The common Confederate soldier

The first factor distinguishing Silent Sam from other monuments and buildings is what it symbolizes: the common Confederate soldier.

Fitzhugh Brundage, a UNC history professor with a focus in America since the Civil War, said the common Confederate soldier, and its anonymous nature, represents white, Southern male valor.

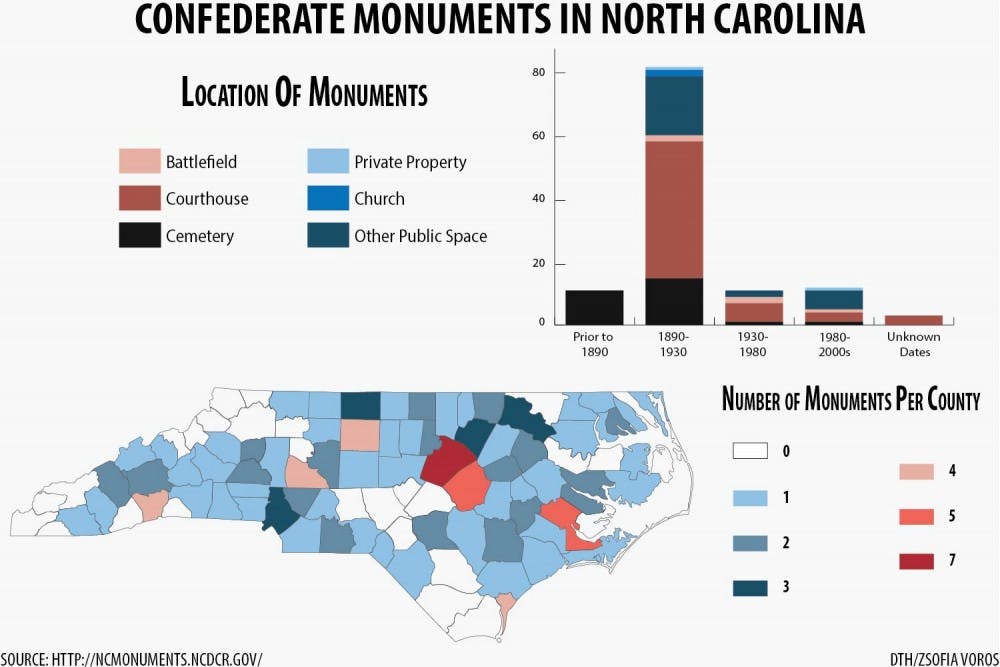

Brundage said this was a common theme among Confederate monuments erected between 1890 and 1930. In total, 52 of the 83 Civil War monuments erected during this period depict a common soldier, according to the North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources monuments database.

“These monuments were different in character because they were monuments to the common Confederate soldier, rather than symbols of funereal traditions,” he said.

‘Explosion of monument building’

Another force propelling the outcry against Silent Sam is the time period in which it was erected — almost 50 years after the end of the Civil War.

Silent Sam was part of a second wave of monuments erected in the South, Brundage said.

It was built in 1913 using funds raised by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, one of the most prominent groups that funded Confederate monuments at the time.

While Francis Venable, UNC president from 1900 to 1913, said the University itself would not pay for the memorial, he was actively involved in raising money by sending letters to alumni, according to University archives. In 1914, the University paid $500 owed on the monument when other fundraising efforts came up short.

“From 1890 to 1930 there was just an explosion of monument building, and those monuments were different in character, different in location and different in terms of who was responsible for erecting them,” Brundage said.

According to North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 72 out of North Carolina’s 100 counties have at least one Confederate monument. Prior to 1890, 11 monuments related to the Civil War were erected in North Carolina.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

In the period from 1890 to 1930, however, 83 total monuments were erected across the state.

Harry Watson, a UNC history professor, said this wave of monument building was largely during the time the South used provisions like poll taxes and literacy taxes, as well as intimidation and violence, to severely limit the political power of blacks in the South.

“[Silent Sam] came up during a time when blacks were getting rights,” Brown said. “And there’s a clear purpose in erecting a statue to white supremacy when blacks are getting rights.”

‘He’s always going to be the bullseye.’

Brundage said Silent Sam’s prominent location also lends to the controversy.

“It’s not just a monument on UNC’s campus; it’s a monument on one of the most familiar civic spaces in the state,” Brundage said. “He’s always going to be the bullseye.”

McCorkle Place is one of the prettiest places on campus, Brundage said, and acts as a front door or living room for the rest of campus.

“That’s what I would say about any of these monuments that are located in very privileged, conspicuous civic space,” he said. “Ask yourself, ‘How does this monument, whether it be a Confederate monument or not, communicate what it is that I think is important about my community?’”

But the public placement of Silent Sam is not unique. Of the 83 monuments erected between 1890 and 1930, 63 were located on public spaces.

For Brown, this placement communications a distinct message to its students.

“The University stands for hatred, and that’s really clear when a symbol of white supremacy and hatred for people of color is at the center of our campus," she said. "And not just on our campus, but it’s at the very head of our campus."

Layers of meaning

In contrast to statues honoring common Confederate soldiers, some state monuments — like the one in Asheville honoring Zebulon Vance, North Carolina’s governor during the Civil War — are meant to memorialize someone’s entire life’s work.

Brown said even though the removal of Silent Sam is activists’ priority, there will likely be action taken toward building name changes in 16 years, once the 16-year freeze placed on name changes to University buildings by the Board of Trustees expires.

Cecelia Moore, a historian and project manager of the Chancellor’s task force on UNC-Chapel Hill history, said the purpose of the 16-year freeze was to try to give time for students to form a broader understanding of the University’s full history.

“I mean, one of the things in the last few weeks is that there has been a really lively debate on social media, in person and everywhere, and that actually means more people are learning more about it,” Moore said. “I, of course, would love to see that happen more.”

Changing the names of campus buildings named after slaveholders, segregationists or people who would be considered racist by today’s standards would change a large proportion of the building names on campus, Watson said.

Watson said the University was founded by imperfect people who were obnoxious on the subject of race, which is something everyone has to come to terms with.

“And yet, we wouldn’t have a University, and we wouldn’t have many of the things that we’re glad to have in North Carolina without those people,” he said.

enterprise@dailytarheel.com