Eventually the felony and the misdemeanor drug charges were dismissed. He received 18 months of probation, pleading guilty to trespassing and a new misdemeanor (contributing to the delinquency of a minor).

But the felony charge had already put Lopez on ICE’s radar.

A database system that spawned in March 2008 under a program called Secure Communities records the fingerprint of every person arrested by a law enforcement agency in the U.S., notifying ICE of the individual's immigration status.

ICE can then issue a detainer, a notice requesting for the person to be held in custody beyond when they would normally be released, giving ICE time for pickup.

Bryan Cox, ICE spokesperson, said deportation arrests are made only after an agent considers both criminal record and other circumstances case-by-case.

The detainer issued the night of Lopez’s arrest to the Wake County Sheriff’s Office cited his now-dismissed felony and his trespass charge. It’s up to each law enforcement agency to fulfill ICE detainers, and Lopez said he knew throughout his criminal trial he would soon face deportation proceedings.

More than a day after the plea deal agreement, ICE took Lopez to the for-profit Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Ga., its largest facility.

“I was mad because I didn’t kill anyone,” Lopez said. “I’m just doing time, and they’re making money. I feel like that’s unfair. I could’ve just waited outside. I’m not even a danger to society.”

Caught up in the system

Lopez didn’t realize the fragility of his DACA status, which offers temporary deportation protection for immigrants brought illegally to the U.S. as children.

DACA permits must be renewed every two years and can be revoked at the Department of Homeland Security’s discretion. With no previous criminal record, Lopez faced trial to see if his two misdemeanor convictions justified a deportation. His DACA permit expired on Oct. 31, and he was still awaiting a decision on his renewal at the time of publication.

Marty Rosenbluth, Lopez’ immigration attorney, said the trials shouldn’t have been held in the first place, and that they contradicted the rules set by DACA because Lopez had not committed a serious crime.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Former Attorney General Jeff Sessions decided on May 17 that judges have no authority to close deportation proceedings for immigrants with protections like DACA.

The U.S. Supreme Court could soon decide the program’s fate. Last week, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals blocked President Donald Trump’s decision to eliminate DACA, which had about 700,000 active recipients as of August 2018.

U.S. Rep. David Price, D-N.C., who represents Orange County and portions of Durham, called ICE’s enforcement an “outrage.”

When he was chairperson of the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security in 2009, the federal budget directed $5.9 billion to ICE, a 6.2 percent increase from the previous year.

“That wasn’t the idea,” Price said. “The idea was to focus on the penal system and people who had been convicted of serious crimes.”

