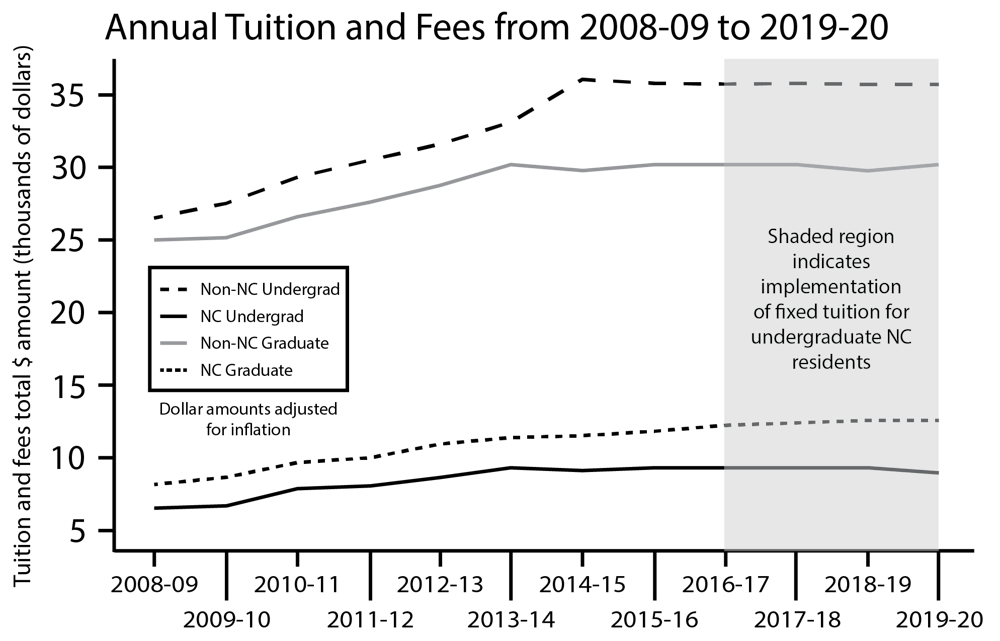

Since the 2008-2009 school year, in-state undergraduate students have seen tuition increase by 59 percent, adjusted for inflation.

For in-state, or resident, graduate students, the change jumps to 77 percent. But since 2017, resident undergraduates have seen a decline in tuition rates, while all other groups have relatively constant tuition rates.

The overall tuition increases align with a documented trend in higher education since the 1980s. From 2007 to 2009, America experienced the Great Recession, which Vice Chancellor of Finance and Operations Jonathan Pruitt credited with the largest tuition increases of the past decade.

“Especially when you look at the amount of student debt, I think young people are starting to figure out that’s not sustainable and the pressure that puts on them after they finish school,” said North Carolina Sen. Terry Van Duyn, D-Buncombe. “They’re questioning whether or not higher education is a sound economic investment, and we don’t want young people thinking that way.”

Although the costs appear to level off around 2016 for all groups, paying for college remains a key policy priority for many members of the General Assembly. Tuition is approved by the legislature, but UNC plays a large role in setting the rates.

This process begins at the Tuition and Fee Advisory Task Force, of which Pruitt is a co-chairperson. After reviewing and proposing tuition and fee increases, the chancellor and executive vice chancellor and provost finalize the tuition for the Board of Trustees.

At the Nov. 20 BOT meeting, the proposed tuition and fee increases for the 2020-21 school year were presented for final on-campus approval. Over the next four months, the Board of Governors is set to approve the tuition and fees, pending final approval from the legislature.

Members of the legislature have voiced concern over the tuition increases, including Sen. Erica Smith, D-Beaufort, and Van Duyn. This concern is prevalent at the national level as well, evidenced by Pew Research Center report showing “improving the educational system” at the top tier of public priorities.

“What we have done over the years is we have shifted the burden of paying for the universities from the legislature to the students,” Van Duyn said. “When I went to college from 1969 to 1973, you could earn enough in a summer job to pay tuition and fees at a public university.”