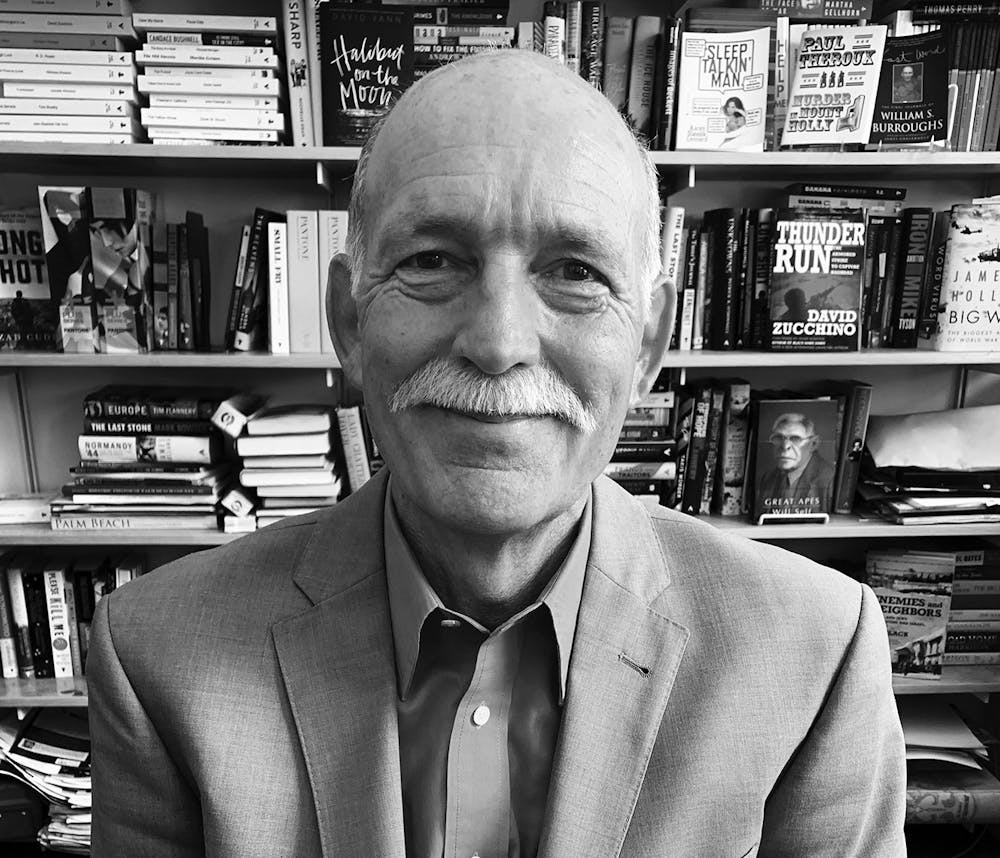

When Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Zucchino attended UNC, his introductory journalism classes were conducted on typewriters.

While journalism students have traded typewriters for laptops, Zucchino said one thing that connects his past to students’ present is that buildings on UNC’s campus are named after white supremacists — the figures of his new book, “Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy."

On Monday, Zucchino returned to his alma mater to discuss his book and connect the historical legacy of white supremacy from 1898 to today.

Zucchino was joined by associate professor Trevy McDonald and students Excellence Perry and The Daily Tar Heel Director of Investigations Charlie McGee. They spoke for the Nelson Benton Lecture Series, named after the UNC graduate and broadcast journalist. In her opening remarks, Dean Susan King credited Zucchino with his history at The Philadelphia Inquirer, Los Angeles Times and currently, The New York Times.

“He has been at the center of the biggest international stories of his time, and yet he always comes back home to North Carolina,” King said.

“Wilmington’s Lie” tells the story of the coup in Wilmington, N.C. in November 1898. Zucchino said that in 1898, Wilmington was a rarity because of its majority Black population and its multi-racial government. Having Black citizens in positions of power was a threat to white supremacy, he said.

In November 1898, white supremacists overthrew the government, killed over 60 Black citizens and appointed the rulers of the mob to government positions. Zucchino said no one was prosecuted for this massacre. Reporters covering the massacre were largely white, and a white narrative was constructed that framed these events as a “race riot.”

“It was not a race riot, it was a racial massacre,” Zucchino said. “It was a planned murder spree and a racial revolution. In fact, it was the most successful and permanent violent overthrow of an elected government in American history, there has never been anything like it before or since.”

Zucchino said the goal of this massacre was not limited to overthrowing the government in Wilmington. Rather, the goal was to prevent Black men from voting and holding public office in the future.