The BOG was created after the General Assembly consolidated the UNC System in 1971. At this point, Democrats were in control of the state legislature and had been since the 1800s.

Particularly in a state that voted for President Barack Obama in 2008, the election was a resounding call for change. But voters at the time likely didn’t know just how much would be altered after that November.

Though the Democratic party did not always look the same as it does today, it had a stronghold on the state until 2010. That midterm election saw victories for Republicans nationwide, said Mitch Kokai, senior political analyst at the conservative John Locke Foundation. At the same time, he said it’s not that simple.

“It’s important to note that the vote in North Carolina to support Obama in 2008 was an aberration in terms of recent presidential elections in North Carolina,” he said.

The state had only voted for Republican presidents since 1980, and he said Obama’s election ended up having national consequences that had a ripple effect on state and local issues,

especially with the controversy over the Affordable Care Act. The state was also still struggling with the burden of the Great Recession, and Gov. Bev Perdue raised taxes to maintain the current spending levels.

That, combined with the fact that Republicans challenged Democrats in several districts for the first time in years, turned the electoral tide in the state, Kokai said.

What happened after?

Once the Republicans were sworn into office in 2011, they were “ruthlessly effective,” said Rob Schofield, director of N.C. Policy Watch.

With Republicans at the helm, they sought to carry out the conservative policies they had been advocating for the entire time, Schofield said.

This included cutting the tax rate while at the same time changing priorities for social spending. The state started emphasizing school choice and charter schools while cutting per pupil spending on education. Though the state has risen in terms of teacher pay, Schofield said the party has had an ideological drive to cut back on the government's influence.

Republicans also took control during a consequential year. Redistricting occurs every 10 years with the new census results, so the party had the potential to permanently shift the balance of power, said Mac McCorkle, a public policy professor at Duke University.

“They got a majority in 2010, and the way I look at it is that their gerrymandering then gave them a supermajority which was artificial,” he said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Having a majority, and then a supermajority, meant Republicans in the General Assembly could more easily pass their own proposals — especially within the state’s higher education system.

How did the BOG change?

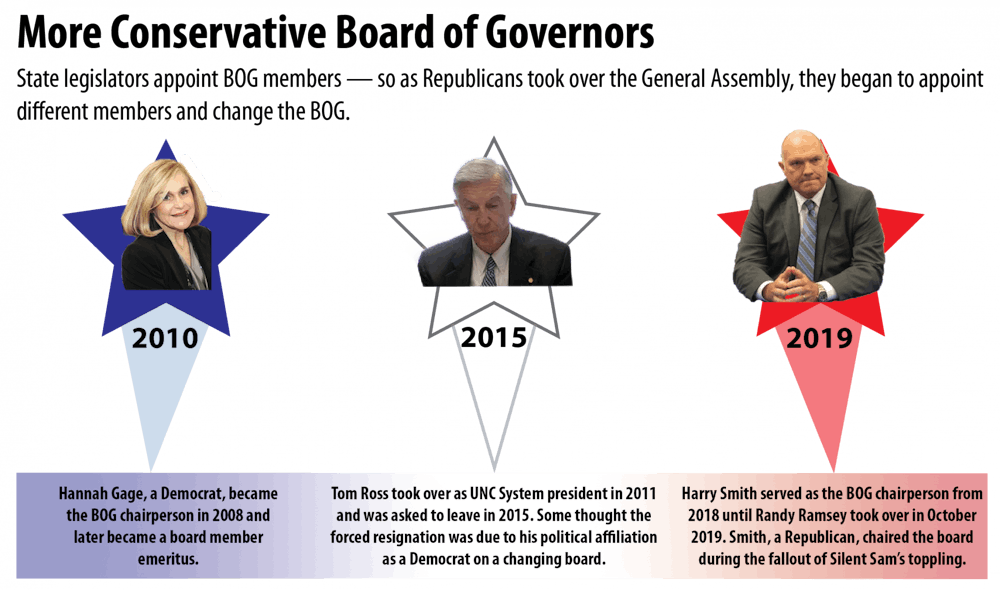

The sitting BOG members’ terms ended in 2011 and 2013, giving the legislature a chance to shake up UNC System leadership. Now, almost 10 years later, there are no self-identified Democrats sitting on the Board.

T. Greg Doucette, now a criminal offense attorney, had a position on the BOG from 2008 to 2010 as its student representative. He said at the time, he was one of few Republicans on a majority-Democrat Board.

Doucette said during the transition time between 2011 and 2013, when some members were at the end of their terms and others had just been appointed by the General Assembly, there was a “stark contrast.”

“Not so much in politics — that was there as well, but University politics isn’t really partisan per se,” Doucette said. “It’s more on should the University be able to run themselves or something where the politicians in Raleigh be able to have a thumb on the scales and decide what they do.”

Schofield said the new members of the BOG perceived their roles differently.

“The folks who have been in charge, they have a very different view of what progress means, and they have made in particular higher education one of their targets,” Schofield said.

Ross said the shift affected his job not necessarily because of politics, but because the significant turnover pushed out people who had been on the BOG for a long time and had institutional knowledge about the complexities of the system.

New members, Ross said, do not always have the background, knowledge and experience they need to lead the UNC System.

“Losing a large number of board members at one time I think created a Board that had a learning curve, and it created, therefore, demands on my team and on me to help them climb up that learning curve quickly,” he said.

Deep post-recession budget cuts to the UNC System added to the tension of a BOG heavily made up of new members. The BOG allotted an average 15.6 percent cut across the system, with UNC-Chapel Hill’s budget getting slashed almost 18 percent.

“That put stresses on the system that had not been there previously, and I think that changed the focus of the administration as well as many of the board members,” Ross said.

McCorkle said since taking power, Republicans have come off as either indifferent or even hostile to higher education. Republican legislators began using their power to appoint conservative members after 2010, and some current BOG members are former legislators themselves.

Kokai said he thinks this isn’t necessarily a change, however.

“Once Republicans took over, they had the chance to appoint Republican lobbyists and Republicans who were well-connected,” he said. “The type of people getting appointed were the same except the letter after their name indicating their party.”

What comes next?

Though many observers note the faults of a system where the legislature appoints the BOG, most do not see a realistic alternative.

“The BOG has always been appointed by the General Assembly, I think it’s just been a fear in recent years because of the partisan divide between faculty, local students at the university campuses and the board of governors,” Kokai said.

McCorkle and Schofield said it would make more sense for someone with a statewide office like the governor to have a say in appointments, but they said they think this kind of overhaul is unlikely because it would require a vote from the General Assembly.

Holden Thorp, who served as UNC-Chapel Hill's chancellor from 2008 to 2013, saw firsthand the shakeup of the BOG as the legislature changed party. Thorp said having the General Assembly appoint the BOG is not a great system but one most states have.

"I don’t think North Carolina is going to be the first state to stop having political folks appoint the governing board for the University," he said.

Though BOG appointments may not be at the top of voters' minds as they go to the polls in 2020, their votes could greatly impact higher education in North Carolina.

With both the state legislature and congressional maps for North Carolina up in the air, 2020 could be another consequential year like 2010. Of the members who currently sit on the BOG, about half have terms ending in 2021 and the rest have terms ending in 2023. This means the party in control by the end of the 2020 election cycle will have the power to potentially change the course of the BOG again.

“Everything is war," McCorkle said. "Everything is a battle in NC."

university@dailytarheel.com | city@dailytarheel.com

Anna PogarcicAnna Pogarcic is the editor-in-chief of The Daily Tar Heel. She is a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill studying journalism and history major.