Lilly Mills remembers her sex education class at Asheville High School well. She learned the basics about sexually transmitted diseases and was told that abstinence was the only true way to avoid those diseases.

“Some days we watched videos, but some days he just sat us down and told us stories," she said. “They were all about going to parties, dressing slutty, drinking and getting raped.”

Now a sophomore at William Peace University, she's starting to realize her K-12 education didn't prepare her for the reality of sexual relationships.

In light of recent controversies around consent and sexual assault, many students like Mills are beginning to talk about how their sex education classes weren't comprehensive.

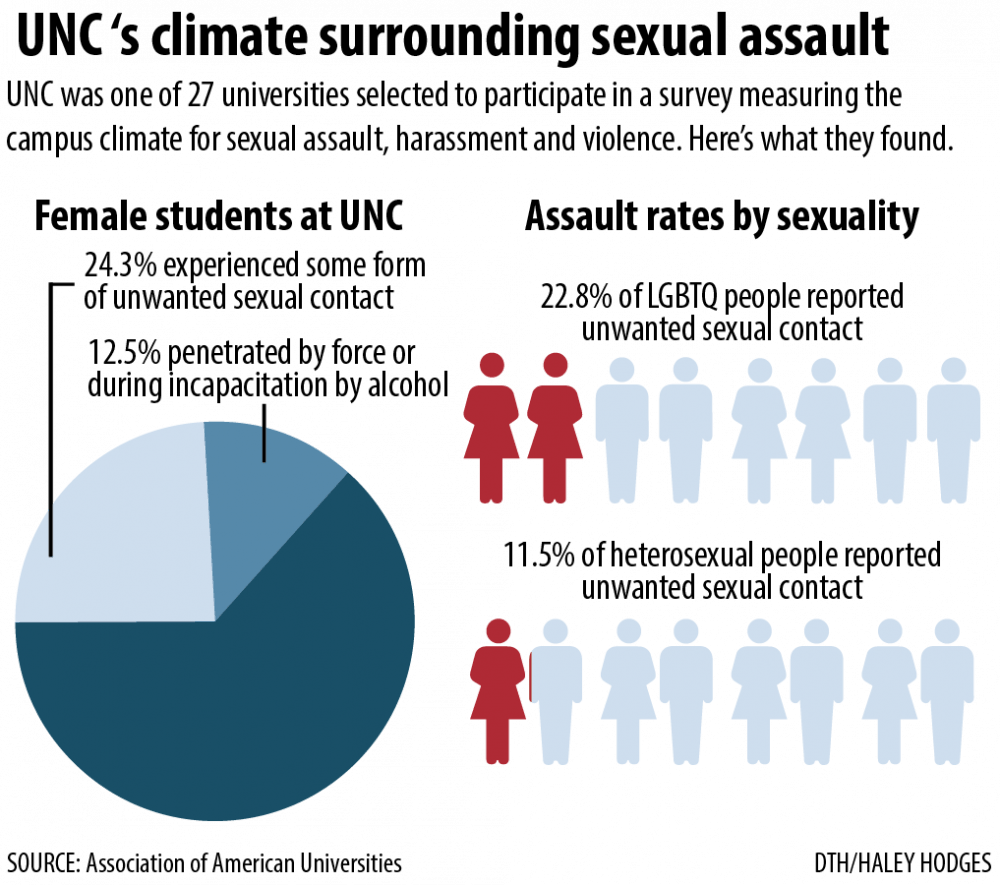

Studies such as the Association of American Universities’ 2015 Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Sexual Misconduct collected data showing just that — over 24 percent of undergraduate women at UNC who responded to the survey experienced unwanted sexual contact, including penetration and touching.

North Carolina is one of only eight states that require the mention of consent in sex education.

North Carolina has specific health and sex education requirements for each grade, but local school districts have a huge amount of leeway in deciding how teachers meet those goals.

Elizabeth Finley is the director of strategic communications for Sexual Health Initiatives For Teens N.C. and works to educate teens about issues of sexual health and relationships.

“One of the legal requirements is that they have to teach about sexual abuse and assault risk reduction, but schools get very few resources to actually figure out how to teach this," she said.