He lifted his arm to the sky and tucked his thumb into the crevice on the palm of his hand. And then, as if it were choreographed, the crowd of light blue shot to its feet, rising in sync with Ford’s now-outstretched fingers.

“You don’t see ‘The Four Corners’ anymore,” Ford said on Sunday. “They outlawed that, but I see his footprint on a lot of the plays and defenses that we see today.”

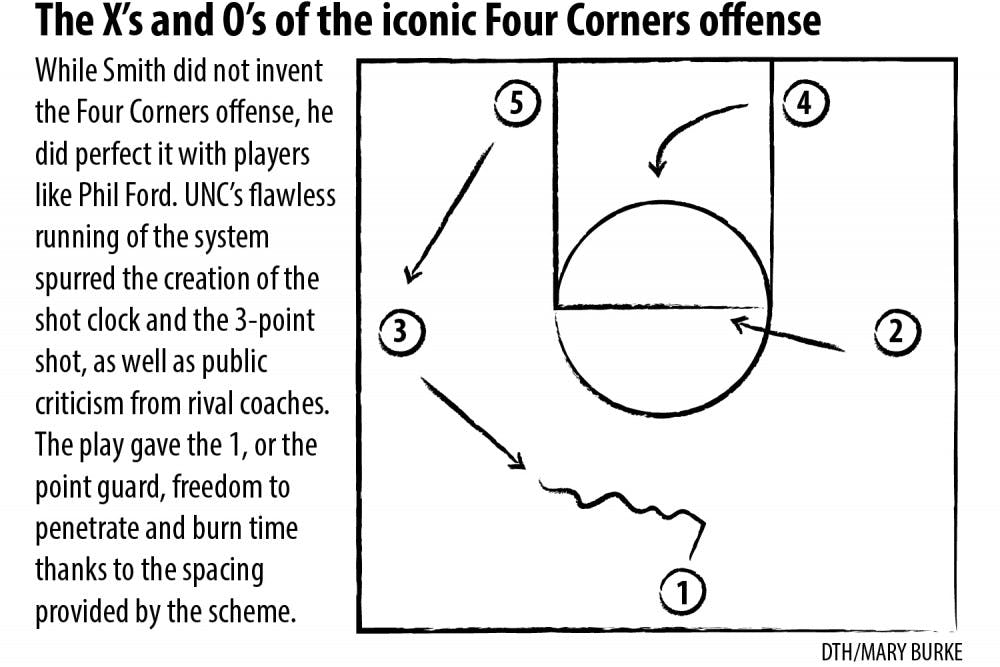

Strategically, the four corner offense was difficult to master. Four players spread out on one half of the court, forming a near-perfect square. They were outlet passers and safety valves — they were the four corners.

But in the center of this stagnant strategy was one ever-moving cog. At one point, that cog was Ford. By the time Smith finally led the Tar Heels to a national championship in 1981-82, Ford had been replaced by another facilitator: Jimmy Black.

But whatever the name on the back of the jersey, the role was always the same. The point guard was the primary ball handler, weaving in and out of the square. His job was to hold onto the ball for as long as he could by himself, only dumping it off to a corner at the very last moment. Then, he took back the ball.

The process repeated.

At times, it was nothing more than a game of one-on-one, the eight other bodies serving as cones on an otherwise open court. At other times, it was only that Smith taught his teams to play keep-away. And it worked.

That was never clearer than in the 1982 ACC championship game against Ralph Sampson and Virginia. Up a point with 7:34 to play in an era before the shot clock existed, the Tar Heels held the ball for seven minutes and six seconds to preserve their eventual 47-45 win.

But it didn’t last.

“One of the greatest compliments that I can give Coach Smith is that he changes as the game changes,” said North Carolina women’s basketball coach Sylvia Hatchell. “When the shot clock took away his four corners, he adjusted.”

Smith’s creation was next-to-impossible to stop on the court. But off the floor was a different matter.

During the 1985-86 season, college basketball implemented a 45 second shot clock that buried “The Four Corners” for good. The days of holding the ball for minutes on end were gone. It was no longer possible to pass the rock until the clock read zero.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Smith’s legacy is more than one system, even if that was where it all began. Smith’s legacy mirrored his coaching career: an ever-changing, evolving collaboration of moments that collectively tell a story — the story of a coach, the story of a man.

“He’ll be on the Mount Rushmore of college basketball, without a question. Not only his legacy as a winner and a champion but as a champion of social justice off the floor — as an innovator of the game,” said Jay Bilas, an ESPN analyst and former Duke basketball player. “There are so many things that he originated in the game of basketball. How many people can you say that about? Everyone that coaches now — that plays now — is doing something that Dean Smith innovated in some way.”

Maybe it’s clapping as a teammate comes out of the game. Maybe it’s “pointing the passer” after a made bucket. Maybe it’s just throwing a finger in the air — not four, only one — to signal that a player is tired.

It’s the little things in the game that Smith brought to the forefront, the signals and signs that young boys grow up mimicking. His thoughts, those moments of brilliance, were brought to life through his players and assistants every day on the job.

But more impressively than his coaching, better than anything he accomplished in the realm of basketball, Smith stressed the little people in his daily routine. Be it the men guarding the tunnel inside the Smith Center or the assorted masses who sent him letters, Smith always went out of his way to appreciate other people.

He always went out of his way to point the passer.

“Coach Smith has a legacy that touched basketball and will be around forever,” said Roy Williams, the current head coach at North Carolina. “You know, the little things like huddling at the free throw line, changing defenses, guys clapping when guys come off the bench — all those kinds of things. But one of the ones that I’ve always admired the most was pointing at the guy that made the pass.

“People will be doing things that they have no idea came from Dean Smith, but they’ll be doing it because it’s been passed down from coaches to coaches, players to players.”

Pointing the passer — it’s as easy as holding up four fingers.

sports@dailytarheel.com