I wrote my pro-Oxford comma viewpoint immediately after it was decided Emily and I would go head to head on the issue in today’s editorial. It was a short, witty piece in which I told the story of my day through a series of sentences that, through their lack of an Oxford comma, had ambiguous meanings. I was so proud of it! I used all the classic examples, and even ended on a sentence that implied Emily and our editor-in-chief Tyler Fleming were escaped convicts — in hindsight, my examples got progressively more extreme and bizarre as the article went on. But, alas, my masterpiece will never see the light of day.

Because yesterday I received a shot across the bow: a sneak preview of Emily’s anti-Oxford comma viewpoint. And it was good. Too good, in fact, for me to present my case in such a lighthearted fashion. So, armed with a knowledge of Emily’s arguments and the religious fervor only discussions of Cary Grant, tennis, and punctuation can inspire in me, I set out to formulate a defense of the Oxford comma so persuasive that it would win over even an anti-Oxford Commatarian like Emily.

A great deal of my writing process focuses on style. I’ll spend almost as long considering my word choice, syntax, and, yes, punctuation as I do the actual idea behind the article. I am as concerned with creating pieces that are enjoyable to read as I am in creating pieces that are well argued. One of my writing heroes, William F. Buckley Jr., was famous, or perhaps infamous, for his use of obscure and esoteric language, and was once asked by a fan why he used the word “irenic” in place of the synonymous and better-known "peaceful." Buckley coyly replied, “I desired that extra syllable.” Buckley believed, properly, I would argue, that good writing requires more than technical soundness. It requires an understanding of what is pleasant to the ear and how to keep the reader engaged with the text.

Let me provide an example. While it is possible to write five grammatically and technically correct short sentences in a row you will rarely see it occur, because it would create a staccato rhythm that would sound awful. The written word must be seen with the eyes to be comprehended, but it is not a visual art. We write for the ear, and certain structures and ordering simply sound better. Short sentences must be broken up by a long sentence in order to avoid monotony and vice versa.

Another example. There is a reason why in the second sentence of the preceding paragraph I placed “five” ahead of “grammatically and technically correct” and “short.” The phrases all describe “sentences,” yet placing “five” last in the order or “short” first would result in some rather clumsy prose. We are not taught how to order adjectives, yet all English speakers implicitly understand how to do so and find sentences that fail to do so unnatural.

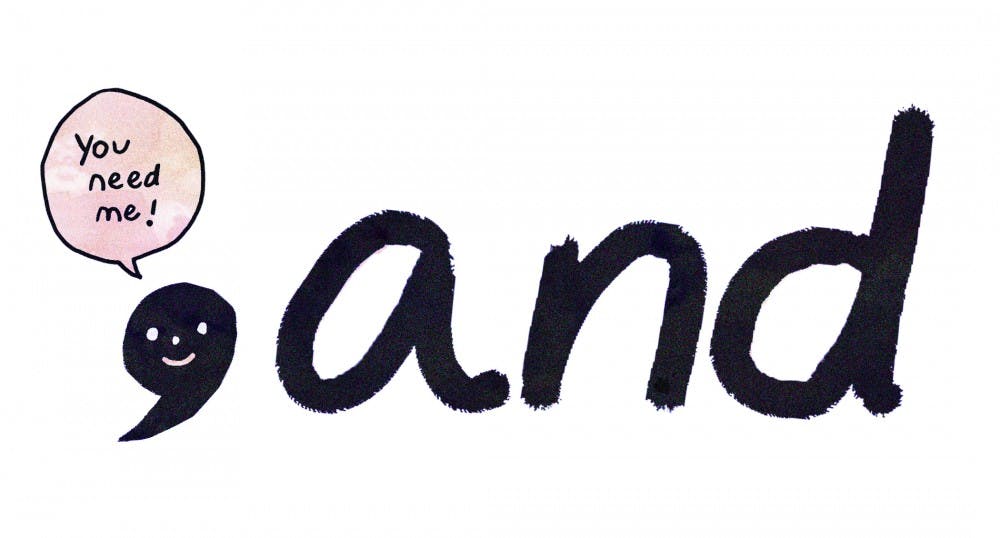

And now, already six paragraphs into my article — talk about a buried lede — I’ll explain how this ties in to Oxford commas. The typical pro-Oxford comma argument is that it prevents potential ambiguities, that it provides a nice consistency in writing, whereas removing it complicates the process.

Emily countered this quite nicely, by pointing out that such ambiguities can often, though not always, be avoided anyway by reordering lists. But, what about when doing so creates an awkward sentence? Using the Oxford comma allows you to order the list however you please. You don’t have to worry about avoiding double meanings because that’s already covered, giving you creative breathing room to consider the order that is most appealing. Removing that final comma can force you to twist sentences into odd shapes to avoid confusion.

One popular example of why we need the Oxford comma is the sentence, “We invited the strippers, JFK, and Stalin.” Without the Oxford comma it is unclear whether JFK and Stalin were invited in addition to the strippers or are the strippers themselves. There are three ways to re-order this sentence in order to avoid uncertainty while still refraining from using the Oxford comma: “We invited JFK, Stalin and the strippers,” “We invited Stalin, the strippers and JFK,” and “We invited JFK, the strippers and Stalin.” Each option is technically sound, yet each proves awkward in some manner. It seems odd to separate the two named individuals, placing “the strippers” between “JFK” and “Stalin.” And starting with two named, specific individuals and moving to an unnamed, more general group seems odd as well. There may be no rule on the matter, but moving from general to more specific produces the most appealing list.

Emily noted the JFK/Stalin/strippers example in the opposing viewpoint, giving two more ways it could be re-written without the Oxford comma and still make sense: either by identifying all the parties by their names — “We invited Tyler, Rachel, JFK and Stalin” — or professions — “We invited the strippers and the deceased world leaders.” Such edits are, again, technically sound, yet still result in some confusion and fail to grab the reader’s attention in the manner the original sentence does. Who are Tyler and Rachel? Which deceased world leaders?