On Oct. 7, 1918, the concerned father of a UNC student wrote a letter to University President Edward Kidder Graham. He wanted Graham to notify him if his son got infected by a strain of influenza — the Spanish flu.

“Should our son John come down with influenza,” wrote the parent, “and his condition in any sense be serious, please notify of same (sic) by wire at my expense.”

The 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed between 20 to 50 million people worldwide, is considered one of the deadliest epidemics in human history.

While the virus was relatively mild during the spring of 1918, in the fall a deadlier second wave began. By September, it spread to North Carolina.

“There are thirty cases in the hospital,” Graham wrote back to the parent on Oct. 19. “This shows a steady decrease from the maximum of about one hundred and thirty. There are twenty in the convalescent building. These men are virtually well; they are simply being detained there as a precaution.”

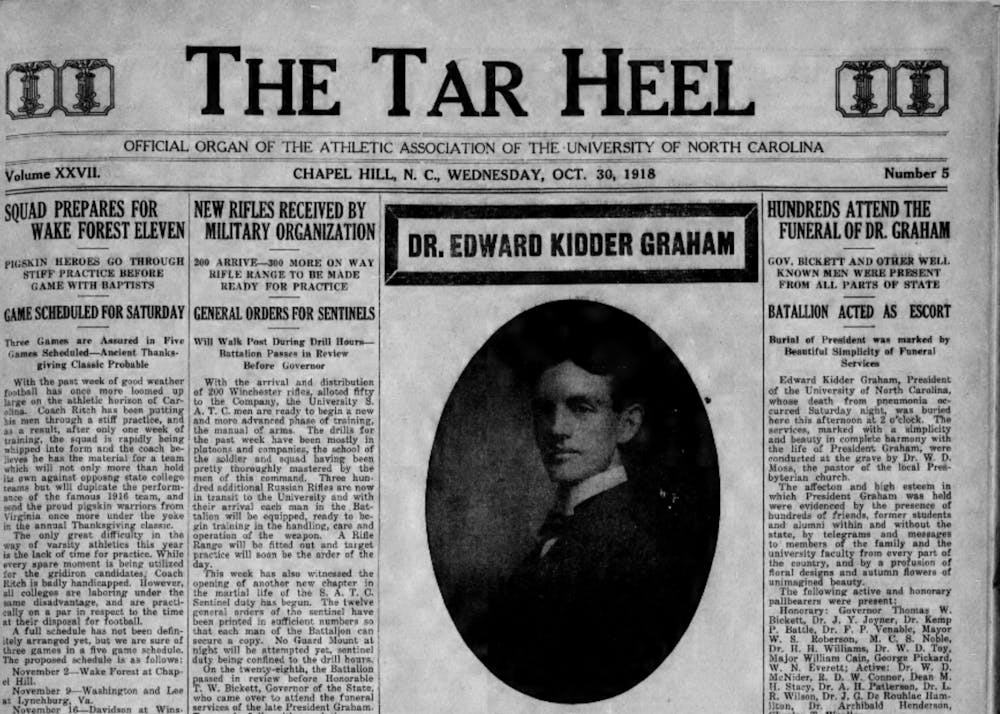

The campus was quarantined in October, but just two days after sending the letter, Graham himself fell ill, according to a blog post from University Archives. As was typical for those infected during this second wave, he developed pneumonia as a secondary infection — and died in less than a week.

All classes and military drills were canceled the following day out of respect for the president, according to the archive post.

On Oct. 31, Marvin Stacy assumed leadership of the University. Three months later, however, Stacy also became infected with the flu, and died of pneumonia like his predecessor, according to University Archives. When the pandemic finally began to wane in the spring of 1919, over 500 UNC students had been treated in the infirmary and seven had died as a result of complications with the illness.

The University is now facing another public health threat — the spread of COVID-19, known as the novel coronavirus. In response, UNC has implemented cautionary measures such as going remote for most classes, canceling campus events for more than 50 attendees and prohibiting University-affiliated travel outside North Carolina.