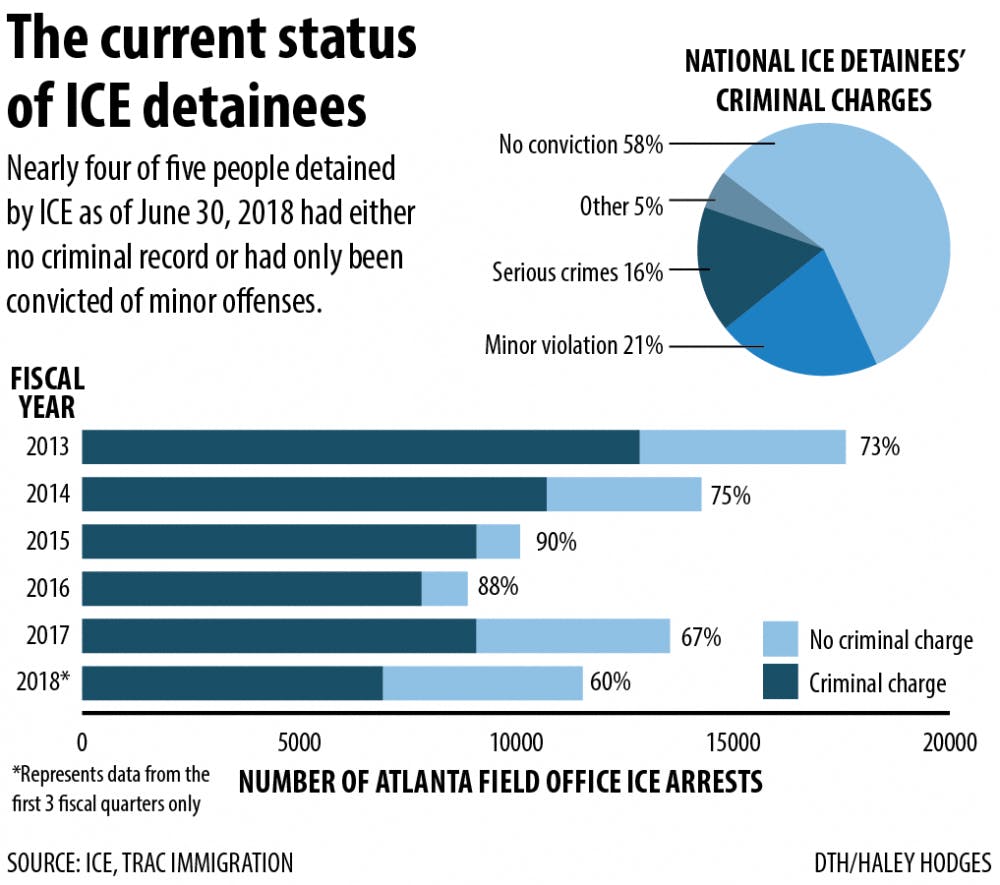

ICE removed 133,551 people from within U.S. borders in 2013. Nearly 41 percent of them had either no criminal conviction or a single misdemeanor conviction by ICE’s standards.

Secure Communities was temporarily replaced at the end of 2014 with a program that limited the scope of ICE’s enforcement. But Trump reinstated it when he took office.

Total ICE deportations in 2017 didn’t reach the heights of President Barack Obama’s first term, but the agency deported 25 percent more immigrants from within U.S. borders than it did in 2016. More than a quarter of the agency’s arrests in Trump’s first year were of people with no criminal convictions.

The solution, Price said, is comprehensive reform that focuses on “dangerous criminals.”

Rosenbluth said he thinks relying on ICE’s discretion doesn’t work.

“Once this huge database of combined criminal and immigration status was created, it’s inherently subject to abuse,” Rosenbluth said.

‘It’s awful’

If deported, Lopez would live in Guerrero, Mexico, with his grandmother, the only connection he has to the state his parents brought him from. Guerrero’s 2017 murder rate was nearly nine times North Carolina’s 2016 murder rate, according to the N.C. State Bureau of Investigation.

Lopez, who graduated from Southeast Raleigh Magnet High School last year, can’t read or write in Spanish. He fears leaving the place he’s grown up in.

“Whatever it takes for me — I don’t care, I’ll do the time,” Lopez said. “However long it takes for me to stay here, I just want to be here with my family.”

Detainees at Stewart are asked to work jobs like cleaning or cooking food for virtually no pay. A lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center and others claimed Stewart deprives detained immigrants of basic needs — like food, toothpaste, toilet paper and soap — and makes them work jobs for $1 to $4 a day to pay for those items.

“It is not prison,” Cox said. “These persons are not being punished.”

A Stewart Immigration Court judge ordered Lopez’ removal from the country on Aug. 17, a decision Rosenbluth appealed. That appeal is currently pending.

“If the Board of Immigration Appeals goes against him, which I highly doubt, my guess is we're going to take it to the 4th (U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals)," Rosenbluth said. "Only because of the legal significance of the case, that they shouldn’t be putting DACA kids into deportation for bullshit like this.”

Lopez, who returned home on Sept. 18, starts classes at Wake Tech next spring. He hopes to one day have a career in cyber-security.

Still, he said he wakes up many nights from nightmares of his cell at Stewart.

“We DREAMers didn’t choose to come to this country and cross illegally,” Lopez said. “We had no choice because we were little kids, and we just want to live without that danger and that fear.”

@bycharliemcgee

special.projects@dailytarheel.com