Still waiting

After moving past the initial shock of the report’s findings, the University community looked to the names in the report to determine who should be held accountable.

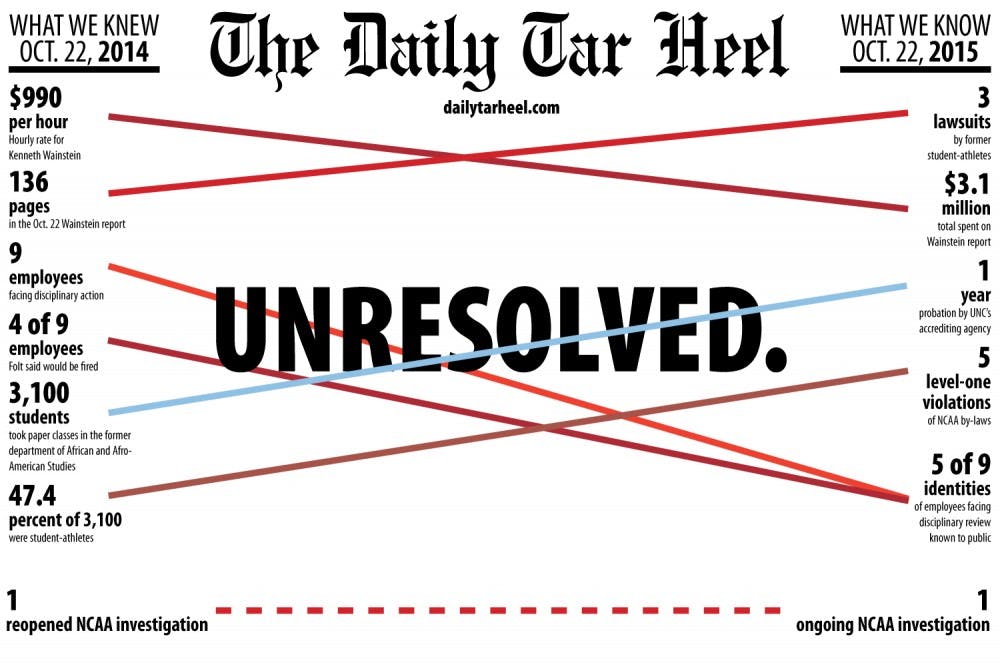

At the press conference last year, Folt said nine employees at the University would face disciplinary review — including four whose employment would be terminated.

That day, responding to questions from the crowd, Folt declined to share the identities of these individuals until they received their due process through the University’s human resources processes.

Two firings, of former athletic tutors Jaimie Lee and Beth Bridger, and two resignations, by former professors Jan Boxill and Timothy McMillan, are all that have been made public by the University after a settlement among UNC and 10 media organizations, including The Daily Tar Heel.

The Daily Tar Heel attempted to contact all current University employees who were specifically named in the Wainstein report, not including the “witness account summaries” section which summarized the more than 100 interviews the Wainstein team did. African, African American and diaspora studies professor Alphonse Mutima declined to comment on the report but did confirm that he is under review.

“The University hasn’t made a definitive decision regarding my situation,” he said.

Many other employees chose not to comment or could not comment due to the NCAA investigation.

Mutima, according to the report, pushed back against attempts by former administrative assistant and director of the paper class scheme Deborah Crowder to change grades and place students in his Swahili courses that Mutima said misbehaved. Despite his frustration, the report says Mutima ultimately took advantage of the paper classes by directing distracting students out of his classroom.

When asked about the time frame for the remaining employees assumedly still under review, Folt also declined to comment.

“As soon as we are completed with it, we will let you know. But it is only a tiny part of the amount of work we have been doing,” she said.

This protection of information is supported by several at the University, like Faculty Athletics Chairperson Joy Renner, who commended the school for not making to rash decisions.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“You’re wanting to know because you need to know or because you’re curious, or you can also look at it like if that were me, would I want the University to protect my rights?” Renner said.

“Do I need to know right now? I don’t need to know right now. Am I happy to know the University protects my rights? Yes, I am.”

A reformed UNC

Music professor James Moeser said the situation went undetected for so long because of two main fallacies: the fact that the academic support system for student athletes was, in reality, a part of the athletics department and the lack of review of the AFAM department and its chairperson.

The graduate school, which normally reviewed departments, didn’t have an AFAM master’s degree. Moeser, who served as UNC’s chancellor from 2000-08 during the height of the paper class scheme, said that fault was enormous.

