***

It made sense, but she didn’t want it to.

The falling in the shower. The numb legs when she got out of a hot tub. The back pain. The exhaustion.

She began reading everything she could, and she went into the only mode she knew: doctor mode. The depression came and went, and even today, she gets the waves of anxiety — the fear she won’t have enough time. She tried to keep learning as she always does, she wouldn’t tolerate a life succumbing to this debilitating disease.

She declined quickly, to the point she couldn’t feel her legs. But with M.S., the relapses come and go. She kept working but often had to use a wheelchair or a walker.

Her oldest daughter, Kalynn Smith, remembers a day when Riether had had enough. She told her daughter she was tired of doctors’ appointments, and she was tired of living with M.S.

“I wish pigs could fly!” Smith told her. To this day, they remind each other of their joke, and Riether’s house is filled with flying pig knick-knacks. Smith will tell her mom pigs can’t fly, and Riether will always respond with something like, “You’ll see.”

“She’s never willing to believe anything is truly impossible,” Smith said.

Sometimes the M.S. flare ups would leave her unable to walk, but as a mother of young children, she had to keep going — even if that meant traveling in her hot pink wheelchair.

She remembers riding up to a Tony Young’s All-Star Karate Academy in Atlanta with her three kids to get them lessons. She joked with the instructor that she could be the one to do karate.

“You can do anything with hard work, determination and patience,” Young told her.

These words stuck with her. She told him she wouldn’t be able to drive to the studio weekly, but Young suggested he come to her house. Riether had to fully commit, and for her, that meant turning her home’s basement into a karate studio complete with wall-to-wall mirrors, a punching bag and mats.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, Young worked with Riether in her frigid basement — M.S. patients need cool temperatures for muscle movement. Her first lessons were filled with stretches and throwing punches from the wheelchair.

But each week, Young pushed her a little more.

“Let’s try you standing up,” Young said.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Riether said.

“I gotcha,” he said.

He timed her to see how long she could stay up, and Riether grew to learn that when Young said he had her, he really did.

***

Riether was 40, but she had never voted. She never thought her voice could make a difference. But if she was asked now, she’d say that with a little effort, one can do anything.

It had been six months since she’d went on an M.S. trial drug, and she’d had no relapses. But the provider told her time was up, and that it would take an act of Congress to keep her on the medicine.

That’s when she called then-Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich.

“This is Dr. Riether, and I need to speak to Mr. Gingrich about a very urgent matter,” she told the secretary. The doctor card worked, she put her right through — this would become her favorite tactic in her new political endeavors.

When she got Gingrich on the phone, she introduced herself and told him about her dilemma.

“Well, we have introduced a bill into the House of Representatives called the FDA Modernization Act,” he told her. “Would you like to take a look at that?”

And that was her way in. She has a way with strangers, getting them to trust her, drawing them in. If this act were signed into law, it would allow people to stay on a trial drug until it was on the market.

Riether’s next step was going into the mode she knew best: doctor mode. She started reading about how a bill becomes a law and made a congressional index book. She knew where every congressional member lived, their families and their parties. She was ready to lobby for the bill.

“No one anywhere was like, ‘Go to Washington and change that,’” Smith said. “But that’s my mom.”

Once the bill passed through the House and Senate, it was stuck in committee where members argued over its technicalities. It was right before Christmas, and if it didn't make it through before they left session, the bill would die.

Riether sat impatiently in Gingrich’s office as representatives came and went. She wasn’t intimidated, she didn’t know who anyone was anyway.

A tall man entered the room, and the chatter turned to sudden silence. Riether looked up from her chair as the man looked down at her. It was Erskine Bowles, the chief of staff to the president.

They exchanged greetings, and he asked her why she was there. When she said she wanted the FDA Modernization Act passed, he asked how he could help.

He asked if she’d like to be there when the bill was signed into law.

