Frida Kahlo’s art and fame were once eclipsed by her more acclaimed husband, Diego Rivera, as evidenced by the Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera and Mexican Modernism exhibit from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh.

Frida’s image today is a symbol of feminism, Latinx pride, beauty, defiance and resilience. Her fame has far surpassed what it was in her lifetime, and overtaken Diego’s own legacy.

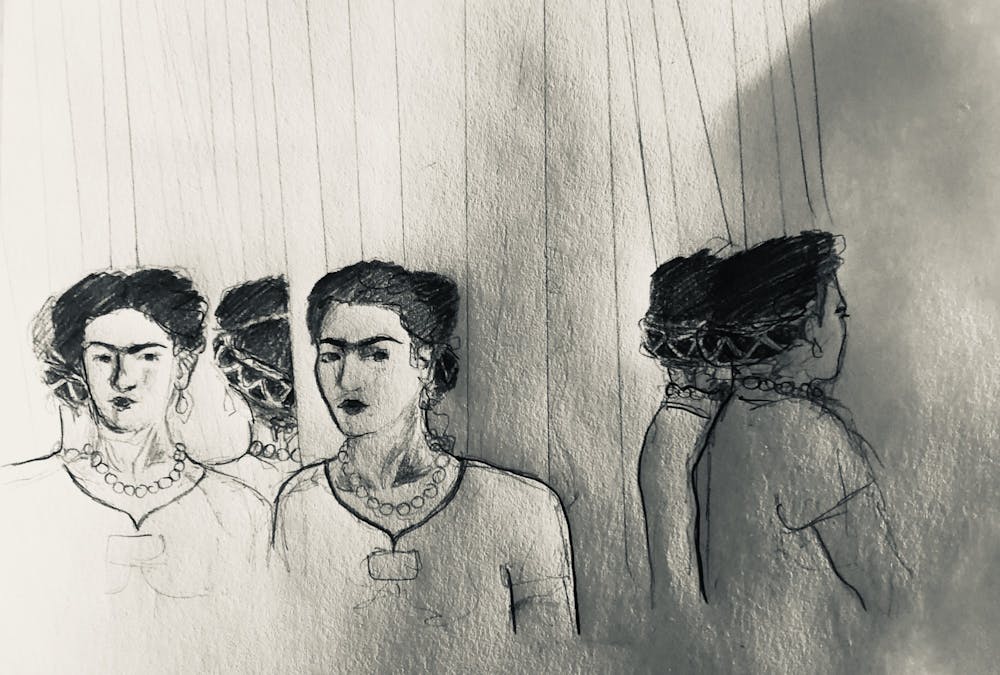

Interestingly, much of Frida’s fame comes from her frequent casting of herself as the subject of her art — self-portraits comprise nearly a third of her work. This was driven both out of necessity, due to her frequent confinement to medical bed rest, and because she felt like she knew herself better than she knew anyone else.

With this seemingly larger-than-life figure, then, how much can we really separate art from artist? Or is this image of the artist itself an illusion that does not perfectly align with the real person?

The vulnerability she shows in her art, drawn from the physical pain she endured through the loss of miscarriage, leads viewers to feel like she has let us in and allowed us to see the most intimate parts of her.

Frida’s self-portraits never feel voyeuristic, though. She stares us down with her self-possessed eyes. She shows us what she wants us to see.