On Feb. 12, the $2.5 million settlement was dismissed by Judge Allen Baddour, who stated the SCV did not have a sufficient legal claim to the monument.

In a statement that night, Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz said he stood by his position that the monument shouldn’t return to campus.

UNC professor William Sturkey said the BOG has handled the situation “about as poorly as they possibly could have."

“They’re just playing politics trying to appease everyone, and it’s just been a disaster for three consecutive years here,” Sturkey said.

Carol Folt

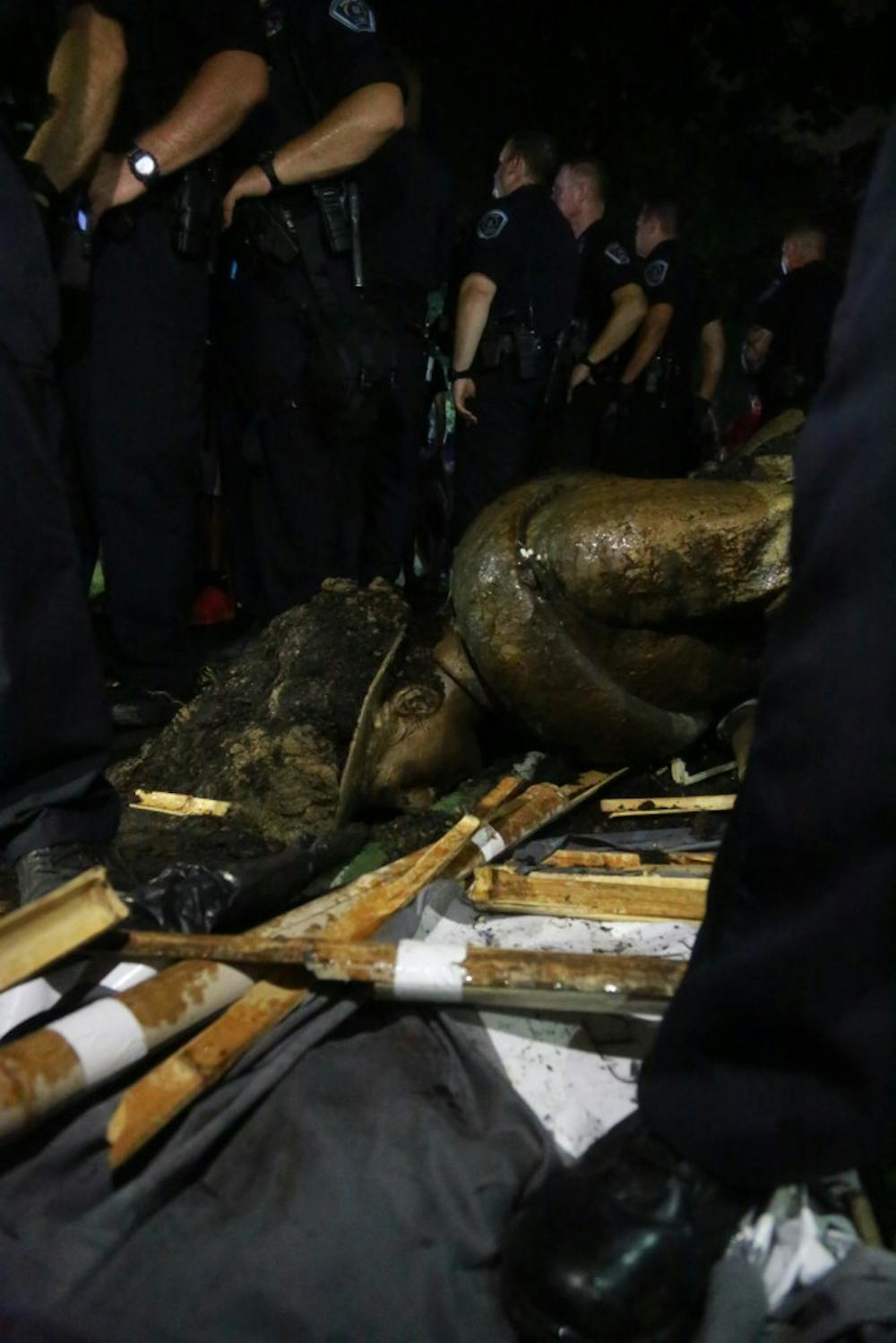

After six years as UNC’s 11th Chancellor, Folt announced in January 2019 that she would resign at the end of the academic year. Within the announcement of her departure, Folt also authorized the removal of the then-empty base of Silent Sam statue from McCorkle Place.

Drafts of resignation letters obtained by The Daily Tar Heel in April 2019 revealed Folt's views on Silent Sam were stronger than what she presented publicly.

The BOG was unaware of Folt's decision to resign prior to her announcement, according to a statement released by the Board.

