“Students are scrambling because there’s a scarcity of resources, and to go to college costs more than ever before,” Hernandez said.

Sara Goldrick-Rab and the Wisconsin HOPE Lab conducted one of the first studies on this issue in 2015 and found that around half of community college students at the time of the study were struggling with food or housing insecurity.

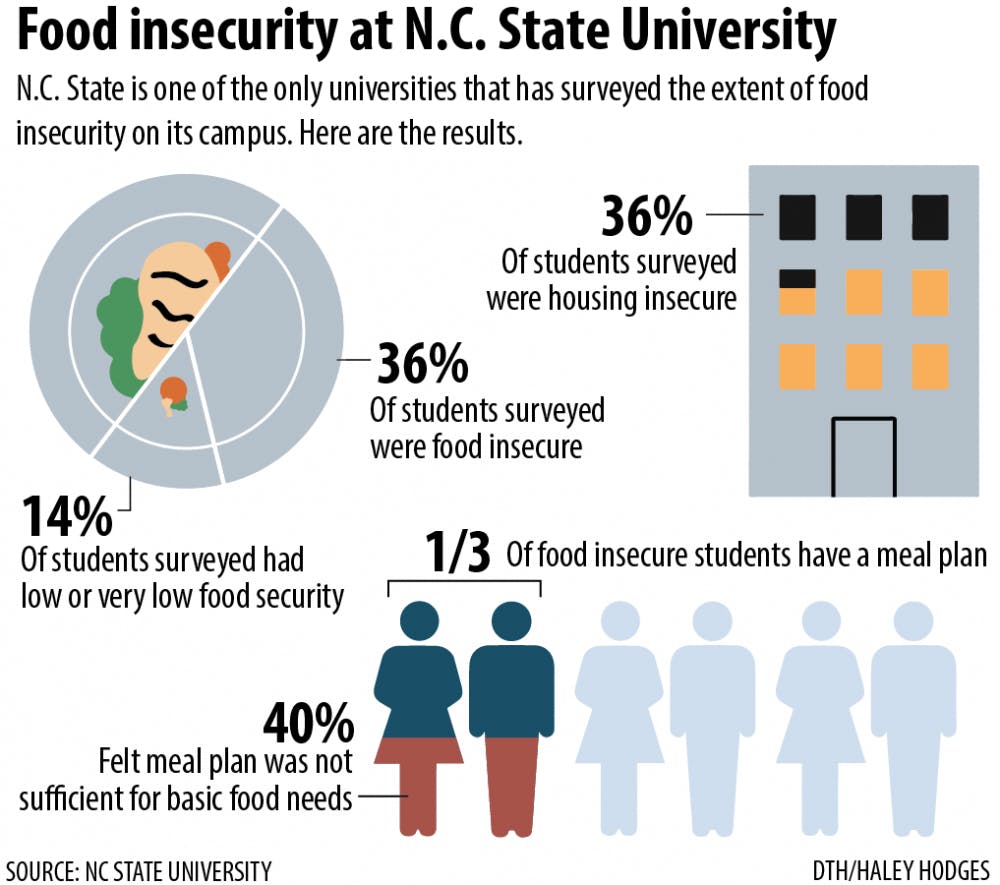

Goldrick-Rab and the HOPE Lab, along with Hernandez, published another study in April 2018, which showed 36 percent of university students surveyed from 20 states and the District of Columbia were food insecure within the 30 days before the study. The study also showed 36 percent of students were housing insecure in the past year, with nine percent being homeless at some point in the past year.

Material hardship, housing and food insecurity are obstacles to college completion, Hernandez said.

North Carolina State University published its own study in February 2018 on the presence of food and housing insecurity on campus. Of those who responded, 14 percent reported low or very low food security in the 30 days prior to the study.

One-third of food insecure students had a meal plan, and 40 percent of those students said their meal plan was not sufficient to meet basic food needs.

The survey also found about 10 percent of students experienced homelessness in the year before the study, and 3.5 percent experienced homelessness in the 30 days before the survey.

After the data was gathered, N.C. State researchers recommended creating an advisory council, coordinating administrative services and funding streams, developing a research agenda and raising awareness.

Desirée Rieckenberg, senior associate dean of students at UNC, said the University was aware of students facing food and housing insecurity, but they don’t know how widespread the issue is because students must self-identify.

