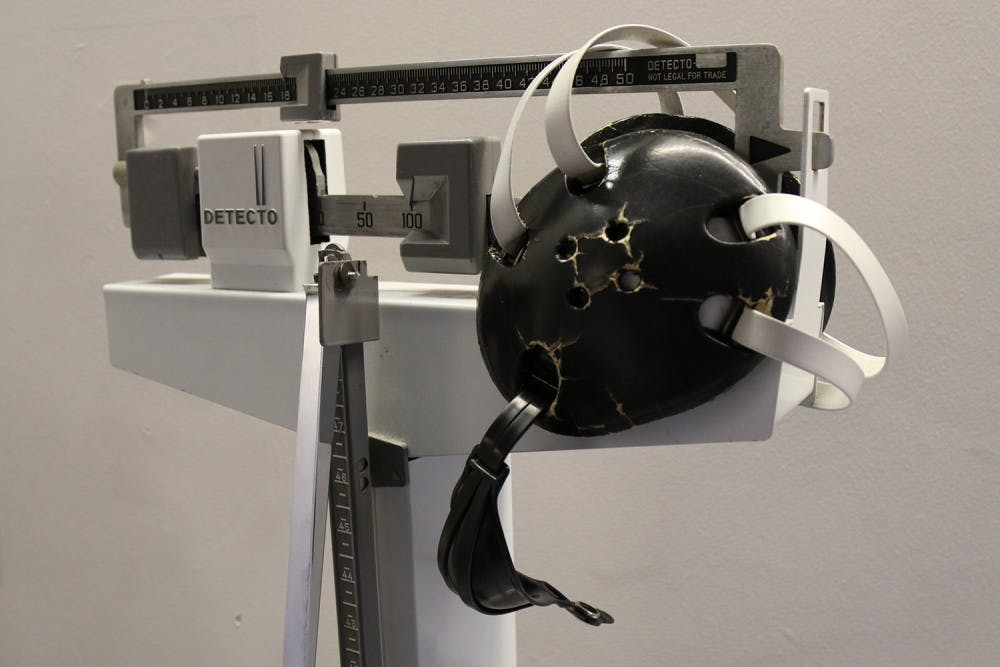

A wrestler at Michigan, Reese was wearing a sauna suit — shirt and pants made from trashbag material that expedite the process of sweating out water weight. He was completing a two-hour workout in a 92-degree room, trying to lose 12 pounds.

Reese was the third collegiate wrestler in a month to die from cutting weight.

Before Reese’s death, sports medicine experts and coaches conflicted. Coaches encouraged unsafe measures to have wrestlers compete at the lowest weight possible; a 1994 study found that in the 20 hours between the weigh-in and the match, wrestlers gained 7.3 pounds on average (mostly in water weight).

Brian Hendrickson, the executive editor of NCAA Champion Magazine who wrote the story “Wrestling Away From a Troubled Past,” said coaches were attached to unsafe weight cutting practices because they believed the measures gave a competitive advantage. Mistrusting sports scientists, they refused to heed warnings of the dangers of sauna suits.

“What was really kind of behind the scenes was this war going on,” Hendrickson said.

After the three wrestlers died, coaches complied with reform because the future of the sport was in jeopardy.

The NCAA raised weight classes, moved weigh-ins to one hour before the match and banned sauna suits. Weight certifications testing hydration, body fat percentage and other variables set a minimum weight that players cannot fall below during the season.

One of the biggest changes is in attitude within the sport. Hendrickson saw this manifest in the responses to his story.

“What I was surprised by was how much they embraced having the story out there and were glad to have the conversation…” he said. “I think they felt like they could show how much they changed.”

***

Though regulations paved the way for improvements, problems persist. J saw wrestlers use sauna suits in high school. UNC wrestler Troy Heilmann said he can tell when a wrestler is cutting weight unsafely.

“They have a — what you say in the wrestling world — sucked out,” Heilmann said. “They look skinny. You can see their cheekbones and stuff like that.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Research studies have found high school wrestlers are more likely to have an eating disorder or engage in disordered eating than other men of similar ages. Bardone-Cone said some wrestlers will restrict and then binge eat in the offseason.

“They’re very irritable, you know, when they’re in this kind of — restricting their food and trying to lose weight,” Bardone-Cone said. “And we see that with anorexia.”

Athletes as a whole are more likely to develop eating disorders, but this risk rises for sports that emphasize slimness in conjunction with success, like running, gymnastics and wrestling.

While most eating disorder research focuses on women and girls, a 2004 study published in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine found that eight percent of male athletes exhibited the symptoms of an eating disorder, compared with 0.5 percent of male non-athletes.

“Males are not immune,” Bardone-Cone said. “And this is a thing that happens, and it causes them physiologically and psychologically the same kind of problems.”

***

When Heilmann lost the 141-pound spot his sophomore year at UNC, he had to drop to a lower weight class — 133 pounds — if he wanted to start.

“I went down for the team, basically,” Heilmann said.

Head coach Coleman Scott walked him through the process to make sure he was safe. Scott took Heilmann grocery shopping to show him healthy foods and recipes and consulted a dietician who works with MMA fighters. Heilmann, who struggled with weight in high school because of a lack of knowledge and resources, said he learned how to balance making weight and being healthy through Scott.

“As a wrestling coach, I’m not here to make a kid cut a bunch of weight or get him to do something that he physically can’t do …” Scott said. “I’m here to promote a healthy lifestyle and make sure that the kids are doing the right thing and educate them about their body.”

The team meets with UNC nutritionists at the start of the season. Scott meets with them regularly, too, along with researching online and talking with outside nutritionists to hone his knowledge.

The frequent meetings with Scott have made it easier for UNC sports dietician Rachel Stratton to work toward a safer competing environment for UNC wrestlers than there was in the past.

“I only have positive things to say about Coach Scott,” Stratton said. “He is an advocate for long-term health and an advocate for safe nutrition practices, so I’d say that our values of nutrition align.”

***

For wrestlers who are struggling, Bardone-Cone ponders one question: Then what?

Bardone-Cone is concerned with life after wrestling for those who engage in disordered eating. While some wrestlers, like J, can transition back to a normal diet, she said others might struggle to quit the issues that stem from unsafe weight cutting.

“As researchers, we want to know who takes which path,” Bardone-Cone said, “so we can help figure out who do we need to intervene with to make sure that someone who’s probably going to keep with those behaviors doesn’t.”

Heilmann has seen improvement in the sport firsthand. He’s noticed an emphasis on education and healthy weight loss; his younger brother, a high school wrestler in New Jersey, has benefitted from access to a nutritionist and information about how to safely manage weight.

“My brother does it the right way …” Heilmann said. “I’ve heard a lot of other kids are doing the same thing…”

“I think that the problem’s becoming fixed because people are learning more about it.”

@rblakerich_

sports@dailytarheel.com