"We are incredibly disappointed at this intentional action,” the statement said. “It lacks transparency and it undermines and insults the Board’s goal to operate with class and dignity.”

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

Soon after, the BOG voted to move Folt’s last day up to Jan. 31. Following the announcement, Folt said in a campuswide message that though she was disappointed by the BOG’s timeline, she’d “truly loved (her) almost six years at Carolina.”

Less than two months after her departure from UNC, Folt was selected and approved as the University of Southern California's new president on March 20, 2019, after a seven-month search process. She is USC's first female president.

Clery Act violations

On. Nov. 18, then-interim Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz sent a campuswide email sharing the findings of a U.S. Department of Education investigation that reported UNC was operating in violation of the Clery Act, a law that requires colleges and universities receiving federal funding to report on-campus crime statistics and school safety policies.

The final report, released by the Department of Education’s Clery Act Compliance Division, was based on nine findings initially identified in 2017 that detailed the University’s violations, including but not limited to:

- Lack of Administrative Capability

- Failure to Issue Timely Warnings

- Failure to Properly Compile and Disclose Crime Statistics

- Failure to Collect Campus Crime Information from All Required Sources

- Failure to Follow Institutional Policy in a Case of an Alleged Sex Offense

The investigation began in April 2013 after four UNC students, including then-sophomore Landen Gambill, and a former administrator, Melinda Manning, filed a federal complaint against the University regarding UNC’s handling of sexual assault claims that year.

S. Daniel Carter, president of Safety Advisors for Educational Campuses, told the DTH in November that these violations likely indicate UNC hasn’t provided entirely accurate information about crime statistics and campus safety information for decades.

“Clery Act findings, especially this severe, are rare, with only an average of about six findings per year since enforcement began in 1996,” Carter said at the time.

In March, Guskiewicz told the DTH there hadn’t been any fines levied or actions taken against the University in response to its violations. He said discussions between the Department of Education and Office of University Counsel were taking place, and there would probably be updates in the next few months.

Guskiewicz’s appointment and COVID-19 response

Following former Chancellor Folt’s Jan. 31 resignation, UNC System interim President Bill Roper announced Kevin Guskiewicz as interim chancellor on Feb. 6, 2019.

Guskiewicz’s appointment was criticized by some student activists for his communication with students during a fall 2018 teacher assistant strike, when he was dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.

Nearly a year after stepping into his interim role, Guskiewicz was named UNC's 12th chancellor at a Dec. 13 BOG meeting. In the months since, the University has faced controversy over the $2.5 million Silent Sam settlement, Clery Act violations and plans to return to campus in the fall amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

In May, Guskiewicz announced the “Carolina Roadmap,” a plan for how UNC would reopen in the fall.

Faculty and graduate workers have created multiple petitions reflecting their concerns about reopening campus since the announcement.

Rising senior Hanna Wondmagegn said she knows it’s a complicated decision, as the school has financial incentives to remain open. Some students rely on the University’s campus for safe housing, and remote learning can be emotionally draining, she said. Still, she thinks UNC’s current plan is “an invitation to disaster.”

“It's also really important to note whose voices are being left out of the decision-making processes and conversations at a higher level,” she said, referring to faculty, staff, at-risk students and BIPOC students.

“As a Black student myself, I've questioned how enforcement of guidelines and wearing masks is going to happen,” she said. “I also know from experiences and events on campus which groups, communities and areas on campus are more targeted and policed, and which groups, communities and areas on campus are allowed to continue to break the rules without significant consequences.”

While addressing the pandemic, protests over racial and social injustice following George Floyd’s murder have erupted across the country. At the time of publication, Guskiewicz had sent two campuswide messages about the movement, stating a commitment to inclusivity and campuswide dialogue and healing.

“We acknowledge that Carolina has moved too slowly to enact change throughout its history,” Guskiewicz wrote in a June 11 message. “We haven’t done enough to align our actions with our aspirations to be a fully inclusive campus community. While we must continue to listen and learn, we must also move forward with a greater sense of urgency, purpose and action, starting today.”

Some faculty and students have called for action, including defunding UNC Police, an acknowledgement of UNC’s racist history and an end to the previous 16-year moratorium on renaming buildings. UNC BOT voted to lift the moratorium June 17, but Chairperson Richard Stevens said they have yet to consider which buildings will be renamed or options for renaming structures.

Sturkey said even before events of the past month, many people have wanted to see UNC take a stand regarding the history of race in this region and the role the University has played in that history.

“UNC can’t even acknowledge its own history in a public, reparative way. And it can’t make any sort of a moral judgment — your statements against racism fall flat when you have a building named for a Klansman that you refuse to even consider to rename,” he said. “It’s just completely empty so long as we can’t even do very basic tasks in our own community.”

@HannerMcClellan

university@dailytarheel.com