CORRECTION: A previous version of the graphic that ran with this story misrepresented the average wages paid to UNC faculty. The graphic has been updated.

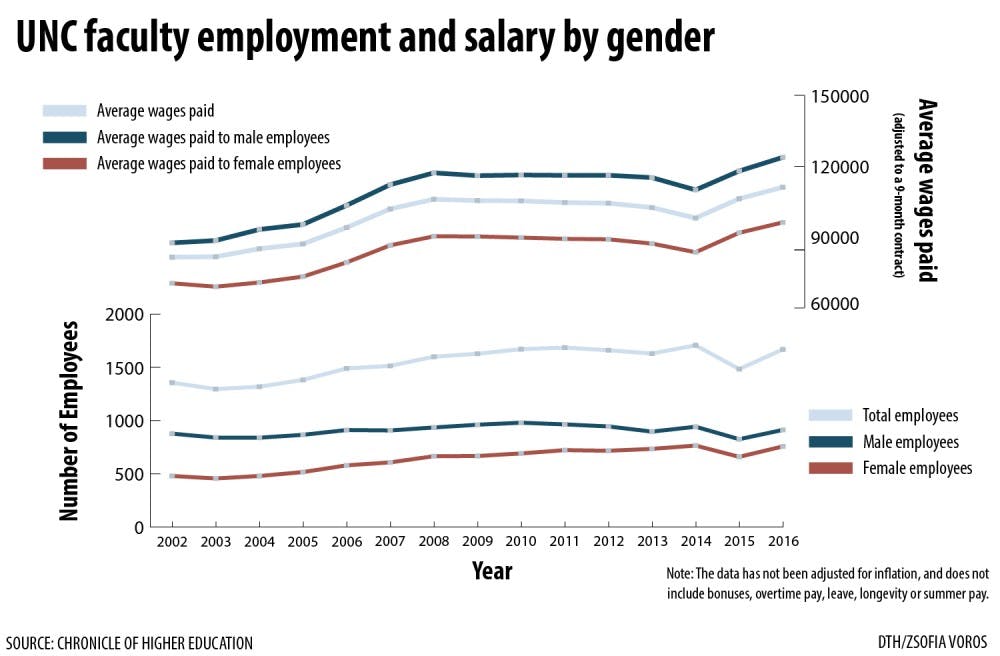

Female professors at UNC on average made $0.85 per dollar paid to their male counterparts in 2016, according to provisionary data archived by the Chronicle of Higher Education.

The highest echelon of academic rank is the position of full professor. At UNC, the average salary for male full professors was $158,715 in 2016, the most recent year for which full data is available. Meanwhile, the average salary for female full professors, who are outnumbered over 2:1 by male full professors, was $138,429.

In each of the six categories of academic rank, male professors outearned their female counterparts. The Chronicle data, which spans nearly two decades, shows the same wage gap existing without exception as far back as 2002.

“When providing analysis of salaries, it’s important to note that data sets which group everyone into one category fail to take into consideration important factors such as whether a faculty member is tenure track or fixed, the area of academic discipline or years in rank, all of which greatly affect faculty salaries and ranges,” said Assistant Provost for Academic Personnel Ann Lemmon in a statement.

Full-time faculty salary data gathered by the Chronicle is obtained through the U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). The Chronicle has used IPEDS data to report salary averages for male and female professors, organized by academic rank, at almost 5,000 colleges.

The disparity among UNC professors may appear to be discrimination at first glance, but UNC professors say other factors may be at play.

“You can’t offer two candidates different amounts of money for doing the same job if they’re completely identical. Legally, you can’t,” said Kalina Staub, UNC teaching assistant professor of economics. “Usually there’s some sort of salary range for a position, and a lot of your wage offer is determined by things like your education, your experience, things that influence your ability to perform the job.”

Staub said the right for females to be educated at the highest level is still a relatively new development, which she suggests may influence the amount of wages offered to a female professor compared to a male professor.