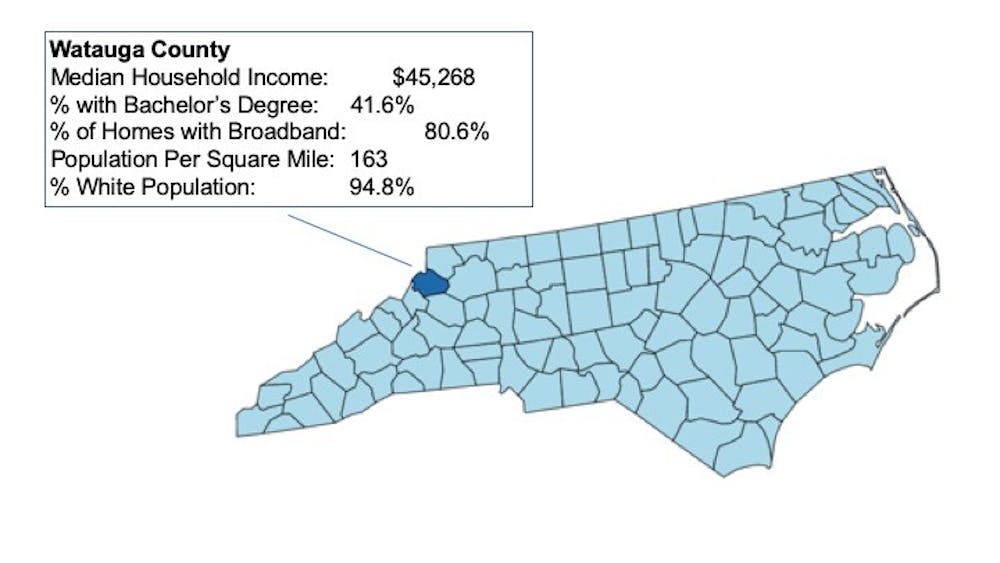

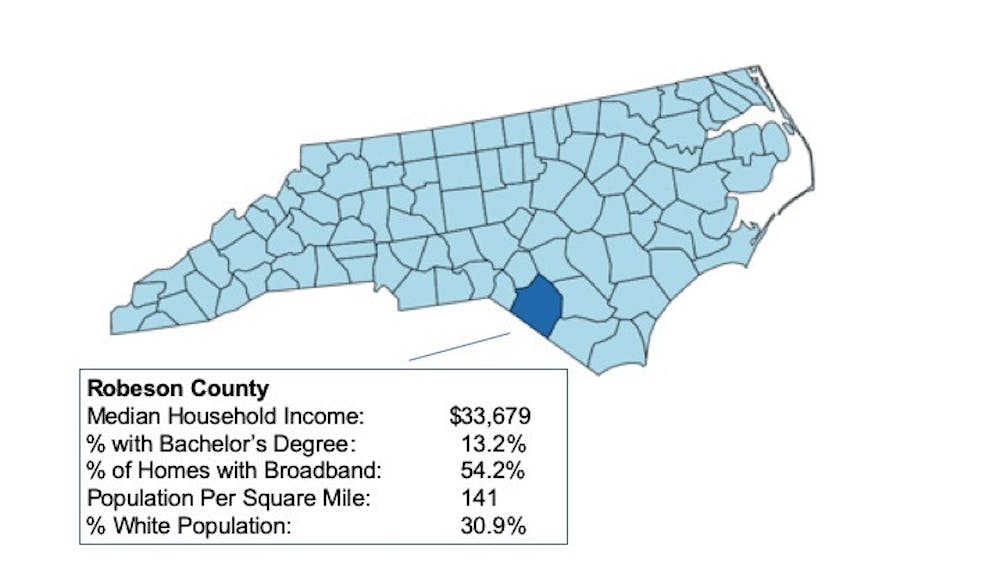

For two North Carolina counties, Watauga and Robeson have little in common.

Until recently, Democratic candidates could count on the votes in Robeson, and Republican candidates could count on Watauga.

But in 2016, they switched.

This divide, however, followed a pattern — in general, the 2016 election saw counties across North Carolina shift their vote based on divisions of class. And Watauga and Robeson have long sat on opposite ends of several demographic spectrums.

Just over 13 percent of Robeson County residents hold a bachelor’s degree, while nearly 42 percent of Watauga residents hold one. Out of 100 North Carolina counties, Robeson has the smallest percentage identifying as white, while Watauga is one of the least diverse. And 80.6 percent of Watauga residents have broadband in their home compared to just 54.2 of Robeson County residents.

With competitive elections up and down the ballot in November, these counties are a microcosm of two faces of North Carolina voters: Robeson County has had to grapple with widespread poverty and low education levels. And for the most part, Watauga has not.

Between the 2012 and 2016 elections, Watauga County shifted towards Democratic candidates and Robeson County shifted towards Republicans.

