During her sophomore year of high school, a forensic pathologist came and spoke to her medical club. As he spoke, Janssen was intrigued.

“I looked around the room, and everyone else was completely grossed out,” Janssen said. She figured there must have been something unique about her and about the job that fit together.

'A different branch of medicine'

Betsy McDonald, the coordinator for several of UNC’s medical fellowships, said the profession has gotten a lot of free promotion in recent years from crime shows like “CSI.”

But right now, only one UNC fellow is accepted to the forensic pathology program each year. In 2017, the program will admit two students for the first time.

McDonald said Dr. Deborah Radisch, the program’s director and the state’s chief medical examiner, had to go to the state legislature to ask for more funding for another slot because of the need in the state.

But the nature of the work and the low salary in comparison to other medical specializations, Janssen said, can turn students away. In North Carolina, especially, medical examiners lack funding.

Typically, states and counties that are accredited by the National Association of Medical Examiners spend $3 per capita. North Carolina usually spends $1 per capita.

In the 2015 state budget, which was approved in September, state legislators allocated $800,000 over the next two years to help medical examiner's offices throughout the state with the transportation of bodies for forensic investigations. And they also increased the fee that medical examiners are paid for each autopsy from $100 to $200.

Though Janssen discovered forensic pathology in high school, not all students are exposed to it early on. She said the field needs more interest and more people.

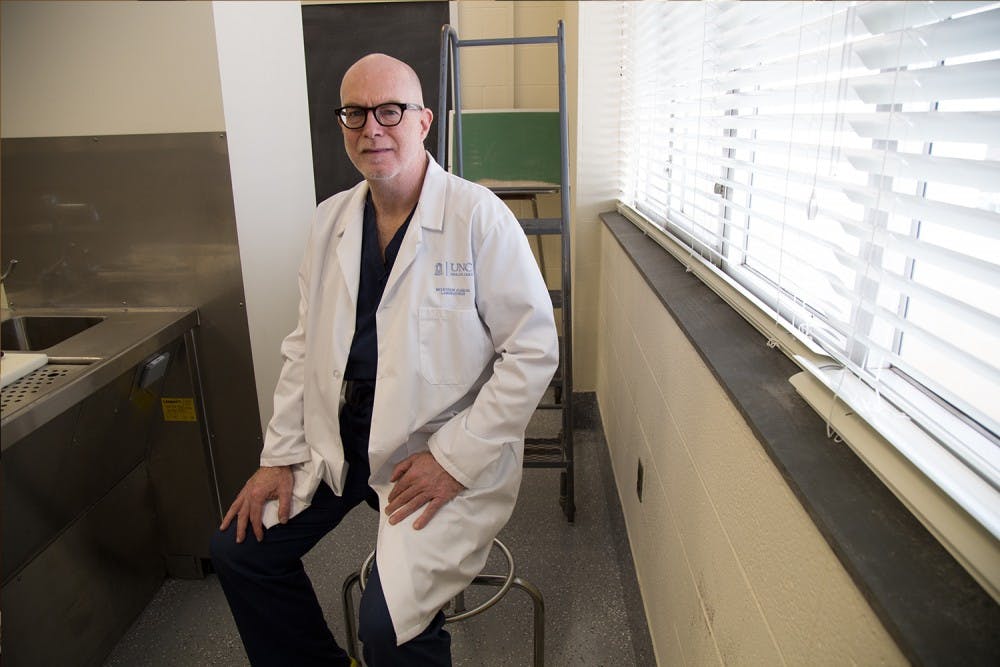

Dr. Craig Nelson, North Carolina’s associate chief medical examiner, said students who are interested in medicine often want to treat and work with living people, not dead ones.

“It’s very much a different branch of medicine,” Nelson said. “There’s generally a shortage of forensic pathologists nationwide.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

'Helping with some form of closure'

Although the majority of the work is investigation after death, there is, for some, a motive to help those that the deceased leave behind.

Vincent Moylan, an assistant professor at UNC’s medical school and Orange County’s sole medical examiner, lost four siblings before he turned 29.

Two of his brothers, he said, died under suspicious circumstances and he said he wasn’t pleased with how the police handled the investigation. Looking back, Moylan said the unsettling situation drove him toward forensic pathology.

He now views his work as a way to give a final answer to similar families who lose loved ones.

“Although it’s a small role, I’m actually helping with some form of closure,” Moylan said.

Moylan starts every conversation with family members the same way. “Really, all you can say is, 'You’re sorry,'” he said. “You can’t say, ‘I know how you feel.’”

Janssen said working with people on some of the worst days of their lives can be difficult, but they are usually grateful for any sort of answer that can be provided.

Thinking back to her medical club in high school, Janssen remembers asking each physician who came to talk to the students the same question: If you could go back in time, would you go into the same field?

“There must be something to it,” Janssen said she thought.

As she has delved into this work, she thinks she may have found that something.

When Janssen examines the body of a person who is younger than or the same age as her, she said it can be hard to separate her work from reality.

Facing human mortality on a daily basis, Janssen said, makes a difference in how she views her own life.

“Whenever I do anything, I think, ‘What if this is the last time I do it?’” she said. “It makes me appreciate what I have.”

She wonders if maybe that’s it — the reason the forensic pathologist back in high school was content with his career choice and why she’s found such meaning in her work so far.

“Maybe that’s why forensic pathologists are so happy: They’re made to appreciate life every day.”

@llizabell

special.projects@dailytarheel.com