For professors, student evaluations are used to assist decisions on promotions, raises and tenure. But research from North Carolina State University shows that the evaluations a professor receives are linked to their gender, with male professors receiving higher and more favorable ratings than female professors.

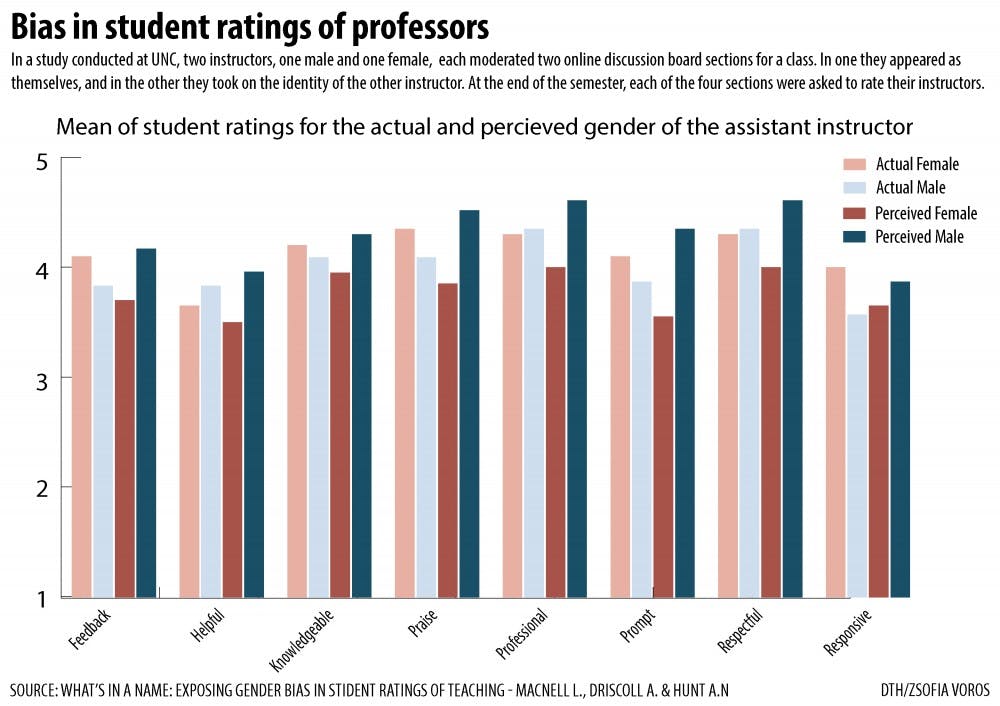

In 2014, researchers at N.C. State used online courses, where an instructor’s gender could be hidden, to test this gender bias. Four sections of an online class were taught by two instructors: a female instructor and a male instructor. Each taught two sections, using their true identity for one and adopting a name of the opposite gender for the other.

At the end of the course, students were asked to rate their professors on fifteen positive qualities, ranging from knowledgeable and fair to caring and helpful. In every category except one, the scores the male professor received dropped when he adopted a female name. Meanwhile, the female professor received higher scores in every category when using a male name.

“I have a colleague who is about is the same age as I am, who has been at UNC about the same time that I have. We used to both teach (POLI) 150 pretty regularly, and we have the same grade distribution. He’s a good teacher, and I think I’m a reasonable teacher as well, but I would always get much harsher evaluations,” said Layna Mosley, a UNC professor of political science. “There is a set of societal expectations for how faculty behave, so the same sort of behavior for a female versus a male professor is interpreted differently.”

At University of California-Berkeley, Texas Tech University and Saint Mary’s University, several other studies have supported N.C. State’s findings that student-teacher evaluations are biased against female professors.

“Part of what’s going on is that students expect female professors to be nurturing and compassionate towards students. They do not expect the same of male professors,” said UNC professor emerita of sociology Sherryl Kleinman. “If a male professor acts compassionately toward students, that gets him extra points. A female professor who is compassionate as well as competent is likely to be seen as average.”

Mosley also emphasized the idea that traditional biases play a role in how female professors are evaluated, using her experience in comparison with her male colleague.

“Maybe it’s just that he’s more affable, but I think that it’s also probably about that there are expectations, you know, if he takes a hard line on something, that’s seen as different or perhaps more acceptable and expected than if a women does the same,” Mosley said. “I think women are under more pressure to conform to societal expectations, and women who fail to do that are judged a little more harshly.”

In the UNC System, student evaluations are a required component in faculty performance assessments. The majority of departments use a standard survey which asks students to rank professors on characteristics such as communication, fairness and feedback. Students are asked to provide a free-response answer assessing the instructor overall. At UNC, 11 of the 14 professional schools also use Carolina Course Evaluations, which allows for the creation of customizable evaluations.