‘The old mountain folk way of doing things’

Stacey “Four” Eggers IV was born and raised in North Carolina’s high country in the Town of Boone, the seat of Watauga County.

“I’ve sometimes joked that my folks have been here before there was even a road to get here,” he said. “So I'm not quite sure how they arrived in these mountains or why they would want to live on top of a cold, snowy, windy mountain when there's farmland around for the taking.”

Eggers is part of multiple generations of lawyers. He attended Appalachian State University for his undergraduate degree and now sits on its Board of Visitors.

“The community has had a very seamless back and forth with our college that provides a lot of great arts and cultural opportunities that we probably would not have if we didn't have our university right here," he said.

Relative to North Carolina as a whole, a high proportion of Watauga County residents hold a college degree.

Eggers said the growing pains of the Town of Boone and Watauga County are much like the trends seen in college towns across the country.

“One of the problems that you run into with growth is when you reach a certain point it becomes really easy for folks to silo themselves," he said. "And it can fall into ‘This is my community and this is my group.’”

Joe Furman has served as director of the Watauga County planning and inspection department since 1984. He said he’s seen Boone flourish in his time there.

“It’s much more vibrant than it was,” he said. “The sidewalks used to roll up at five. But now there’s nightlife. It's evolved from kind of a small rural town to more of a more urbanesque downtown.”

Eggers said this development has changed the channels of discourse in the town.

“It used to be that the way people would get their news, everybody would walk down to the local drugstore. And that was the place to have lunch,” he said.

And while Watauga has voted for Republican candidates in seven out of the last ten presidential elections, Furman said the county’s political bent has never been set in stone.

“In my time here it has flip-flopped back and forth," he said. "The town is overwhelmingly Democratic, the county, rural area the county is generally Republican. It tends to balance each other off.”

Compared to the counties around it, Watauga is an island of elevated income and education. Furman said he’s hopeful the university will continue to drive those factors for the county.

“Hopefully, we'll be able to attract some of the talent that leaves to stay here and perhaps grow and create some jobs," he said. "That's a big challenge for us."

But the more urban college town of Boone and the more rural county of Watauga are not synonymous. Eggers said the balance between the conservative rural areas and liberal towns make it an important data point on the state’s political landscape.

“Watauga is a very good bellwether, so to speak,” Eggers said. “If I were watching which way the state or the nation will go, I think Watauga county is a good example area because we're right at about 48th or 50th (out of 100) as far as population size across North Carolina. We have more unaffiliated voters than we have Republicans or Democrats."

King Street in Downtown Boone, N.C. Photo courtesy of the Boone Watauga County Tourism Development Authority.

Watauga is nearly racially homogenous, with almost 95 percent of its residents identifying as white. But with more than 40 percent of the population holding a bachelor’s degree — the fifth highest of any county in the state — Watauga experiences its social fractures along different lines.

“You do get a little bit of that tension — kind of the old mountain folk way of doing things versus folks that have moved in recently, and have different backgrounds and different experiences.," Eggers said. "Part of that, I think is there's always some concern about the fear of the unknown.”

But Eggers said this is not a new phenomenon.

“Growing up in the Town of Boone and riding the bus home in the afternoon, I’d hear my friends talking about local politics and national politics," he said. "And riding across town on the bus, I was left with the impression that my family was woefully out of step with the rest of the community and the rest of the nation as far as who we were going to vote for for President. Because listening to the conversation on the school bus, it was readily apparent that Walter Mondale was going to absolutely clobber Ronald Reagan," he said.

But in 1984, 64.3 percent of Watauga County and 61.9 percent of North Carolina voted for Reagan.

“It taught me an important lesson of being careful about not living inside a bubble,” Eggers said.

‘Bottom of the totem pole’

For 24 years, Donnie Douglas was the editor of Robeson county's local newspaper, The Robesonian.

“In many ways, the story in my mind about Robeson county is why we haven't done better,” he said. “You know, somebody once told me, ‘Put two babies in a crib, they get along fine. You put a third one in there, they don't,' referring to the tri-racial area.”

According to U.S. Census data, Robeson County's racial makeup is 31 percent white, 24 percent Black or African-American, and 42 percent American Indian, making it the county with the lowest percentage identifying as white.

Robeson County sits in the Sandhills region on the border with South Carolina. For years it was an agricultural stronghold for the tobacco industry. But tobacco jobs were replaced by textile manufacturing jobs in the 1990s, and manufacturing jobs were eventually replaced by service jobs along the I-95 corridor.

“Although our unemployment rate, pre-coronavirus, like most places was really good, the poverty rate wasn't because the jobs that replaced the manufacturing and tobacco jobs are service and they're not well paid and not well benefited,” Douglas said. “So now you have several thousand people in the service industry who live paycheck to paycheck.”

Robeson County had the smallest percentage of its population identifying as white in the 2010 census.

Robeson has the third-lowest median income of any county in the state. While Douglas pointed to some successful developments around the county, he said it has been stricken with high poverty and racial division.

