Although the system promises protection, the three survivors say that inconsistencies and deficiencies in manpower and infrastructure at the UNC level, and a too-heavy burden on victims at the state level, left them feeling wholly unprotected by the system.

Interim protective measures

UNC students can request a no-contact order from the University without requesting an investigation by contacting an EOC office report and response coordinator. All student requests must receive approval from a senior EOC administrator, such as Adrienne Allison, UNC’s Title IX compliance director.

An approved UNC no-contact order “will direct one individual to have no contact with another individual,” including but not limited to various forms of in-person, written and third-party communication, Allison said in an email to the DTH on Feb. 4.

A University no-contact order doesn’t appear on the academic or disciplinary record of any student, she stated.

If a student doesn’t abide by a no-contact order, Allison wrote, the EOC office will evaluate whether the contact constitutes retaliation, stalking or harassment, in which case a student can be charged with violating the office’s policy. UNC's Office of Student Conduct is also consulted on an appropriate response, she said.

The University can conduct "traffic pattern checks" for these orders, which Allison described as “an interim protective measure for a student who reports sexual assault, interpersonal violence or stalking to the EOC and who is concerned about the impact on their safety or emotional or physical well-being should they cross paths with the student alleged to have harmed them.”

In most cases of traffic pattern checks, Allison said the EOC office advises students on how to avoid the other student.

“In some cases, the EOC might ask the other student to modify their path to avoid crossing paths with the reporting student," Allison wrote. "In implementing any protective measure before an adjudication of the reported conduct, the EOC balances safety, privacy and access to education programs and activities for both students.”

Over-promised and under-delivered

The EOC office granted Violet a no-contact order in October 2017. But soon after, Violet said, she was informed that when the office contacted her alleged assailant to inform him of the order, they found he'd withdrawn from UNC.

“They came and told me basically that he’d left. So the no-contact order stood, but they couldn’t enforce it if he wasn’t a student,” Violet said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

A year and a half later, when Violet found out through Tinder that he had re-enrolled, she emailed the EOC office to ask why it had not notified her.

In an email response on Feb. 7, 2019, an EOC report and response coordinator said she may have given Violet the false impression that the office could inform her if her alleged assailant were to re-enroll. The coordinator cited the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, as one of the reasons she wasn’t able to notify Violet of his re-enrollment.

FERPA allows schools to disclose, without consent, public directory information, including a student’s name and dates of attendance. However, schools must notify students of this information release beforehand, and students and their parents can opt out at any time, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s website.

The coordinator told Violet in her February 2019 email that a miscommunication may have obscured the fact that she can only conduct traffic pattern checks upon request.

"While I am happy to perform the traffic pattern check and relay what information I can, due to my caseload and the number of folks my office interacts with, we can only do these checks when explicitly requested," she said. "In other words, due to my schedule I’m unable to set a reminder every semester and conduct this check without request from a student."

The coordinator apologized for the miscommunication and any negative effects it may have caused. Violet said she felt the University had pushed responsibilities onto her.

“The gist of what I got from them was, ‘You should’ve been asking for traffic pattern checks. It’s not on us,’” Violet said.

Violet officially requested an investigation of her incident from the EOC coordinator on March 22, 2019. The coordinator informed her in a March 29 email that she’d be introduced to investigators the following Monday.

“Thank you again for your patience as the EOC process can often take some time,” the coordinator wrote.

In May, the EOC office said her alleged assaulter had once again withdrawn. Violet asked if the office could flag his account to notify her if he re-enrolled.

On June 25, Violet's gender violence services coordinator — someone who works in the Carolina Women's Center who works to provide "confidential support and advocacy" for members of the University community affected by gender-based violence — asked the EOC for an update on the request to flag her alleged assailant's account. Allison, the Title IX compliance director, responded "that our office can request to be made aware if the Responding Party seeks to re-enroll."

But in August, when Violet's services coordinator asked the EOC to conduct a traffic pattern check, they learned he’d again re-enrolled. The services coordinator raised concerns about the account flag they’d agreed to two months earlier, asking, "If not for my email, would (Violet) have been notified that the Responding Party had re-enrolled?"

Allison told her in an email that “unfortunately, human error prevented that mechanism from being put into place.”

In October 2019, the two met to discuss the EOC’s handling of the investigation. Violet took a recording of the meeting, which she provided to the DTH.

During the meeting, Allison said that flagging an account in this context was new to the EOC, requiring extra steps.

“Those extra steps didn’t happen, to actually have it put into place, because it was going to take more work than our usual process,” Allison said in the recording.

Today, Violet believes the EOC over-promised and under-delivered.

“It was apparent that there was no consistency, and they were getting all of these problems because of that,” Violet said.

When the DTH asked in February how many no-contact orders the EOC issues each year, Allison said the office does not keep that data.

Anna, a UNC graduate whose name has also been changed due to privacy concerns, was granted a no-contact order through the EOC after she reported that a student-athlete sexually assaulted her.

Even after obtaining the no-contact order, Anna said, she still lived in the same residence hall as the alleged assailant. Though no-contact orders prohibit third-party communications, she said his teammates would harass her when their paths crossed.

Anna later dropped her case, telling the DTH that the slow pace of the investigation, the attitude of the investigators and the emotional burden of meeting with her alleged assailant became too much.

