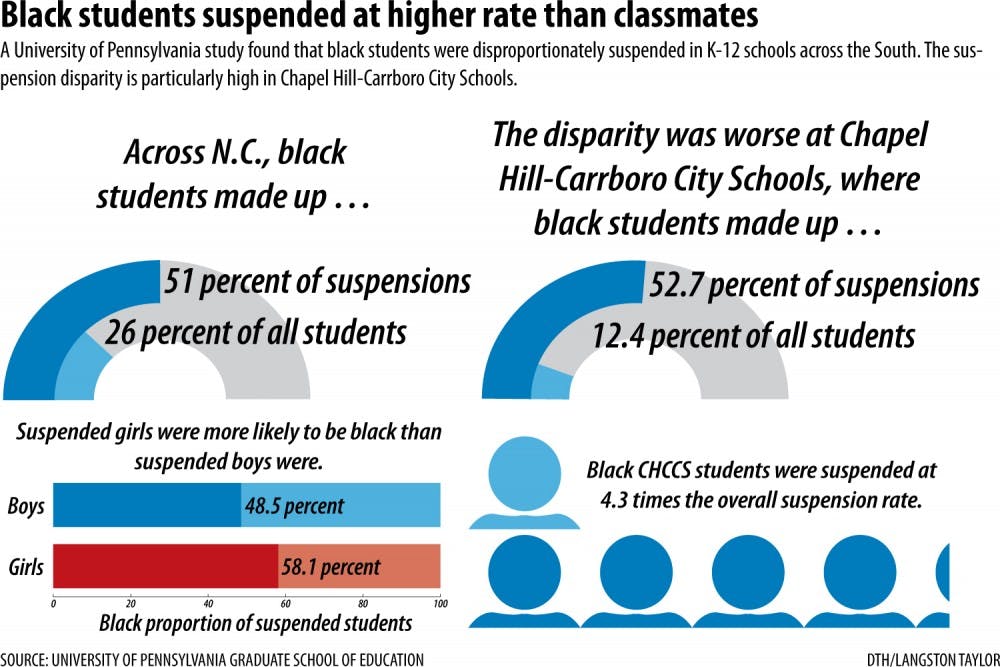

According to the report, black students comprised 26 percent of the student population, but 51 percent of suspensions and 38 percent of expulsions in North Carolina.

The report showed CHCCS fared worse than Durham, Wake and Orange County schools — while black students made up 12.4 percent of enrollment in the district, they accounted for 52.7 percent of suspensions.

“The district has taken it seriously,” said Jeff Nash, CHCCS spokesman. “We’ve taken our heads out of the sand, and we’re addressing this.”

One of the ways in which they have done so is by establishing a position dedicated solely to addressing the issue.

Sheldon Lanier joined CHCCS in October 2014 as the director of equity leadership, though Nash said some work had been going on in the area for years.

“I was surprised with the numbers,” Lanier said. “But this is school year (20)11-12 data. We have made significant gains in terms of suspensions as a whole but in particular with regard to marginalized students.”

Lanier said one way CHCCS has responded is by restructuring its student code of conduct. He said acts of violence are “nonnegotiable,” but things like defiance or disrespect might be more effectively handled in the classroom without a referral to the office.

“We are tasked to educate all students,” Lanier said. “We need them to be present to learn.”

Smith said such changes to the code of conduct haven’t been communicated to all students.

“I don’t get in trouble much,” she said. “But I don’t know anything about that.”

Lanier said CHCCS is continually working with teachers and administrators to combat implicit bias — deeply held stereotypes that unconsciously influence actions. He said teachers get training on how to combat such bias at least quarterly, though principals can implement training anytime they want.

Lanier said a big part of the problem is that when teachers earn their degrees, they only learn how to teach a narrow segment of the population: white males who are Protestant Christians, are middle class and have two heterosexual parents.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“There’s so much background stuff that goes into this,” he said, adding that even teachers who don’t fit this mold aren’t exempt from having implicit biases.

According to data provided by CHCCS, in the 2013-14 school year, black students represented 14.6 percent of enrollment but comprised nearly 46 percent of out-of-school suspensions. This is an improvement from the 2011-12 data, but blacks students are still disciplined at a rate more than three times their representation.

“This is work that’s never going to stop,” Lanier said, pausing reflectively before chuckling and looking up.

“And that’s why I’m here.”

state@dailytarheel.com