Getting the call

Steve Farmer, vice provost for enrollment and undergraduate admissions, said it is important to understand there are several ways to measure enrollment statistics — numbers that are reported to the federal Department of Education, including those listed above, do not include students who may be mixed-race or biracial.

“Using this sort of frame, the class that we just enrolled in the fall of 2016, from the federal guidelines there were 125 black men in the class, but if you look at if anyone identified themselves as African-American at all, then there were 165 black men in the class,” Farmer said.

Farmer said by the end of this admissions season, he will have called or personally emailed all admitted black males — a new initiative introduced within the past few years. Other groups, including first-generation college students, also receive personal messages.

“It’s an effort to make sure that the wonderful people who have honored us by applying for admission don’t wander away from us without us showing them the best and truest face of the University,” Farmer said.

Aaron Epps, a junior and outreach chairperson for the Black Student Movement, said he received a phone call from Farmer when he was admitted.

“I remember getting a call, and getting really excited about it,” Epps said. “I thought it was great that they were calling me, that they really wanted me to come.”

Farmer said when the admissions office reads applications, they try to consider the whole student, rather than just race, ethnicity or any other single factor.

“There are situations over the course of the year where race or ethnicity could be a factor in admission,” Farmer said. “We do this because we believe pretty strongly that the University has a compelling interest in having a talented and diverse student body.”

Faison said a problem with black male enrollment is that the number of black males who enroll in college is relatively low.

“When you look at the national black male graduation rate from high school, it was only a little over 50 percent,” Faison said.

He said other factors, including the school-to-prison pipeline, the prison-industrial complex and rates of violence against black males could make enrollment lower, too.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“I’d also like to highlight Michael Brown,” Faison said. “He was on his way to college, and whatever school he was enrolling in, they lost another student because of that reason.”

A unique position

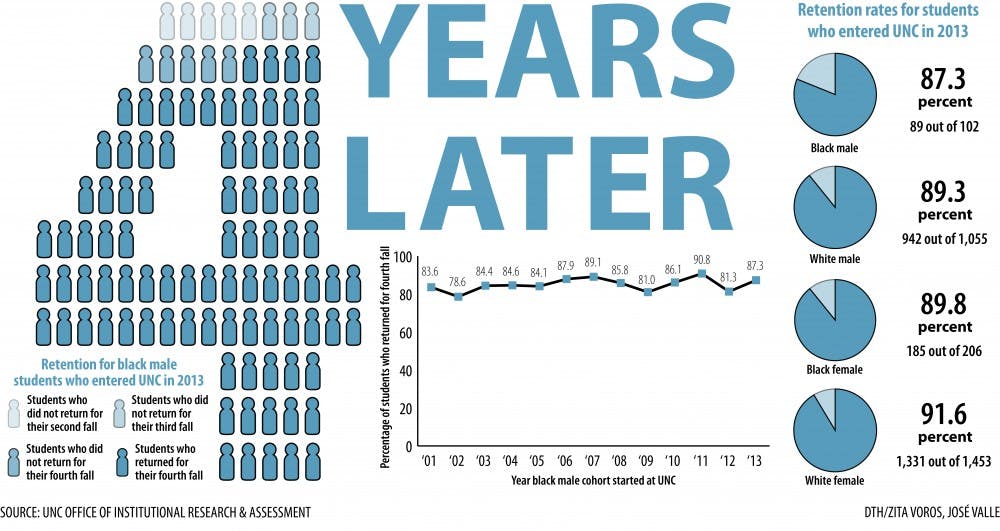

Farmer said he’s proud of the continuing efforts to increase enrollment for black male students, and is proud of how retention has increased in the past 10 years.

Faison said the fact that his position exists makes UNC unique.

“There are very few schools that have someone who works on this full-time,” Faison said.

Most of what Faison does in a day includes meeting with students, creating and running initiatives that create spaces for black male students and planning for the future.

“I’m most proud of the fact that we’re humble enough to know that we have work to do, and are willing to put resources toward finding solutions,” Faison said.

Forming a community

He said some of the problems he hears black male students mention most often are the assumptions other students make about them.

“... There’s an assumption that if you’re a black male student at Carolina you’re probably an athlete, and that’s not the case,” Faison said. “The question was what sport do you play, even when I was a student here.”

Deion Brown, a sophomore transfer student, said businesses in town are often surprised to hear him say he’s a student.

“If you go on Franklin Street or something, my debit card is the UNC version, and people are surprised that I go here,” Brown said. “I guess for me, it’s like, why would you think I don’t go here?”

Epps said he often doesn’t see himself represented on campus.

“I do feel like it’s easy to not see men who look like you in certain spaces, and to feel like you are the spokesperson for your entire group,” Epps said.

He said he’s been surprised by that, especially in his involvement in Honors Carolina.

“That is a space where really, it’s rare for me to find a male of color,” Epps said. “I would like to see a boost in those recruitment statistics around black men.”

Despite adversity, UNC’s graduation and retention rates for black males are high enough that other schools have taken notice.

“I’ve had calls from colleagues across the country to ask how they should be doing things,” Faison said.

Epps said Faison and his office have served as great resources for him.

“It has really served as a home for me, and many other men of color alike, and let them know that they are welcome and they are valued, and plugged them into different resources,” Epps said.

He said a main issue for him and people he knows continues to be the way the UNC administration talks about issues involving black males.

“When big issues will arise in the media, and obviously have an impact on students, there’ll be a very neutral letter,” Epps said. “I think letting men of color and students of color know that they are supported, and having that openly known would be helpful.”

university@dailytarheel.com