So Smith decided to move across the country to California, where she earned a master’s degree in history with a minor in Spanish from the University of California at Berkeley.

After moving back to North Carolina, she began teaching Spanish at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte.

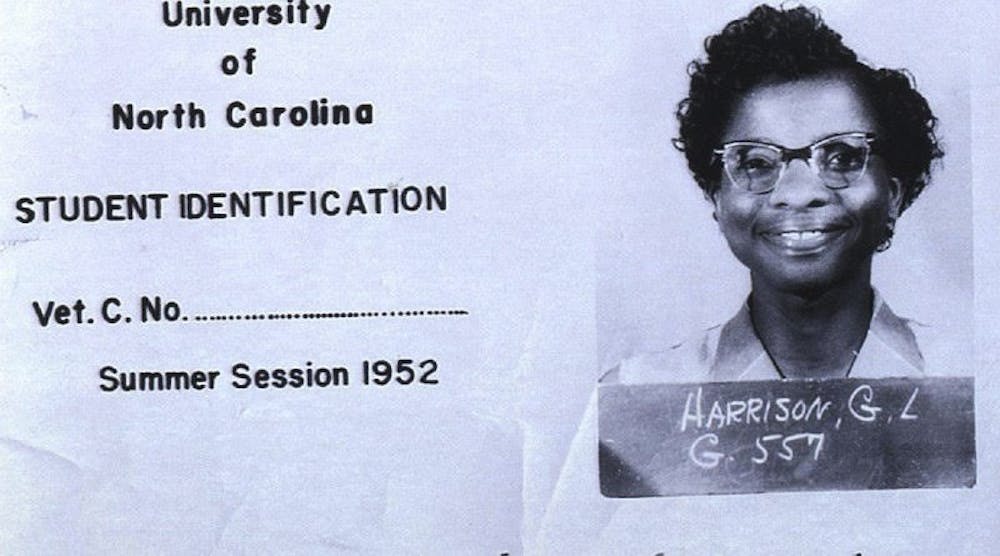

Despite accomplishing so much, Smith wasn’t done yet. In 1951, she decided to start pursuing her doctorate.

Smith was accepted to UNC, but once she arrived on campus, the University revoked her acceptance because of her race.

“She was told she couldn’t attend the school because she was a Negro,” Brown said.

With the help of the NAACP, Smith filed a lawsuit against the university. Before the court case was resolved, UNC reversed its decision and allowed her to take classes.

University archivist Nicholas Graham said one of the reasons that Smith is sometimes overlooked is that she was not the first black female graduate of UNC — she just attended summer sessions.

Brown said that, while at UNC, Smith struggled with segregationist policies.

“Mama didn’t really talk about it a lot,” she said.

In 1953, during her time as a professor at Johnson C. Smith, she married John Charles Smith.

“They were married 45 years,” Brown said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Smith was a woman of faith, heavily involved in her church, and her children say she was always optimistic and bright.

“She had a very witty, dry, corny sense of humor,” Dwight Smith, Smith’s son, said.

A life-long student, Smith kept her mind sharp following the end of her formal education.

“She would do word searches every day, she would read every day, even though the last couple of years she lived in a nursing home,” Brown said.

Smith was 91 when she died. Her intellect and tenacity helped pave the way for African-Americans seeking a college education at UNC.

university@dailytarheel.com