“You could drive a truck through that loophole,” he said.

One of the silver linings for UNC was that the structural and cultural flaws mentioned by Moeser and expanded on by Wainstein were already in the process of being resolved.

UNC claims to have more than 70 reforms, with items ranging from the implementation of ConnectCarolina to small requirements like a dean’s signature on any grade change form.

“I do think that’s one of the positive benefits of going through something like this,” Folt said. “Really embracing what it means to truly reflect — how did we get here, and how do we really see ourselves proceeding in a way where we are proud and excited of what we are doing.”

One of the reforms UNC’s administration highlights is the formation of the Student-Athlete Academic Initiative Working Group, headed by Provost Jim Dean and Director of Athletics Bubba Cunningham.

“I don’t think you’ll find anything like that anywhere else in the country,” Dean said, citing the collaboration among the most senior academic and athletic administrators.

And while the reasons for the working group are unsavory, the results of its work have been positive in Dean’s eyes. He said the University “has never been so integrated.”

“I think what we did learn in the last two years is that we are delighted with where we are,” said Cunningham, referencing the entire University community and not a single reform in particular.

UNC law professor Michael Gerhardt — who helped in creating many of the University’s reforms in the last year on the Faculty Executive Committee — said constant self-criticism is needed to get ahead of past mistakes.

“We can’t be very sure that we’ve found the last misconduct that was committed,” Gerhardt said. “The very fact that we can’t be sure of it, I think, means we’ve got to be more vigilant.”

Gerhardt said the University should also focus on finding new potential gaps.

“How else can people try and abuse this system that we just haven’t seen in the past?”

Next dominoes to fall

In the spring, the University must reply to the NCAA’s Notice of Allegations, which cited the school for five level one violations — namely a lack of institutional control. A few months later, UNC’s yearlong probation implemented by its accrediting agency, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, will end, forcing the agency to make a ruling on the school’s status.

The worry of UNC being punished too harshly is certainly on the minds of fans of UNC’s sports team.

“I do not trust the NCAA to do this fairly,” said Moses Musilu, a sophomore and the public relations chairperson for Carolina Fever. “I understand their motive, but I feel like their main motive is to make an example out of us.”

Law professor Lissa Broome has been involved with the Faculty Athletics Committee and has served as the school’s representative to the NCAA and the ACC.

She believes the NCAA has mechanisms that allows for many different perspectives to be heard — like the fact the investigators do not rule on their findings — but in the end, UNC and its sports teams have to “trust that they are going to be fair.”

To keep accreditation, the University has to show it has corrected the broken accreditation standards revealed in the Wainstein report.

“What (SACS) focused on is of the things we said we were going to do in the future and said what’s the update — and we embraced as you do with anything from your accrediting agency,” Folt said.

“What do you learn when you decide to go inside-out, to put everything up for question? Here we are a multibillion-dollar operation, educating people, all these amazing things, and I think what I am probably proudest about is that it has become a place where nobody takes anything for granted.”

‘An ongoing tension’

Lloyd Kramer, a history professor who was a member of the Faculty Athletics Committee in the mid-2000s, said he is asked, and occasionally “razzed,” about the scandal at conferences and meet-and-greets with faculty from other schools.

But the people most fascinated with his take on the relationship between athletics and academics at institutions of higher education, he said, are his colleagues at European universities.

“They are always surprised by this particular aspect of American universities — why do you have these multimillion sports programs as a part of the university?” said Kramer, who specializes in European history and frequently travels abroad.

“It’s just an anomaly of our higher education system compared to other universities in the world.”

While Kramer is confident a scandal of similar scope and style could not happen again at UNC, he still notes a balance issue between the academic and athletic realms.

“There is an ongoing tension between the academic mission of the University and the pressure to win at the highest level in high-revenue sports.”

Former senior associate dean for social sciences Arne Kalleberg pinpoints Kramer’s feeling.

“The whole general ethos that sports has as a money-making factor with alumni and all that is a major issue,” said Kalleberg, who is currently a sociology professor.

To Renner, the Faculty Athletics Committee chairperson and radiology professor, changing this perception of athletics is on everyone — including the athletes.

“If all they talk about is their sport to people, then why wouldn’t anyone think that that person is here for something other than their sport?”

Kalleberg — the last dean to sign off on former AFAM department chairperson Julius Nyang’oro’s reappointment — did not say how he would remedy the issue but was firm on one thing.

“The larger problem of the culture of sports still exists.”

Check out this interactive graphic for more information.

university@dailytarheel.com