to trial and end up in convictions because police and prosecutors for whatever reason — whether it be because of institutional sexism or the law not being good enough. There’s not a good outlook for justice for folks,” she said.

“When your concern is your immediate safety and immediate health, it’s a better option in some ways — if the university were able to hear these cases and get the perpetrator out of your vicinity. That would be a good option for a lot of survivors.”

Colleges’ handling

When survivors come to Cassidy Johnson for counseling, she never tells them what to do. As UNC’s gender violence services coordinator, she presents them with options.

Due to confidentiality reasons, she can’t say whether a survivor has ever expressed concern with reporting due to the publicity surrounding UNC’s handling of sexual assault. But holding UNC accountable is important, she said.

“There’s like a sense of distrust in a lot of ways … More in the sense of confusion and not knowing what could happen — it could keep people from coming forward,” Johnson said.

Survivors have anxiety about whether or not their case is a “good case” — meaning whether or not it is viable for prosecution and punishment — compared to cases publicized in the news, Johnson said.

“They’re terrified the person is going to get away with it,” she said. “When you read about a survivor who has tried to report these crimes to multiple offices, it can be really disappointing and confusing.”

When UNC students pursue a report through the University, it can go through several stages — reporting, the investigation, the hearing process and appeals.

After investigators make a preliminary finding, which can be appealed or accepted by the victim and the accused, the cases can then go to a student grievance hearing, which consists of three trained panelists.

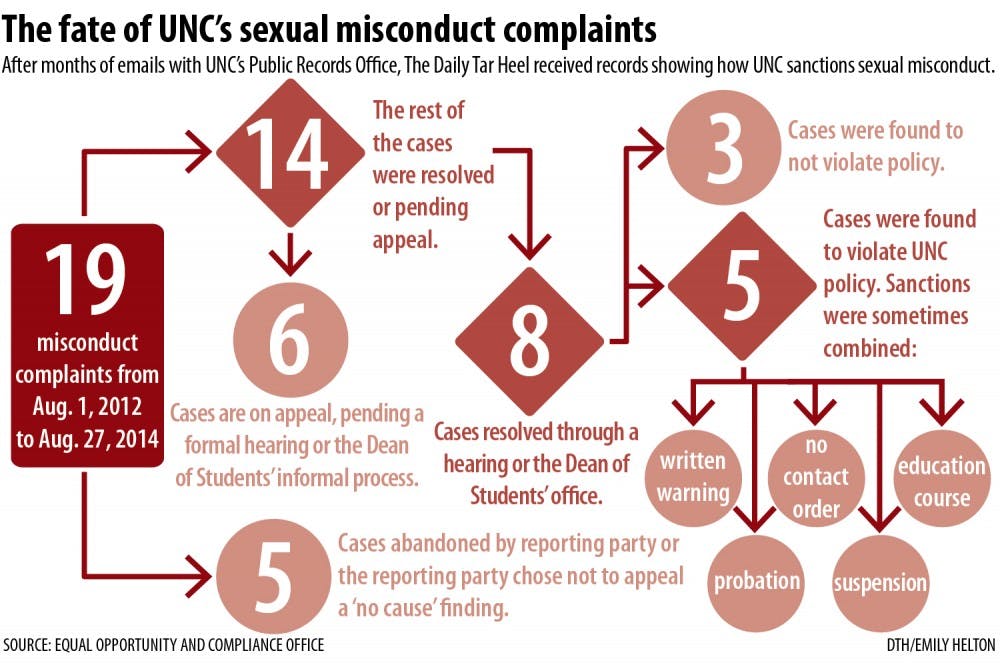

The same data that showed no students were expelled after violating the University’s sexual misconduct policy shows that in the two years before UNC’s new policy was unveiled, 19 sexual misconduct complaints were filed. Because the reporting party abandoned the complaint or chose not to appeal a “no cause” finding at the investigation stage, five cases of the 19 did not move forward. Of the 14 remaining complaints, eight were resolved through a formal hearing or the Dean of Students’ office. Of the eight resolved cases, five violated the policy.

Six remaining cases are on appeal, pending formal hearing or the informal process. They will be heard under the rules and procedures of the 2012 policy rather than the new policy unveiled in August 2014.

A hard case to mount

UNC law professor Bernard Burk, who currently serves as a panelist, said adjudicating cases that reach this stage is difficult because the two parties often fundamentally disagree about what happened.

Confidentiality means he can’t say how often a student is found to violate UNC’s sexual assault policies, Burk said.

The evidence differs by case: sometimes the parties’ don’t have a clear memory of what happened, in other cases there is medical evidence or witnesses, he said.

“The problem is that in a lot of the situations, figuring out what happened is terrifically hard,” Burk said.

The panel uses a lower standard of evidence — a preponderance of evidence — which means victims have to prove a policy violation happened “more likely than not.” Burk said this standard couldn’t be applied to the criminal justice system because of the seriousness of the penalties in addition to it changing constitutional standards.

‘Breaking the law’

Sen. Earline Parmon, D-Forsyth, said she hopes the N.C. General Assembly will take on campus sexual assault during its next session, through a special committee or legislation.

“It is something that we must address in terms of protecting the victim, in terms of ensuring they get all their rights and can pursue criminal charges … (making) sure the perpetrators are caught and prosecuted,” she said.

Presented with UNC’s sanctioning data, Gambill said UNC is too concerned with its reputation but needs prioritize student safety.

“Colleges are legally required to investigate these cases,” Gambill said. “There’s no room to argue about that. When colleges are failing to properly investigate these cases and failing to punish and expel rapists, they’re breaking the law.”

Universities have a role in adjudicating sexual assault, Burk said.

“Sex is a deeply fraught and complicated set of ideas in our culture,” he said.

“The fact of the matter is that at the beginning of any one of these processes we don’t know what happened and we have to hear what happened. What we really need to do is find a process that convicts only guilty people. It’s very difficult to do.”

university@dailytarheel.com