In a statement to the DTH on April 28, Allison said the University employs three full-time report and response coordinators in the EOC office who can be expected to respond to reports within 24 hours.

In 2019, the U.S. Department of Education found that UNC had violated the Clery Act, a broad federal campus safety act, many times over nearly a decade. Violations included inadequate systems for sexual violence victims and a lack of administrative capability that “remains a matter of serious concern for the Department.”

Beyond the University

Some students opt not to go through the University for a no-contact order, instead looking to the state. Attorneys and advocates told the DTH that North Carolina’s system could use improvement.

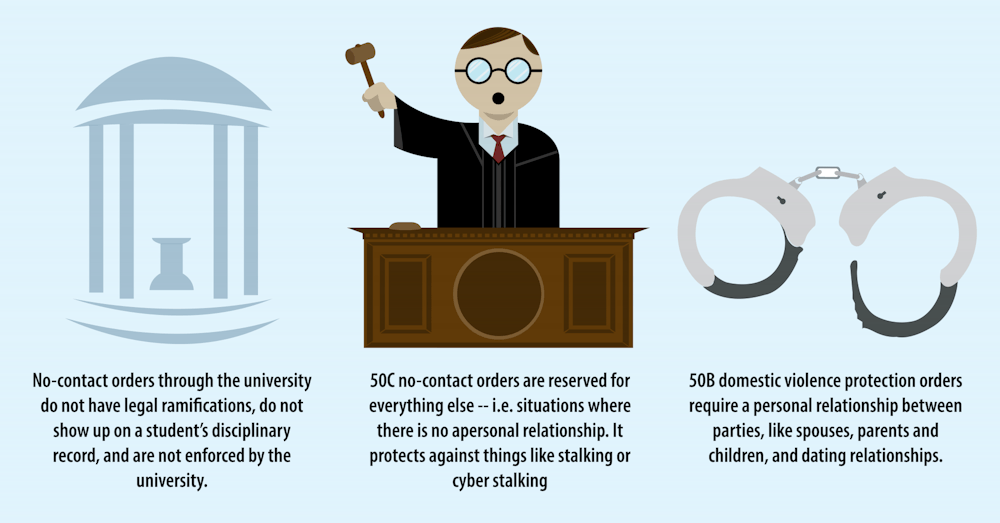

North Carolina’s court system can issue two distinct types of no-contact orders throughout the state. Domestic violence protective orders (50B) and civil no-contact orders (50C) carry different implications.

A 50B is granted when an act of domestic violence occurs between parties in a personal relationship. This includes dating relationships, members of the opposite sex who live together and parent-children relationships. Violating a 50B is a criminal offense in North Carolina.

For parties that don’t meet the statute's personal relationship standard, the 50C order comes into play. These orders are specifically intended for victims of stalking or non-consensual sexual behavior from an offender they don't have a "personal relationship" with.

But 50C violations sometimes result in no more than "a slap on the wrist," said Emma Halker, a hotline advocate with the Compass Center for Women and Families.

Unlike a 50C, if a law enforcement officer sees a 50B violation, they can charge the defendant with or without the victim's cooperation, said Melissa Averett, managing attorney at Averett Family Law in Chapel Hill.

A judge can prescribe different protections under 50B orders because familial or personal relationships imply higher stakes for victims, UNC School of Government professor Cheryl Howell said.

If a victim with a 50C believes it has been violated, they must go back to civil court themselves and request that a judge hold the offender in contempt of court.

“That’s why a lot of times, people just aren’t really scared of 50Cs, because there’s no legal consequence like there would be for a 50B,” Halker said.

But even with a 50B violation, if the victim calls the police for a violation, they may still have to provide the evidence and testimony necessary for a conviction themselves, Howell said.

One UNC student, who was also granted anonymity due to privacy concerns, obtained a temporary no-contact order against another UNC student from an Orange County court during summer 2019. She obtained the order because she alleged he had repeatedly stalked her on campus and in her residence hall.

But before she sought help from the state justice system, the student contacted UNC’s Title IX office. She received an automated response from a coordinator stating she would be out of the office until two days later. The response stated she would still be responding to emails but with a delay.

Three days after the student sent her email, she filed a police report alleging a new incident had occurred.

The following Monday, the student obtained a temporary restraining order from an Orange County court in the form of a civil no-contact order, or a 50C, which she provided a copy of to the DTH. It includes a notice to the defendant asserting that knowingly violating the order “may result in a fine or imprisonment.”

The student heard back from the Title IX office a week after her initial email. The coordinator responded thanking the student for her patience, and encouraged her to continue sharing updates.

"At this time, we are continuing to assess your concerns and consider how University policy might apply, as well as other opportunities for protective measures," the coordinator wrote.

If UNC has no involvement in events related to a no-contact order issued by a state court, the University isn't obligated to help enforce the order, Howell said.

Allison told the DTH on April 28 that while the EOC office doesn’t enforce state-issued no-contact orders, students and employees can contact UNC Police to discuss enforcement. UNC Police officers are sworn officers of the state.

Howell said some prosecutors have developed ways to prosecute domestic violence crimes without the victim's presence, because having to revisit a traumatic situation can be harmful.

“It can be so hard for the victims who are in a personal relationship to pursue any of this,” Averett said.

@seaynthia

@molly_weisner

special.projects@dailytarheel.com