Not proud but also not in violation

The COI did not conclude that the University lacked institutional control.

“While the university admitted the courses failed to meet its own expectations and standards, the University maintained that the courses did not violate its policies at the time,” the NCAA said in a press release.

UNC Chancellor Carol Folt said she was not surprised by the case’s resolution, though she said Friday was not a day of celebration.

“I appreciate the real scrutiny that the NCAA put forward, but I think this is what I expected to be the real outcome,” Folt said.

Bubba Cunningham, UNC athletic director, said the University’s conduct did not violate any bylaw.

“Unfortunately, sometimes the behavior that you’re not proud of just doesn’t quite fit into a bylaw or rule or something, and that’s what we’ve been talking about for five years,” Cunningham said in a press call in the company of Folt. “We’re not proud of the behavior, but we didn’t think it violated a bylaw.”

Panel was "troubled"

Still, Sankey said the panel was “troubled by North Carolina’s shifting positions about the report,” referring to the University’s response to the Cadwalader report, conducted by attorney Kenneth Wainstein in October of 2014.

The panel said UNC initially accepted its accreditor’s description of its courses as “academic fraud.”

“Despite these early admissions, UNC pivoted dramatically from its position roughly three years later within the infractions process,” the panel’s decision said.

But Cunningham said the University did not waver from its commitment to the facts, and that those facts were simply woven into a narrative with which UNC did not agree.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

On the day the Wainstein report was publicly released in 2014, Folt acknowledged the academic fraud within the African and Afro-American studies department was multifaceted.

"It is just very clear that it was an academic issue with the way the courses were administered, and it is clearly an athletics issue," Folt said.

Mary Willingham, a former learning specialist who studied student athletes’ literacy rates, said she continues to be surprised by University attempts to distance itself from the Cadwalader report.

“It’s fascinating, isn’t it, that now Chancellor Folt is saying those classes were fine,” Willingham, who was the “whistleblower” in the scandal, said. “Those classes weren’t fine.”

Student athletes weren’t the only ones

To constitute an ‘extra benefits violation,’ Sankey said UNC’s courses in question would have also needed to be exclusively available to student athletes.

“While student-athletes likely benefited from the courses, so did the general student body,” the panel said in its decision. “Additionally, the record did not establish that the University created and offered the courses as part of a systemic effort to benefit only student-athletes.

Jonathan Weiler, a UNC professor of Global Studies, said this aspect of the COI’s decision seems like it could reward athletic programs that blatantly cheat.

“If I’m an athletic department, and I want to make it easier for my athletes to maintain eligibility, and I create a parallel curriculum — what the NCAA is saying, that as long as there are some non-athletes in that curriculum, I can do that,” Weiler said.

Folt responded to a question asking about whether this will motivate such behavior in other programs.

“I don’t think there’s a President or a Chancellor in the country who would like to go through this,” Folt said.

The NCAA and the enforcement and infractions processes are under constant review, Sankey said. But UNC’s case does not signal a need for drastic changes in the NCAA's academic policies.

“This isn’t a triggering event, and I think the University has spent a great deal of time reviewing itself,” he said.

“We’re not the regulatory body for academics anymore”

Willingham, who compared the NCAA to a cartel exploiting black men’s bodies for sport, said the COI’s decision sends a message.

“It looks like the NCAA body has just told us, ‘hey, we’re not the regulatory body for academics anymore,’” she said.

The panel’s decision said it would call on NCAA President Mark Emmert to forward its findings to the accrediting body of a member university in question — in UNC’s case, to the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges.

Belle Wheelan, president of SACS, said forwarding information between organizations is a formality that is frequently observed in order to evaluate whether their decisions impact one another.

“There is nothing in the NCAA standard that puts (the NCAA) out of compliance with what we did because they didn’t do anything,” she said.

SACS already made a determination on UNC’s ‘paper courses’ and any allegations of institutional misconduct. As issues were restricted to a single academic program, Wheelan said the SACS body did not discredit the University — but that was a conversation that occurred.

“They gave them the most severe sanctions that we could give an institution to send a very powerful message that this is ridiculous,” Wheelan said.

She said the NCAA seems to apply a different definition of academic fraud, or that UNC defended it differently.

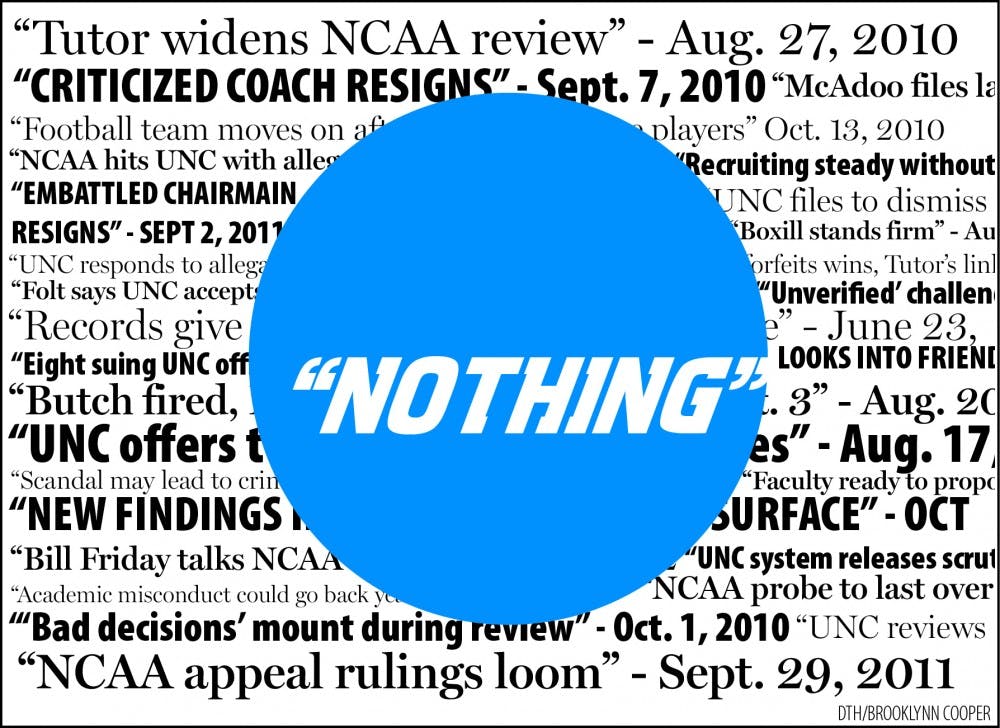

The aftermath of UNC's academic scandal

Weiler said the NCAA’s Friday decision cannot erase years of comments shrouded with judgment on ‘paper classes’ at UNC.

“That’s a painful part of just having been through all of this, and the (NCAA) report today doesn’t say that that wasn’t happening — it just says that we can’t do anything about it,” he said on Friday.

Currently, college athletes are not paid under the assumption that they are receiving something greater in their academic opportunities, Weiler said.

“I think the interesting question now is when they continue to be on the other side of litigation about paying athletes,” he said about the NCAA’s distancing of itself from academics.

Wheelan wondered about the term student athlete in relation to the NCAA’s decision.

“They are student athletes,” she said. "I’m at kind of a loss how they separate the two — but apparently they can.”

university@dailytarheel.com