“We're a 68 percent or 70 percent minority community that used to be 80 percent registered Democrat," Douglas said. "And we just voted for Donald Trump."

Some may find it surprising that the least white county in the state had the biggest vote swing toward Republicans between 2012 and 2016. It was the first time Robeson had voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1972.

“Well, if they're surprised they evidently live outside the county because it's no surprise what's going on,” said Robeson County Commissioner Jerry Stephens.

Stephens was born and raised in Robeson County and is now the chairperson of the Unified Robeson NAACP’s PAC.

“It's really about, 'What have you done for me lately?' You know, if you keep voting for a party and they're not delivering to your community, why keep voting?” he said.

Stephens said that even while he's seen the Native American population thrive in the area, he feels the Black community has continually been left behind. He pointed to rural broadband access and affordable housing as two major issues facing the region.

“I can't say it’s bad as it was in 1953 or 1960 when I was growing up, but it's still got its challenges," he said. "For the most part, you know, it was the white, Native Americans and then African Americans. Now its Native Americans, then white, and then African-Americans. African-Americans still hold what we call the bottom of the totem pole,” Stephens said.

The Lumbee Tribe's tribal government office, pictured here on Thursday, April 16, 2020, is located in Pembroke, North Carolina. The Lumbee Tribe is a state-recognized tribe in North Carolina numbering approximately 60,000 enrolled members. Most of them live primarily Robeson County.

Harvey Godwin Jr. grew up in Robeson County on the farm his grandfather established in 1909. Today, he is the chairperson of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina.

“Any one group affects the other groups,” he said. “So I see us really working together now to make sure that we're collaborating on a positive level to make sure everybody is at the table and everybody wins.”

One of the major economic obstacles the county has had to overcome is the impact of two major hurricanes in the last three years.

“We've been working since two hurricanes to get back to the poverty level we were at before they occurred," Godwin said. "But I think we're doing better now.”

As agribusiness has made a return to Robeson, Stephens said access to rural broadband internet has become even more vital.

“We do need more for internet access into the county that we don't have, but we were coming along," Stephens said. "We’re striving.”

Godwin said traditionalist values have been the deciding factor that drove many voters to shift from Democrats to Republicans in 2016.

“Our people are very traditional,” he said. “I mean they're Christian people, believe in God, they believe in the value of education. And those things follow them into the voting booth.”

But while Robeson may have a socially conservative bent, Douglas said its politics are also defined by its reliance on social assistance programs.

“As I like to say — and this is said somewhat cynically — we like our checks,” he said. “I mean we're number one in the state in disability, and truthfully welfare is our leading industry."

But one of the most prominent issues Godwin said the Lumbee vote on is the issue of federal tribal recognition, which Godwin said would bring additional health care and housing benefits for the tribe's members.

“For the people, it's more a sense of pride,” he said. “Our people go all over the country and they meet with other tribes across the nation who are federally recognized. And there's always this sense that we're less than because we're not fully recognized and our voice is not fully heard, because we're not fully federally recognized.”

The sway the Lumbee tribe has over state and local politics is not lost on Godwin.

“You're talking about 40 percent of the population of Robeson County is American Indian. It's a big voting block,” he said. “Our people have moved away from being mostly blue 25 years ago, and now the Lumbee vote can swing. It can go red or can go blue which it has in last few election cycles. That's a strength. That's a power to where you can negotiate and bring in things.”

But on top of the economic struggles affecting the county as a whole, Stephens said Robeson’s Black community has had to fight for a seat at the table.

“Politically it’s beginning to be a nightmare,” he said. “It's scary. It's really scary. Sometimes it looks kind of dim, that it's going to get any better. I'm 67 and if it gets better in my lifetime I might buy you two steaks or something, but I'm trying,” Stephens said.

Stephens, Godwin and Douglas all agreed that, although Robeson has had its fair share of challenges, there are many things to be optimistic about.

"I've been here all my life and I wouldn’t be here if I wasn’t optimistic, because we’ve got good people here of all races. But you've got that old mentality that seems to be coming back," Stephens said. "I feel always optimistic because I'm a devout Christian, 40 years. And I haven’t lost hope yet."

With competitive elections from school board to president on the ballot in November, voters’ decisions at the ballot box will undoubtedly be shaped by their shared local experience.

In general, the 2016 election saw higher income, more educated counties shift toward Democratic candidates, while Republicans drew the attention of counties struggling with high poverty and low college education rates.

But while factors such as income and education can serve as good benchmarks for how these areas shift their vote, no county is a monolith.

“It’s kind of, for lack of a better term, a built in sample set,” Eggers said. “We have to be careful not to get in too deep into one area of the sample set versus the other areas because, you know like I said, if you're riding on the right school bus, you're just going to be convinced that Walter Mondale was President of the United States.”

Play around with the interactive graphic to see how various demographic factors affected the vote shift in different North Carolina elections.

@DTHCityState | city@dailytarheel.com

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.