“The nature of historical records very much privileges certain voices,” Newhall said. “Most of our historical records from the 19th century were produced by white people, and these are white people with particular world views, particular biases, values.”

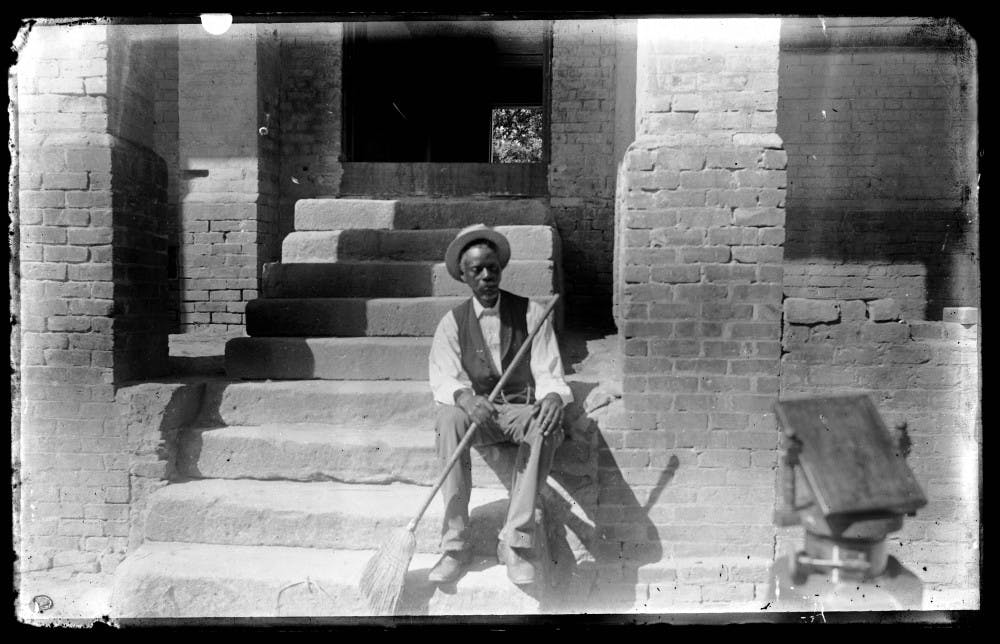

Beyond constructing the University, slaves played crucial roles in everyday life on campus. They shined students’ shoes, made their beds, kindled fires in bedrooms and cleaned the dormitories and recitation halls. Slaves were also responsible for emptying the “slop buckets” used in lieu of toilets.

Students were charged a yearly fee for “servant hire,” and those who were wealthy often brought personal slaves to college until an 1845 ordinance from the Board of Trustees forbade this. It was also common for students to make additional payments to the University financial administrator and hire slaves to perform service outside of regular duties.

History professor James Leloudis, who teaches one of the “Reckoning: Race, Memory and Reimagining the Public University” courses, said the vast majority of people know little about the role of slavery on campus due to their lack of research.

“We’ve known for a long time that the stories are in the archive,” Leloudis said. “But really no one’s made a really systematic effort, scouring the archive and trying to build a story from that research about the many roles of enslaved people on this campus.”

The initiative includes 18 courses across varied disciplines and encourages the discussion of heritage, race, post-conflict legacies, remembrance and reconciliation within the context of U.S. and global histories. Leloudis said this is a good beginning, but there is more work to be done.

“I think we have to be careful not to rush the reconciliation piece without the truth-telling. There’s an awful lot of truth yet to be told,” Leloudis said.

A large part of this truth is acknowledging that the University directly profited from the sale of slaves.

When the North Carolina General Assembly chartered the University in 1789, it gave the Board of Trustees rights over property escheated to the state. If someone died without legal heirs, University attorneys could sell their property and turn profits over to the Board of Trustees. This property often included people.

Selling slaves earned the University a significant amount of income. The sale of Dorothy Mitchell’s slaves in the early 1840s yielded $2,832.10, which would be equivalent to $69,673.50 in 2018, according to West Egg Inflation Calculator.

Ellison Commodore, a current sophomore, did not know the University sold slaves. Although he was not surprised by this information, he said it made him feel weird.

He said UNC should be doing more to educate students about the University's history.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“Being an African American at UNC and all the controversies like Silent Sam and learning more about the history of UNC, I think it’s really important to recognize that and find ways in which we can make the campus more inclusive and more comfortable for different groups of people, people like African Americans and such,” Commodore said.

UNC's past echoes the history of other places in the South, especially regarding the control and abuse of Black bodies. University professors whipped their slaves while slave codes, night patrols and hunting parties restricted slaves throughout Chapel Hill.

Nevertheless, slaves ran away from trustees and professors, defied their owners during whippings and resisted their bondage in other ways.

George Moses Horton, a local slave who taught himself to read and write, sold poems to college students to give to their sweethearts. In 1829, he published “Liberty and Slavery," the first known poem of a slave protesting his status, and later wrote the first book published in the South by a Black person. Horton Residence Hall is named after him.

In the eyes of some students and professors, such memorials are a good place to start, but not enough on their own.

“It’s not quite enough to say 'OK sorry,' tick that box and move on,” Leloudis said. “But there is a much deeper and more profound and far more challenging and lengthy conversation we need to have as a community.”

@ellieheffernan9

university@dailytarheel.com