She listed several resources the University has for students, including Carolina Cupboard, the Office of Scholarships and Student Aid and the Office of the Dean of Students.

Kate Luck, a University spokesperson, said in an email that UNC is committed to helping all students meet the costs of college and has received recognition for it.

She said no study has been conducted by the University adminstration and the University adminstration does not have any studies on food and housing insecurity "in the works."

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Maureen Berner, a professor in the UNC School of Government, led a study on the impact of food insecurity on UNC’s campus that found 44 percent of the overall population had some level of food insecurity – 22 percent of students were marginally food insecure while 19 percent had low food insecurity and 3 percent had very low food insecurity.

The study also included student responses on how those with food insecurity could be helped. The top answer, at 39.7 percent, was more financial aid.

Other answers were learning how to make a budget (26.7 percent), learning how to eat healthy (25.4 percent) and learning how to cook (26.4 percent).

'Only a Band-Aid'

Studies have suggested many ways for students to help, such as creating programs and educating and advocating for their fellow students.

One effort mentioned in the study is the development of campus food banks. The College and University Food Bank Alliance has 641 members, including UNC, N.C. State and 18 other North Carolina schools.

UNC’s food pantry, Carolina Cupboard, has operated out of the basement of Avery Residence Hall since October 2014.

Kerri Reid, co-donations manager of the pantry, said that they might serve 20 to 30 people each week. She said the pantry is currently working on rebranding themselves to get more visibility.

Reid said the number of students the pantry serves has definitely grown over the years.

“The more that meal plans cost, the more people we see,” she said.

She said that it would be interesting if UNC did a study similar to N.C. State’s so they could then see what groups they serve and who needs more aid.

Students that want to visit the pantry must fill out a demographic survey and a registration form with their name, PID and their Heelmail address. Reid said they don't have data on who uses the pantry.

She said some of the pantry's biggest challenges have been visibility on campus, educating students and helping food-insecure students know it’s OK to come for help.

“Being a student is hard enough,” she said. “We’re trying to alleviate some of the stress in their lives just for them to know, ‘Don’t feel bad about coming here. We’re here to help you.’”

Carolina Cupboard is open every Monday, Wednesday and Friday for four and three hour periods, but students can only go to the pantry once every two weeks.

Thu Le, the executive director of Feed the Pack, N.C. State's on-campus food pantry, said the organization is student-run and student-operated while receiving space and marketing help from the university. The pantry is open Monday through Friday for four hour periods.

She said the pantry doesn’t screen or ask for verification of eligibility from the individuals who use the pantry. Anyone — faculty, staff and students — can use the pantry.

Since opening in 2012, Le said the pantry has had about 4,600 visits. There were about 20 to 30 visits in the first year, and in 2017 alone there were a little over 1,000 visits.

This year, Feed the Pack has already had 1,000 visits.

Le said it’s hard to tell whether the wider publicity and visibility or an increased presence of food insecurity on campus is the cause of the increased visits. She said it’s likely a little bit of both.

She said the pantry can’t really address the core issue of what's causing food insecurity at universities.

“In reality, the food pantry itself is only a Band-Aid,” she said.

She said students that do have these insecurities should know that they’re not alone.

Hernandez said the food pantry movement lacks concrete systematic change from institutions because students are doing the labor.

Regarding education and advocacy, the N.C. State study encourages students to get involved in teaching, training and raising awareness. For example, students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have been working to raise awareness about the expense of meal plans and create opportunities for students receiving SNAP benefits to use those benefits on campus.

To mitigate effects of various emergency needs of students, universities across the country have created student emergency funds. N.C. State and UNC’s funds are generally capped at $500 and can only be used for emergencies and non-tuition-related needs.

Mike Giancola, N.C. State's assistant vice provost in charge of assessing claims, said the fund was created in April 2018 to help financially insecure students in emergencies.

Giancola said it’s critically important for universities to have these funds because there are increasing numbers of students experiencing food and housing insecurities.

“If a student were to experience some sort of challenge, and then their option was to say, ‘Well maybe I need to just drop out of school’ — that hurts the student, that hurts the investment that’s been made both by the student’s family and by the state — in this case being a state institution,” he said.

Hernandez said there are dozens of ways institutions and the government can help students, from regulating financial aid programs to targeting students with the greatest need.

“We need rigorous evaluations of creative approaches across sectors to see how we can help these students," Hernandez said.

@CBlakeWeaver

city@dailytarheel.com