Matt Gross, policy director at NC Child, said opponents to the state’s current juvenile court jurisdiction have tried to pass a Raise the Age bill for more than a decade.

But things are different this year, he said.

A committee created by N.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Martin to focus on amending North Carolina’s court system recommended that the state consider 16- and 17-year-olds as juveniles, excluding those who commit violent felonies.

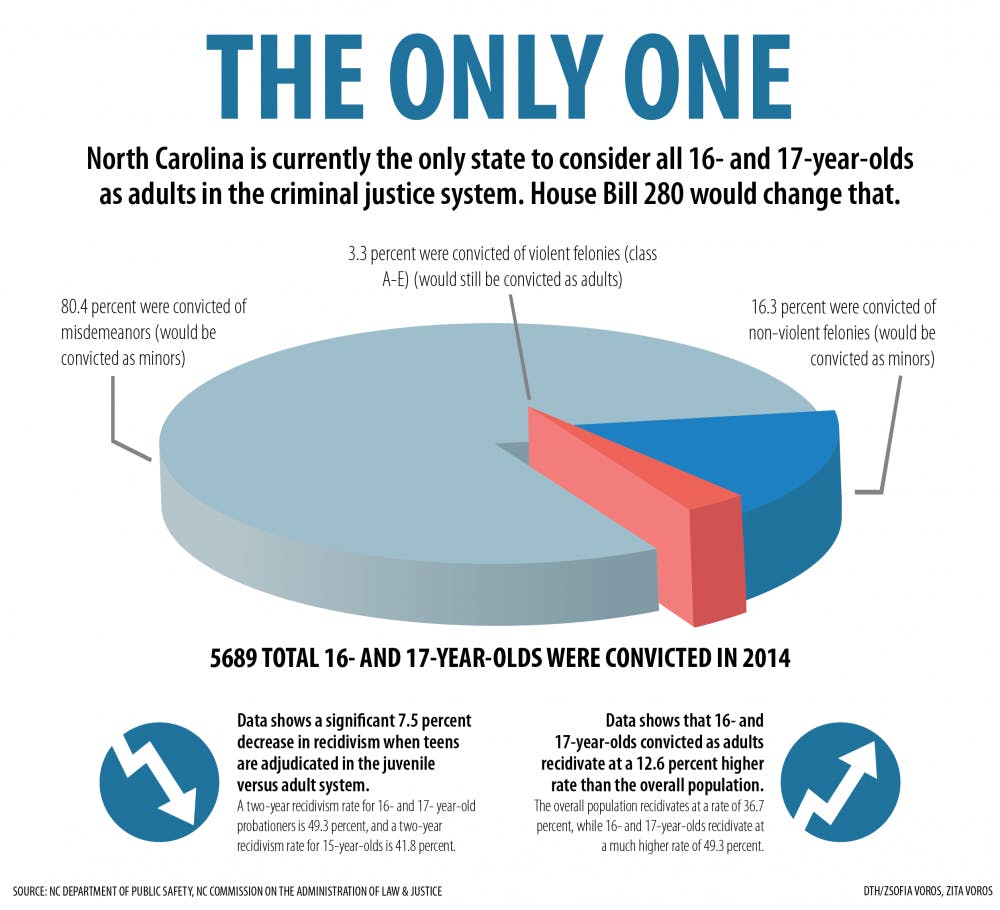

According to the committee’s report, of the 5,689 16- and 17-year-olds convicted in 2014, only 3.3 percent were convicted of violent felonies. The majority of these convictions in 2014 — 80.4 percent — were misdemeanors.

The committee’s collaboration paved the way for bipartisan support, Gross said.

“They’ve all come together and said ‘This is what we agree on, this is what needs to be done’ and it’s carrying a lot of weight,” Gross said.

House Bill 280 is currently sponsored by 68 House Representatives — over half of the 120 members of the state House of Representatives.

The support of the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association is especially significant, Gross said.

Eddie Caldwell, executive vice president and general counsel of the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association, said the association supports the bill contingent on the allotment of adequate funding.

He said there are various problems in the juvenile justice system that must be fixed before two age groups are added to the system.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“This report from the Chief Justice’s commission that is now in this bill fixes those problems and addresses those concerns,” Caldwell said.

Costs and pushback

The committee’s report estimated the state will see economic benefits if the age of juvenile court jurisdiction is raised.

Raising the age could result in a net benefit to the state of $52.3 million, according to a finding in the 2011 Youth Accountability Planning Task Force report.

The report said reduced recidivism would account for a large portion of the savings.

Tarrah Callahan, executive director of Conservatives for Criminal Justice Reform, said this economic net benefit is called the Raise the Age effect. In states that have passed similar laws, the number of juvenile offenses drop dramatically over a period of years, she said.

The upfront cost of the bill tends to be the primary concern of those opposed, Callahan said.

Up until year four of implementation, Gross said costs associated with the bill would likely rise from an estimated $16 million in year one to an estimated $50 million to $60 million in year three. But year four is when cost savings start to accrue, he said.

“Once you’ve gotten through this initial upfront investment you start to see cost savings because you’re having fewer of these children go on to have to be in and out of the criminal justice system as they’re adults,” Gross said.

Peg Dorer, director of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys, said the bill will create costs in part due to the increased amount of services required to rehabilitate a juvenile offender.

“There’s a broader range of services that are given to someone who offends as a juvenile because the hope is that they can rehabilitate them,” she said.

But Nicholson said the short-term investment will drive long-term savings.

“All of the research shows that by treating these children as juveniles in the juvenile system they will be less likely to reoffend and thus less likely to end up in this cycle of court involvement and incarceration that is costly to taxpayers,” she said.

‘An investment in our children’

When teenagers are adjudicated in the juvenile system as opposed to the adult one, there is a 7.5 percent decrease in recidivism, the committee’s report said.

Callahan said it is important for kids to be in the juvenile system for low-level crimes in order to break the cycle of repeated crime.

“It truly is an investment in our children,” she said. “These kids end up getting victimized at an overwhelming rate in the adult system.”

Youth offenders have a higher probability of being victimized by physical violence in adult prison than older offenders, according to the report.

Callahan said, under the current law, if a child in South Carolina and one in North Carolina commit the same crime, only the child in South Carolina could exclude it from his record when he applies to UNC.

“The reality is, there is a net economic benefit, but beyond that, we’re putting our children at such a disadvantage by proceeding the way that we are,” Callahan said. “They’re at a disadvantage to the other 49 states.”

@crmetzler

state@dailytarheel.com