“The conversations at Georgetown have been rooted in the language of Catholicism,” Rothman said. “This is also a school in the middle of Washington D.C., compared to a school in the middle of North Carolina.”

Other public flagships began reconciliation efforts in the early 2000s. The University of Alabama formally apologized for the university’s past ties to slavery in 2004, becoming one of the first in the nation to do so. Former Chancellor Carol Folt apologized in 2018, two months after protestors toppled Silent Sam.

“What UNC is now is what UA was in 2004,” Hilary Green, UNC alumna and associate professor of history at Alabama, said. “We didn’t have people walking on campus, but we had harsh media attention.”

As a student, Green remembers taking alternate routes through campus to avoid walking past Silent Sam. She hasn’t donated to her alma mater because of the politics surrounding the monument.

“There was a failure of leadership in Raleigh and a failure of leadership in Chapel Hill,” Green said. “They are giving space to people who don’t have the heart of the institution and who don’t care about the most valuable stakeholders.”

Alabama universities are exempt from the Alabama Memorial Preservation Act of 2017, which requires local government to seek permission before renaming or taking down historical monuments and buildings.

Green said the exemption was relatively unknown until the university trustees rapidly removed the Culverhouse name from the law school. The board of trustees removed the name after Hugh Culverhouse Jr., who donated $21.5 million, supported boycotts against the state after it passed restrictive abortion laws.

"The Board and the current community has great power in changing the landscape, if willing," Green said.

The University of Virginia is wrapping up its President’s Commission on Slavery and the University. Since 2013, the commission released a final report, began plans for a memorial and expanded the association, Universities Studying Slavery. UNC joined the group in 2016.

Kirt von Daacke, the co-chairperson of the commission, said they have had full support from the university's president and the University of Virginia Board of Visitors for initiatives over the past six years.

“Because of current events, the protests and just watching this unfold, you’d find many people in Charlottesville, when we watched Silent Sam get torn down, be in full support of that,” von Daacke said.

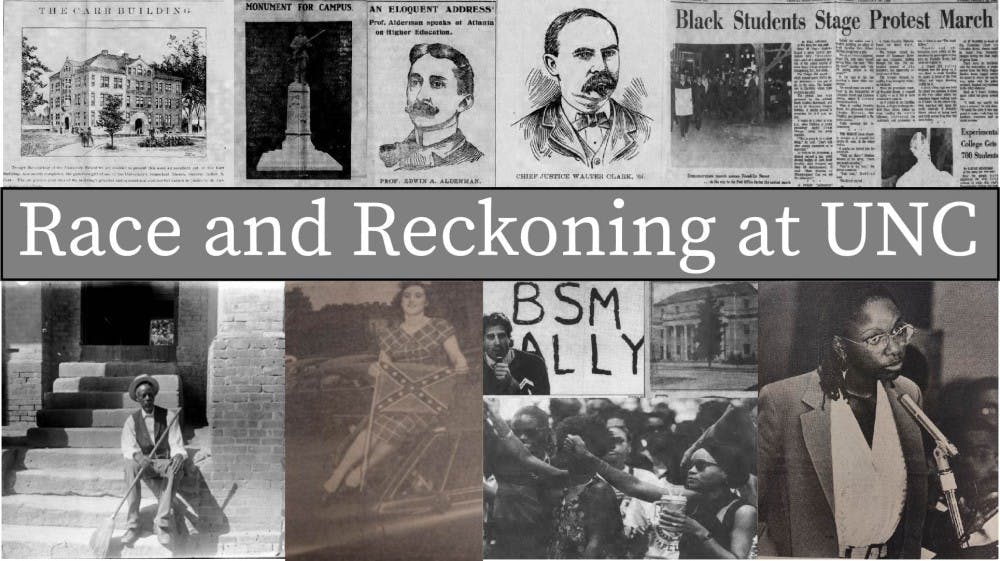

In August, interim Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz announced the formation of the Commission on History, Race and Reckoning. It comes the same year as the Reckoning: Race, Memory and Reimagining the Public University initiative, designed to facilitate discussions about UNC’s racial history through a series of 18 classes.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Guskiewicz said the commission will be larger than the History Task Force, which was composed of a few members. He said it will be composed of faculty studying southern history, staff members, students and possibly alumni.

“I think it’s meaningful with the campus community and look towards the future, that we’re doing it based on what we can learn through this commission, just as some other places have done,” Guskiewicz said.

Green said UNC professors are leaders in reckoning initiatives throughout the South. The exhibition “Slavery and the Making of the University” is available online, and used to be a physical exhibition at Wilson Library from 2005 to 2006.

“UNC has trained a lot of scholars who are at these institutions leading these fights,” Green said. “Who are the leaders and look at the degrees? UNC and UVA have had a wider impact that has added to the conversation on how the universities have to reconcile.”

However, Hinson said optics played a large role in the recent moves to reckon with UNC’s past. The protests surrounding Silent Sam have affected the University’s reputation.

In the end, Hinson said it’s the political considerations of the boards and the legislature that will affect the future of these programs.

“I think just as we had a long history where (the BOG’s interventionist role) wasn't as overt, it may well be that in other states, they're still enjoying a moment,” Hinson said. “In our state, we're not.”

@ramishahmaruf_

university@dailytarheel.com