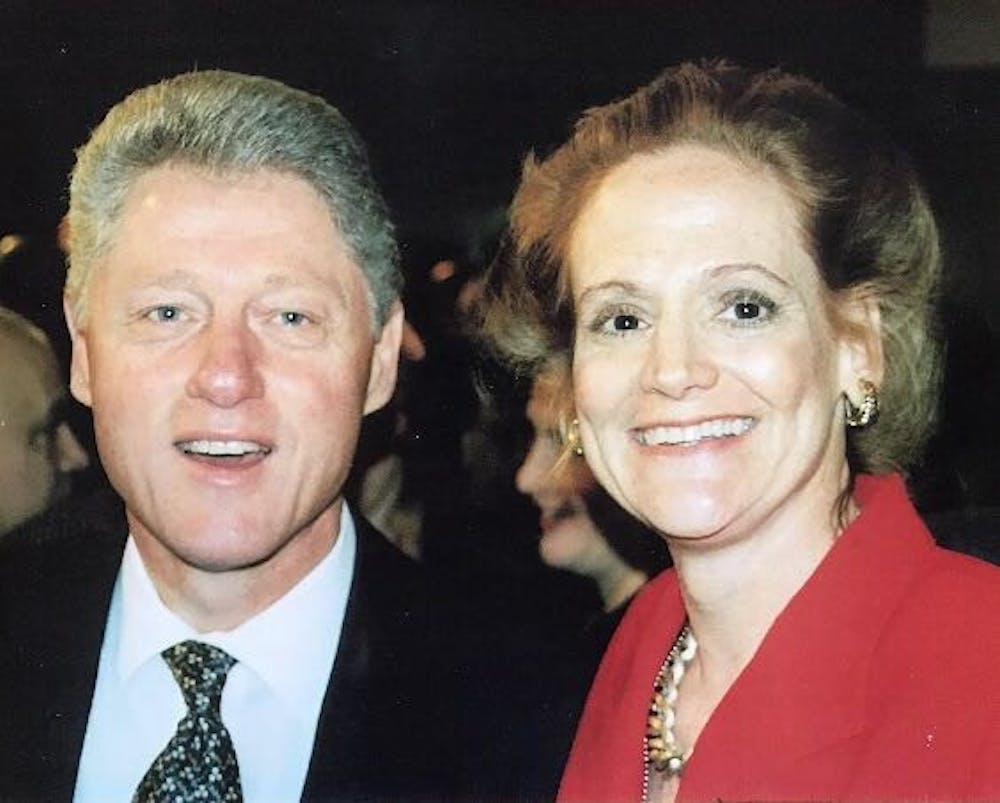

The bill was passed, and Riether left her wheelchair behind to stand on stage with President Bill Clinton when it was signed into law. She even had her own Secret Service guard.

***

In 2002, the stress from caring for her children, working a full-time job and handling her failing marriage led her to take medical leave. She soon after filed for divorce, and the stress added to her deteriorating health.

Her eye sight began declining. The relapses came sooner and sooner over the years, leaving her with bladder issues, fatigue, numbness and muscle spasms. In 2010, Riether filed for disability, what she says was the worst day of her life.

This everyday uncertainty is life with M.S., and Riether tries to take advantage of the good days when they come.

Some days, Riether is having a relapse in the hospital questioning her self-worth — fearful for what her next years might look like.

But other days, Riether is lobbying in Washington or skiing down a black diamond slope in Colorado with her three kids. Or maybe she’s going skydiving with her karate team or, as a graduate of UNC's School of Medicine, volunteer teaching at UNC with her service dog, Kirby.

“I don’t have the answers, but I told each of my kids that someday I want someone to say, ‘you inspired me with your story, and because of you, I didn’t quit,” Riether said.

But it seems like that someday might be now, and for her three kids — she inspired them years ago.

In 1998, her kids nominated her for Mother of the Year. The M.S. Society caught word, and wanted to honor her with the National Achievement Award for the M.S. Society.

She was flown out to Chicago to speak at the society’s annual leadership conference. Thousands of donors from all over the world filled the crowd where Riether spoke about living with M.S., and how it doesn’t define her.

“I want you to listen to the last part of my speech not with your ears, but with your heart,” she told the crowd.

She performed a song in sign language, ending with intertwined thumbs and spread hands, resembling a flying bird.

“A physical ability or disability can never keep us from flying,” Riether said. “You all stand up, fly with me,” she said.

Hundreds of hands lifted above the tables in a wave of movement. And for a moment, “everyone was flying.”

@MyahWard

university@dailytarheel.com